I HAVE followed John Kerry's career for 40 years, but I still cringe at things that come out of his mouth. Last Tuesday, while preparing to step down as the Biden administration's climate envoy, Kerry told journalists that people would "feel better" about Vladimir Putin's savage and bloody invasion of Ukraine if only Russia would lower its carbon-dioxide emissions.

No, seriously. He really said that. The 31,000 Ukrainian soldiers and 11,000 civilians killed; the deliberate bombing of Ukrainian hospitals, schools, and apartment buildings; the corpses strewn in the streets and stuffed into mass graves in Bucha; the veiled threat to resort to nuclear war if the West keeps supporting Ukraine — Kerry is sure they would all trouble the world less if only the Kremlin put more effort into combating climate change.

"If Russia wanted to show good faith, they could go out and announce what their reductions are going to be and make a greater effort to reduce emissions," Kerry said at the Foreign Press Center in Washington. "Maybe that would open up the door for people to feel better about what Russia is choosing to do at this point in time."

In the World According to Kerry, it's only right that dictators who attack their neighbors and spill vast amounts of blood should at least be more forthcoming on carbon dioxide.

"I mean, if Russia has the ability to wage a war illegally and invade another country," he said, "they ought to be able to find the effort to be responsible on the climate issue." Just in case the obtuseness of his comments wasn't quite clear, he emphasized that Russia's "unprovoked, illegal war" has "sadly" made it impossible to be "engaged in discussions" with Moscow about the climate agenda.

Outgoing climate envoy John Kerry, addressing journalists in Washington, said lower emissions from Russia would make the world 'feel better' about Moscow's invasion of Ukraine. |

Kerry's moral compass has always been awry. When Putin first unleashed his war to conquer Ukraine in 2022, Kerry told an interviewer that one of the worst things about the invasion was that "it could have a profound negative impact on the climate" by generating higher CO2 emissions and — "equally importantly" — by distracting governments from climate change. "You're going to lose people's focus," he lamented. "You're going to lose certainly big country attention because they will be diverted."

It would be charitable to attribute Kerry's tone-deaf comments to age. The former Massachusetts senator, secretary of state, and presidential nominee is 80 years old and perhaps doesn't grasp the impact such words are likely to have. But even in his prime, Kerry was never terribly dismayed about human rights abuses and was always sure the world's worst butchers were people he could reach an understanding with.

During his run for the White House in 2004, The Washington Post reported after interviewing him that "as president he would play down the promotion of democracy" because other issues "trumped human rights concerns in those nations." It is a longstanding pattern.

"Again and again, Kerry has shown a remarkable indulgence toward the world's thugs and totalitarians," I wrote in 2012 when he was nominated to be Barack Obama's second secretary of state.

Within months of becoming a senator in 1985, he flew to Nicaragua in a show of support for Marxist strongman Daniel Ortega, a Soviet/Cuban ally; he returned to Washington talking up the Sandinistas' "good faith." More recently Kerry earned a reputation as Bashar Assad's best friend in Congress. Against all evidence, Kerry described himself as "very, very encouraged" by the Syrian dictator's openness to reform; he repeatedly flew to Damascus to visit Assad, describing him afterward as "my dear friend" and assuring audiences that engagement was working: "Syria will move; Syria will change as it embraces a legitimate relationship with the United States." By the time Kerry finally changed his tune, thousands of Syrian protesters were dead or behind bars.

Just as Russia's scorched-earth assault on Ukraine doesn't seem to upset Kerry nearly as much as its climate record, Iran's record of fomenting horrific terrorist attacks always took second place in his mind to negotiating a nuclear weapons accord with the regime in Tehran. To achieve such a deal, he strenuously advocated lifting sanctions on Iran, even though he presumed that some of the $100 billion the ayatollahs stood to gain would go to pay for more terror. "Sure, something may go additionally somewhere," he serenely told the BBC. But he was sure it would be worth the risk.

In 2015, then-secretary of state Kerry presided over the restoration of diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba; he flew to Havana for the raising of the US flag over the new American embassy. True to form, Kerry was so eager to be ingratiating toward the island's totalitarian government that he purposely snubbed the pro-democracy dissidents who, as The Washington Post editorialized, "embody the values that the American flag represents" — human dignity, individual liberty, and the rights of free expression and assembly.

"The dissidents in Cuba who have fought tirelessly for democracy and human rights, and who continue to suffer regular beatings and arrests will not be witnesses to the flag-raising," the Post noted. "They were not invited."

When Kerry became President Biden's climate envoy, his indifference to human suffering caused by tyrants persisted. With a Bloomberg reporter in 2021, he was glad to discuss at length and with passion what China could do to reduce its reliance on coal. But then the reporter raised the matter of solar panels manufactured in China by enslaved Uighur Muslims. "What is the process," he asked, "by which one trades off climate against human rights?"

Kerry's answer, as usual, was to downplay human rights. "Life is always full of tough choices," he said cavalierly. "Yes, we have issues.... But first and foremost, this planet must be protected." He didn't mean protected from slavery and despotism. Again and again he has made his position clear: What he calls our "differences on human rights" with the world's worst dictators should not be allowed to "get in the way" of signing diplomatic deals on climate or nuclear weapons.

So when Kerry told his audience last week that the world would "feel better" about the slaughter and devastation in Ukraine if only Russia would bring its emissions down, he wasn't speaking with the wandering carelessness of an old man. He was being himself. The most brutal and murderous land war in Europe since World War II, in which tens of thousands of people have been killed? That might upset some people, but Kerry isn't among them.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

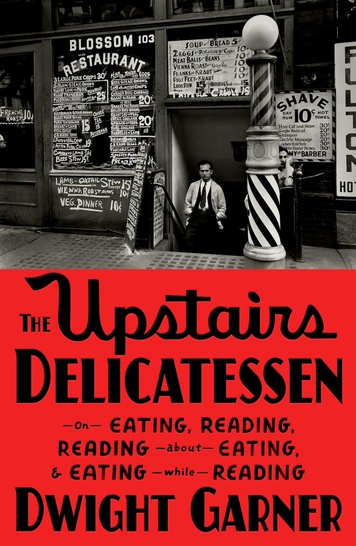

'The Upstairs Delicatessen'

When I was first getting to know my future wife, it perplexed me that when she ate, even if she were eating alone, the only thing she did was — eat. Whether her meal was a sandwich or a four-course dinner, she gave it her full, undistracted attention. I was never like that. When I ate, I wanted to read. As a kid, having cereal and milk for breakfast with my siblings, I would claim the cereal box that had the most text printed on it, so I could consume the words while I consumed the Alpha-Bits. As an adult, if I'm eating alone I am simultaneously working my way through a newspaper or three, or reading a magazine, or turning the pages of a current book — anything to keep my eyes from going hungry.

Dwight Garner, the influential New York Times book critic, is another eater-who-reads and reader-who-eats. But he has developed those skills/appetites/cravings to an intensity I could never have imagined before discovering "The Upstairs Delicatessen," his scrumptious new book on the interlaced delights of voracious eating and reading.

A new book celebrates the twin joys of eating while reading and reading about eating. |

Garner seems to remember every meal he has ever eaten, from the working-class suppers he grew up with in West Virginia ("sauerkraut with sliced-up franks; spaghetti with fried ground hamburger") to the avant-garde gastronomical concept foods he has eaten at the tables of high-tech foodies on the coasts ("a cluster of pressure-cooked mustard seeds with squid ink"). He also seems to remember every quotable reference to food and drink in every novel, memoir, and even poem he has ever read. Describing himself as "an omnidirectionally hungry human being," he merrily conveys his own perceptions of foods he has eaten — and conveys with even greater pleasure the perceptions of other writers.

Here he is, for example, beginning his discussion of eggs in his chapter on breakfast:

I cook two eggs almost every morning. The results often belong in the Hall of Fame. On gray days when I overcook them, they still belong in the Hall of Very Good. I confessed my daily egg habit in the Times and received several emails warning me of myocardial infarction. I have a hard time abstaining. So did Henry James, who wrote in "A Little Tour in France," "I am ashamed to say how many of them I consumed." James Bond, in Ian Fleming's novels, eats scrambled eggs like a maniac. So well-known was Bond's penchant for eggs that a proofreader of Fleming's novel "Live and Let Die" noted "the security risk this posed to Bond, writing that whoever was following him need only walk into a restaurant and ask, 'Was there a man here eating scrambled eggs?'"

In the same chapter, Garner writes about Quaker Oats and about toast, about tea and about coffee, about the breakfast scene in Stanley Tucci's movie "Big Night" and about the power of bacon to convert vegetarians back to carnivorism, about how seriously Southerners take their biscuits and even about the foods he doesn't want to see in the morning:

Claire Tomalin, a biographer of Thomas Hardy, wrote that his favorite breakfast was "kettle-broth:" "chopped parsley, onions, and bread cooked in hot water." In a diary entry from 1983, Richard Burton wrote about Elizabeth Taylor, "She stinks of garlic — who has garlic for breakfast?" Vladimir Nabokov was asked about moments from the past he wished had been captured on film. He replied: "Herman Melville at breakfast, feeding a sardine to his cat."

Other chapters revolve around lunch, grocery shopping, drinking, and dinner, plus an "interlude" that diverges into napping and swimming. All of it is suffused with a joyous lack of pretension. Garner doesn't just take pleasure in eating, drinking, and reading, he cannot wait to share the experience with the rest of us. The writers he admires most are those "who wrote about people who liked to tuck into life," a category that plainly includes Garner himself.

I have never read a book like "The Upstairs Delicatessen." It is eccentric, funny, savory, elegant, profane, and wildly entertaining. I must see if I can get my wife to read it while she eats.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

Not your typical column

To mark my (first) 30 years on the Op-Ed page, this year I will occasionally resurrect a column that I wrote about something far off the beaten path — an idiosyncratic topic that no one was expecting at the time and that I've never written about since.

Here is a column I wrote in 1998 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of George Gershwin.

"Still we sing: 'S wonderful! 'S marvelous!" Sept. 24, 1998:

HE PUBLISHED his first song in 1916, when he was 17 years old. He died 2½ months before his 39th birthday. In that short interval, George Gershwin created some of the most essential music of the 20th century. He wrote for Tin Pan Alley and for the New York Philharmonic, for Broadway and for Hollywood. No less highbrow an authority than Arnold Schoenberg said of him, "I know he is an artist and a composer; he expressed musical ideas, and they were new." And no less legendary a tunesmith than Irving Berlin declared, "We were all pretty good songwriters. But Gershwin was something else. He was a composer."

In his own lifetime he was hugely popular. Sixty years after his death he is even more beloved. Dozens of his songs are standards now, endlessly reinterpreted by singers sublime (Ella Fitzgerald) and ridiculous (Twiggy). He was a high school dropout; his neighbors never expected him to amount to much. But the immigrants' kid from the Brooklyn tenements turned out to be one of the giants of American musical history.

They all laughed at Christopher Columbus

When he said the world was round;

They all laughed when Edison recorded sound.

They all laughed at Wilbur and his brother

When they said that they could fly.They told Marconi

Wireless was a phony

It's the same old cry. . .The lyrics were by his older brother Ira. It was for Ira that Morris and Rose Gershvin (as the surname originally was) bought a piano, but it was George, then 12, who monopolized it. Two years later, piano lessons began; the year after that, he was working for Jerome H. Remick & Co., a music publisher, as the youngest piano pounder in Tin Pan Alley. "He played all day," Ira wrote, "traveled to nearby cities to accompany the song pluggers, was sent to vaudeville houses to report which acts were using Remick songs, and wrote a tune now and then...."

His first hit came in 1919, when Al Jolson sang "Swanee," a number Gershwin had written with lyricist Irving Caesar. It became the biggest hit of his lifetime. Jolson's recording sold more than 2.5 million copies, a mind-boggling number for an age when phonograph music was still in its childhood.

"Swanee" was only the start. Gershwin wrote something on the order of 1,000 songs, most of them for Broadway musicals now forgotten. Few remember the 1924 show "Lady Be Good," but the title song is immortal. So is "The Man I Love." We take it all for granted now, but 70 years ago Gershwin's musical language was new and aggressive. These were no mannered operettas he and his brother were writing. They were jazzy, driving, angular — very American, very 1920s.

Fascinating rhythm,

You've got me on the go,

Fascinating rhythm,

I'm all a-quiver!What a mess you're making!

The neighbors want to know

Why I'm always shaking

Just like a flivver."Strike Up The Band." "Someone To Watch Over Me." "How Long Has This Been Going On." "I've Got A Crush On You." "Let's Call The Whole Thing Off." "'S Wonderful." "Summertime." It is impossible to imagine the American songbook without Gershwin. And if he hadn't died so long before his time, how many more melodies would have flowed from that remarkable pen?

His popular music alone would have guaranteed Gershwin fame everlasting. But from the start he was equally interested in writing "serious" music. In 1924, Paul Whiteman invited him to contribute a piece of music to a concert he was organizing on the theme of "What Is American Music?" Gershwin was just wrapping up the score for a new musical, and it wasn't until he was headed to Boston for the pre-Broadway tryout that he began to focus on Whiteman's commission. On that journey, "Rhapsody in Blue" was born.

"It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty-bang that is often so stimulating to a composer that I suddenly heard — and even saw on paper — the complete construction of the Rhapsody, from beginning to end," he later recalled. "I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America."

There had never been anything like "Rhapsody in Blue," with its fabulous glissando clarinet opening. In 1928, "An American in Paris" premiered at Carnegie Hall, and there had never been anything like that, either, with its bluesy themes and scoring for taxi horns. And it goes without saying that "Porgy and Bess," Gershwin's 1935 masterpiece, was something astonishingly new under the sun. The reviews were unfriendly, and the show closed after just 124 performances. But Gershwin always knew it was his greatest creation. Today is there anyone who doesn't know?

In time the Rockies may crumble, Gibraltar may tumble. But Gershwin's music? It's here to stay.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"But in the world according to Garp, we are all terminal cases." — John Irving, The World According to Garp (1978)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.