With 466 physicians for every 100,000 residents, Massachusetts has by far the highest ratio of doctors to population of any state in the union. Given such an abundance of medical talent, patients in the Bay State ought to have some of the shortest wait times in America to see a physician.

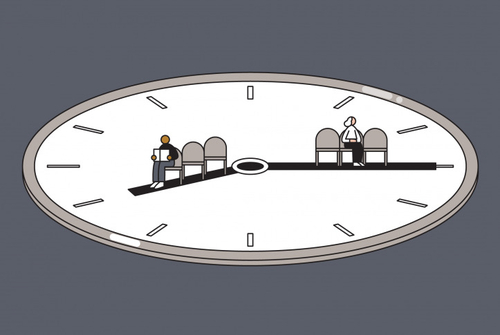

But as countless Massachusetts residents can attest, that isn't the case. The Commonwealth may be a health care mecca, but accessing that care is often a frustrating exercise in waiting . . . and waiting . . . and waiting. In its 2022 Survey of Physician Appointment Wait Times, the physician search firm Merritt Hawkins found that getting an appointment to see a doctor takes longer in the Boston area than in all but one of the 15 major metropolitan areas it examined. (Only in Portland, Ore., are wait times longer than in Boston.) To see a cardiologist in Boston requires waiting an average of 29 days; for an obstetrics-gynecology appointment, the average delay is 35 days; for family medicine, 40 days; for dermatology, 50 days.

Why such long wait times? Merritt Hawkins cites a slew of potential explanations, including patient demographics, disease incidence, income levels, lifestyle choices, rates of insurance coverage, and physician practice patterns. The backlog caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, when a large share of the public was forced to postpone or go without many kinds of medical care, exacerbated the bottleneck.

Meanwhile, writes Oliver Kharraz, a physician and founder of the digital health marketplace Zocdoc, while demand for care is rising, the supply is contracting. "Staffing shortages abound," he observed recently in STAT. An estimated one in five health care workers have quit their jobs since 2020 and "in 2021 alone, 117,000 physicians left the workforce while fewer than 40,000 joined it."

Making all these factors worse is the distortion of the health care market caused by our reliance on third-party payers.

Thanks to tax preferences dating back two generations, patients have come to expect most medical treatment and procedures — even routine prescriptions — to be covered by health insurance. Consequently, insurers wield far more economic clout than patients do. Providers — doctors, hospitals, urgent care facilities — are forced to accommodate the demands of insurance companies, since it is they who pay the tab. When patients think someone else is paying most of their health care costs, they feel little pressure to learn what those costs actually are — and providers feel little pressure to compete on price or value. Add to all that the plethora of coverage mandates imposed by state and federal governments, and it is no wonder that health care pressures have grown intolerable. Many medical practices won't take new patients. Result: people can't get the care they want, or can't get it from the providers they prefer, or can't get it without having to hunker down for a long wait.

But there is this consolation, even for those of us who live in Massachusetts: We aren't in Canada.

For reasons I have never been able to understand, Canadians express an abnormal pride in their nation's single-payer health care system. Bizarrely, it is the feature of Canadian life they extol above all others. In a 2019 nationwide survey for the Association for Canadian Studies, a whopping 73 percent of respondents said that their country's publicly funded universal health system was most important to them as a source of personal or collective pride in Canada. It outranked everything else, including the Canadian flag, the national anthem, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the armed forces, the country's bilingualism, and all of Canada's professional sports teams.

And yet, as the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, a Canadian think tank, noted when those results were published, "study after study ranks Canadian health care below" that of most countries in the 38-member Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD. "We outperform many poor, undeveloped nations, but this is surely not a cause for pride."

Another Canadian policy center, the Vancouver-based Fraser Institute, each year releases "Waiting Your Turn," an annual estimate of health care wait times, based on a survey of physicians in 12 medical specialties. In its 2023 report, published this month, the institute found significant variations among provinces and medical fields, but the overall picture was grim: The median wait time in Canada for medically necessary diagnostic or surgical procedures is now 27.7 weeks. Between getting a referral from a primary care physician to getting the necessary treatment, Canadians can expect to wait more than six months. That is the longest gap ever recorded in the survey's history — triple what it was in 1993.

Even procedures as simple as an ultrasound or MRI, something Americans can typically access within days, can take weeks or months to schedule north of the border. In 2023, according to the new report, Canadians were waiting 5.3 weeks for an ultrasound, 6.6 weeks for a CT scan, and 12.9 weeks for an MRI scan.

In the Fraser Institute's words: "Waiting for treatment has become a defining characteristic of Canadian health care." For Americans, thankfully, the picture is not nearly that bleak. But it could come to that. For years, progressive advocates and politicians like Ralph Nader and Bernie Sanders have wanted to remake the American system along Canadian lines. If they prevail, the current waiting game — even in Massachusetts — will be remembered as the good old days. Now we may be waiting, on average, 20 or 30 days to see a specialist or get treatment scheduled. Follow Canada's lead, and we'll be waiting 20 or 30 weeks.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Sharansky's Hanukkah

In his transcendent prison memoir, "Fear No Evil," Natan Sharansky tells the story of his nine years in the Soviet gulag, a fate to which he was sentenced for the crime of wanting to emigrate to Israel. Even now, 35 years after it was published, it is an amazing read, a great narrative by a great man who refused to be intimidated by his captors. The more the KGB tried to berate or punish him for his Jewish pride and Zionist yearning, the more joyfully and fearlessly Sharansky embraced them.

To mark this week of Hanukkah, consider this extraordinary incident recounted in "Fear No Evil."

Sharansky was in the Siberian prison camp of Perm 35 and Hanukkah was drawing near. Intent on observing the holiday as best he could, Sharansky had a menorah constructed from some wooden scraps. A few candles were found, and each evening Sharansky lit his menorah, reciting the blessing, and describing to his fellow prisoners — none of them Jewish — the story of the Maccabee rebellion long ago. On the sixth night of Hanukkah, the authorities confiscated his menorah and candles. When he demanded to know why, a prison guard claimed that the menorah was made from "state materials" and therefore illegal.

Natan Sharansky, a former Soviet prisoner of conscience, at a press conference in 2010. |

Sharansky declared a hunger strike. "In a statement to the procurator general," he recounts, "I protested against the violation of my national and religious rights, and against KGB interference in my personal life."

Two days later, Sharansky was summoned by Major Osin, the prison camp warden. Osin wanted the refusenik to call off his protest before the expected arrival of an inspection committee. In that case, Sharansky said, "Give me back the menorah, as tonight is the last evening of Hanukkah." He promised to end his hunger strike if he was allowed to light the candles.

But a protocol for its confiscation had already been drawn up, and Osin couldn't back down in front of the entire camp. . . . I was seized by an amusing idea.

"Listen," I said, "I'm sure you have the menorah somewhere. It's very important to me to celebrate the last night of Hanukkah. Why not let me do it here and now, together with you. You'll give me the menorah, I'll light the candles and say the prayer, and if all goes well I'll end the hunger strike.

Osin thought it over and promptly the confiscated menorah appeared from his desk.

When Sharansky said he needed eight candles, Osin took a knife and cut the candle into eight stubs. Then, with amazing audacity, Sharansky said that the ceremony required everyone present to stand with head covered, listen to the blessing, and answer "Amen."

Osin complied. He stood behind his desk, donned his major's cap, watched as Sharansky kindled his eight candle stubs, and then waited for his prisoner to recite the blessing. Speaking in Hebrew — which Osin, of course, did not understand — Sharansky recited a blessing he had composed himself: "Blessed are you, O God, for allowing me to light these candles. May you allow me to light the Hanukkah candles many times in your city, Jerusalem, with my wife, Avital, and my family and friends."

Then he had a brainstorm.

Inspired by the sight of Osin standing meekly at attention, I added: "And may the day come when all our enemies, who today are planning our destruction, will stand before us and hear our prayers and say 'Amen.' "

"Amen," Osin echoed back. He sighed with relief, sat down, and removed his hat.

Sharansky writes that he returned to his barracks "in a state of elation." Who can doubt it? What magnificent chutzpah! What a triumph of the spirit! And what an uplifting reminder that even in the depths of the gulag — even in a time and place filled with the enemies of Jewish faith and freedom — those who refuse to fear can turn the table on their oppressors and dispel the darkness with a candle's light.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

On the twelfth . . .

This is the 12th day of the 12th month, so Christmas Eve is 12 days away and will be followed in turn by the 12 days of Christmas. By the time they end, 2023 with all its wickedness will have ended and 2024 begun, and we shall see if "thus the whirligig of time brings in his revenges," as Malvolio says in Shakespeare's "Twelfth Night."

Many numbers have fascinating quirks and quiddities, but 12 has a glamor few numerals can match. As a matter of basic arithmetic, it is the first number that can be evenly divided by 2, 3, 4, and 6. That helps explain why it has long been a favorite quantity in commerce and to this day is standard in packaging everything from eggs to liquor bottles to batteries to soft drinks. Twelve is also the number of lunar cycles in a solar year and consequently the number of sections into which ancient astronomers (or astrologers) divided the sun's apparent path around the Earth each year. The changing groupings of stars and planets visible at different times of the year gave rise to 12 classic constellations and their associated signs of the zodiac.

The 12 days of Christmas are only one example of the number's sacred significance in many cultures. In the Hebrew Bible, the patriarch Jacob has 12 sons, whose descendants become the 12 Tribes of Israel. In Christianity, Jesus' 12 primary disciples are known as the Apostles and the number 12 appears again and again in the New Testament book of Revelation. In the pagan mythology of Greece, there were 12 Olympian gods: Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Hades, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Hermes, Ares, Hephaestus, and Dionysus. And in the largest branch of Shiite Islam, the successors of Muhammad were the 12 Imams.

At his legendary Round Table, King Arthur had 12 knights, including Sir Galahad, Sir Lancelot, and Sir Gawain. In a much earlier legend, Hercules had to perform 12 daunting labors, such as killing the Hydra (with its regenerating serpent heads), cleansing the Augean stables (which were filled with the accumulated dung of 3,000 cattle), and bringing the ferocious three-headed dog Cerberus up from the underworld.

Juries comprise 12 persons, a tradition dating back to at least 1066, when William the Conqueror introduced the practice to England. By the 14th century the practice was standard and English settlers later brought it with them to America. (One of the reasons in the Declaration of Independence for the colonists' rebellion against King George III was his "depriving us, in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury.") It's a good thing that revolution succeeded — otherwise there might never have been a Hollywood to make "12 Angry Men."

Speaking of Hollywood, it has produced other "12" classics, from "The Dirty Dozen" to "Twelve Years a Slave." As a boy, I loved "Cheaper by the Dozen," the based-on-a-true-story novel of Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and their 12 children. And 60 years after it first aired, Rod Serling's Twilight Zone episode "Number 12 Looks Just Like You" — a TV drama in which every adult is expected to submit to surgery to change their physical appearance to match one of several attractive options — remains as dystopian, yet creepily relevant, as ever.

All that doesn't begin to exhaust the power and presence of "12" in our culture. While a pound normally consists of 16 ounces, that changes to 12 for gold, silver, and other precious metals, which are weighed in troy units. There are 12 inches to a foot, 12 steps to the Alcoholics Anonymous program, and 12 black and white keys to an octave on the piano. The classic vinyl LP record has a diameter of 12 inches, the numbers on a clock run from 1 to 12, and students graduate from high school upon completing 12th grade. And on Dec. 14, 1972 — 51 years ago this week — US astronaut Gene Cernan became the last of the 12 men (so far) who have walked on the surface of the moon.

If there were a Hall of Fame for numbers, 12 would be one of the original inductees. There is no such institution, of course. But there is a Pro Football Hall of Fame, to which Tom Brady is certain to be inducted the moment he is eligible. In his 23 seasons as a professional athlete — 20 for the New England Patriots, three for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers — Brady acquired the reputation of the greatest quarterback in NFL history. And he did so, as even non-sports fans like me know, while wearing jersey No. 12.

No ordinary number |

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "The case against censure," Dec. 17, 1998:

What [President] Clinton deserves and what the country needs is not a symbolic rebuke from which he will bounce back unscratched. There is only a momentary sting in being censured; impeachment will sting through history. Clinton has lied and deceived throughout his political climb. It is fitting that his lies and deceit be the cause, finally, of his fall.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"There were three thousand six hundred and fifty-three days like that in his stretch. From the first clang of the rail to the last clang of the rail. The three extra days were for leap years." — Alexander Solzhenitsyn, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.