Norman Borlaug, who was born on a farm in Iowa 110 years ago this week, is reckoned to have saved more lives than any man in human history — certainly hundreds of millions, perhaps even a billion. Over the course of his long life (he died at 95 in 2009) he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the National Medal of Science, the Congressional Gold Medal, and Mexico's highest civilian honor. Numerous universities conferred honorary degrees upon him. A statue of Borlaug stands in the US Capitol; there is another in New Delhi, India.

Yet were you to stop 1,000 people at random on the street and ask them about Borlaug, odds are 998 of them wouldn't know his name.

Borlaug was the father of what came to be called the Green Revolution. He went to the University of Minnesota in the 1930s to study forestry, but those plans changed because of a lecture he attended in 1937. The lecturer was plant pathologist Elvin Charles Stakman, and his topic was the fungus varieties known as rust — or, as Stakman called them, "The Shifty Little Enemies that Destroy our Food Crops." Borlaug, a onetime team leader in the Civilian Conservation Corps, had worked with young men who were malnourished because they had no money for food and their visible hunger, as he later said, "left scars on me." Stakman's lecture galvanized in Borlaug's mind the idea of combating hunger by defeating plant diseases. He abandoned his plan to pursue a career in forestry and enrolled instead in the university's plant pathology program, earning a PhD in 1942.

Doctorate in hand, Borlaug first went to work as a microbiologist for DuPont. When his lab was converted to focus on wartime research for the US military, he jumped to the Rockefeller Foundation, which was active in efforts to boost wheat production in Mexico. Moving his family to Mexico City, Borlaug went to war against those "shifty little enemies" — the different forms of rust fungus that kept ruining Mexican crops. He and his team of researchers embarked on a marathon of agricultural experimentation, crossbreeding more than 6,000 varieties of wheat over the course of a decade. He developed a technique called "shuttle breeding" that made it possible for the first time to grow and harvest more than one crop per year. Eventually he hit upon the crucial insight that unleashed the Green Revolution.

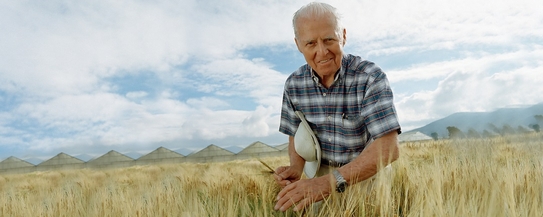

Through years of scientific experimentation, Norman Borlaug perfected grain cultivation techniques that vastly increased the planet's food production. |

That insight was to breed tall tropical wheat varieties, which responded well to chemical fertilizer but tended to fall over from the weight of their seed heads, with short-stalked "dwarf" wheat sturdy enough to support the large and heavy kernels Borlaug's improved strains were producing. The results were phenomenal: Wheat output could be tripled or even quadrupled without needing to plow more land. Within a few years of adopting Borlaug's methods, Mexico had achieved self-sufficiency in wheat. By 1963, Mexico's wheat output was so abundant — nearly six times what it had been when he first arrived — that the country was exporting grain abroad.

Building on his remarkable success in Mexico, Borlaug turned to the Asian subcontinent, where growth in population was far outstripping food production and there seemed to be no way to avoid widespread starvation. Yet what Borlaug's methods had accomplished in Mexico, they accomplished on an even greater scale in India and Pakistan. "The Indian wheat crop of 1968 was so bountiful," The New York Times observed, "that the government had to turn schools into temporary granaries." By 1970, India was producing 20 million tons of wheat, up from 12.3 million just five years earlier. The 2024 harvest is estimated at more than 110 million tons.

"This extraordinary transformation of Asian agriculture in the 1960s and 1970s nearly banished famine from the entire continent," writes Alexander C.R. Hammond in a new book, "Heroes of Progress: 65 People Who Changed the World." "Today, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than population growth, and both countries produce about seven times more wheat than they did in 1965." Borlaug's innovations didn't just preserve human lives on a vast scale, they preserved wilderness as well. Hammond notes that the use of high-yield farming in India kept roughly 100 million acres of wilderness, an area roughly the size of California, from being converted into farmland.

Like most visionaries, Borlaug was plagued by critics and naysayers. It is often the case that those who can, do, while those who can't, write passionate manifestos explaining why it's impossible. "The battle to feed all of humanity is over," doomsayer Paul Ehrlich proclaimed in "The Population Bomb," his fearmongering 1968 bestseller. Hundreds of millions of people were going to starve to death, Ehrlich warned, and there was nothing anyone could do to prevent it.

"He was one of the worst critics we had," Borlaug recalled in a 2000 interview with science writer Ronald Bailey. "He said, 'You aren't going to make any major impact on producing the food that's needed.'" Such relentless pessimism might have been comical if it hadn't been so influential. Under pressure, some of Borlaug's funders backed away. Environmental critics faulted his embrace of chemical fertilizers or genetic modification. Others accused him of failing to respect the earth's natural constraints on food production.

Borlaug was never dissuaded by such censure. The complaints of his well-fed Western detractors would vanish, he said, were they to live for just one month — as he had for 50 years — among the world's poorest people. Man may not live by bread alone, but he has no hope of living without it. Borlaug devoted his years to ensuring that humankind need never lack for bread. He did so not by establishing sweeping social-welfare programs to hand out loaves, but by working tirelessly to develop better strains of wheat, then teaching farmers to grow it. The father of the Green Revolution did something greater than feed people: He enabled them to feed themselves. On the 110th anniversary of his birth, Norman Borlaug's name may be unknown to most of the public. But few Americans achieved so much.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The man in the iron lung

A different kind of American hero died this month in Dallas at 78. I'd never heard of Paul Alexander until I came across his obituary. Now I can't get him out of my mind.

In 1952, when he was 6, Alexander contracted polio. He was playing outdoors when he suddenly felt very unwell. His head ached, his temperature spiked, and as soon as his mother saw him she had a terrible premonition that he had been attacked by the polio virus that was then spreading in a major outbreak, infecting tens of thousands of victims, mostly children. Yet Alexander's parents were told at first to keep their son at home, precisely because the hospital wards were filled with polio patients and the disease was so contagious. Within a few days, however, his small body was almost completely paralyzed; when he could no longer speak or swallow and was struggling to breathe, his parents rushed him to Parkland Hospital. An emergency tracheotomy saved his life. But that life would never be the same.

When Alexander woke up he was encased from the neck down in an iron lung, essentially a metal container that mechanically compressed and inflated his lungs. He was in a hospital ward filled with young people in the same predicament. Patients commonly spent a few weeks in the machine, lying on their backs while recovering from the disease. But Alexander was one of the unlucky victims of polio whose chest muscles were left permanently paralyzed, meaning that they would never be able to breathe normally. Eighteen months after he was admitted, he was discharged and taken home. Doctors warned his parents that their son was unlikely to survive for long. He survived for the next 72 years, spending the vast majority of that time encased in the iron lung.

The emergency polio ward at the former Haynes Memorial Hospital in Boston on Aug. 16, 1955. The city's polio epidemic hit a high of 480 cases and patients were lined up close together in iron lung respirators. Later that year, Dr. Jonas Salk discovered the vaccine that would eradicate polio as a fearsome public health threat. |

Of all the health calamities that can strike a person, none fills me with more dread than the thought of being paralyzed in some way — deprived of the ability to stand, walk, turn, speak, or perform any of the thousand and one functions that able-bodied people take for granted. I cannot imagine coping with the psychological horror of being trapped inside a nonresponsive body; it seems to me akin to being buried alive. I marvel at people who can not only endure such a neurological breakdown without being crushed by despair and fear, but who succeed in living productive, meaningful, even brilliant lives.

Alexander was one of those people.

A physical therapist explained to him that it was possible to master a new way of breathing, one requiring him to gulp and trap air in his throat. If he could master it, he was told, he would be able to leave the iron lung for a few minutes at a time — and as an incentive, he was promised he could have a dog if he succeeded. It took Alexander a year of practice, but he eventually got the hang of what he called "frog-breathing" and was rewarded with a puppy, which he named Ginger.

His ability to "frog-breathe" gradually improved over time. Eventually he could sustain the effort for a few hours, though he could never be away from the iron lung for too long and had to be encased in it when he slept. It was under those circumstances that he grew to adolescence, then adulthood. Tutored by his mother, he was able to complete his education, graduating second in his class from a Dallas high school. He earned a college degree from Southern Methodist University, and then attended law school at the University of Texas in Austin. To write, he had to hold a pen in his mouth and peck out letters on a machine. None of that kept him from passing his courses, getting admitted to the bar, and building a successful family law and bankruptcy practice.

Being imprisoned in an iron lung didn't sever Alexander's connection to the world and to other people. In 2020, he published a memoir, "Three Minutes for a Dog," that had taken him five years to write by mouth, one painstaking letter at a time. During the last year of his life, he developed a following on social media, accumulating more than 400,000 followers on TikTok, where his handle was @IronLungMan and his upbeat messages were viewed millions of times.

Given such phenomenal inner strength, optimism, and drive, what might Alexander have done with his life if polio hadn't locked him in an iron tube? How high might he have climbed? How far might he have traveled? I doubt I would have the spiritual and emotional stamina to surmount the misery of such an existence. Would you? "It's lonely," he conceded in one of his TikTok videos. "Sometimes it's desperate because I can't touch someone, my hands don't move, and no one touches me except in rare occasions, which I cherish."

For all that, he said, "Life is such an extraordinary thing. Just hold on. It's going to get better." RIP.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "Return these exiles to Greece," April 1, 1999:

ATHENS — The year is 1821. Greeks are fighting for their independence. In Athens, they besiege the Acropolis, a stronghold of the Turkish occupiers. As the siege grinds on, the Turks' ammunition runs short. They begin to dismantle sections of the Parthenon, prying out the 2,300-year-old lead clamps and melting them down for bullets. The Greek fighters, horrified at this defacement of their patrimony, send the Turks a supply of bullets. Better to arm their foes, they decide, than to let the ancient temple come to harm.

It is an extraordinary and unexampled gesture of self-sacrifice. But then, the Parthenon is an extraordinary and unexampled masterpiece of Western culture. Built in the 5th century BCE as a shrine to Athena, goddess of war and patron of Athens, it is the acme of classical Greek architecture and sculpture, the greatest monument of the Age of Pericles. There is no more storied building in all of Europe. No Greek could see it vandalized and fail to protest.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"Then we shall all, philosophers, scientists, and just ordinary people, be able to take part in the discussion of the question of why it is that we and the universe exist. If we find the answer to that, it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason — for then we would know the mind of God." — Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time (1998)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.