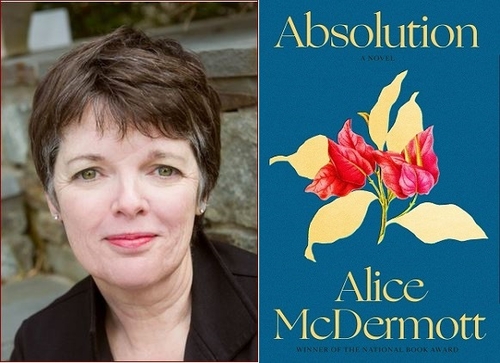

I HAVE READ some compelling fiction set during the Vietnam War, including James Webb's Fields of Fire and Tim O'Brien's Going After Cacciato and The Things They Carried. But no Vietnam book has ever hooked me from its first page like Absolution, a delicate and dazzling new novel by the acclaimed author Alice McDermott.

Most of Absolution is narrated by Patricia, a shy newlywed who has come to Saigon in 1963 with her husband Peter, an engineer and lawyer on loan to US Navy intelligence. As the book opens, Patricia is preparing to attend a cocktail party:

You have no idea what it was like. For us. The women, I mean. The wives.

Most days I would bathe in the morning and then stay in my housecoat until lunch, reading, writing letters home — those fragile, pale blue airmail letters with their complex folds; evidence, I think now, of how exotic distance itself once seemed.

I'd do my nails, compose the charming bread-and-butter notes we were always exchanging — wedding stationery with my still-new initials, real ink, and cunning turns of phrase, bits of French, exclamation marks galore. The fan moving overhead and the heat encroaching even through the slatted blinds of the shaded room, the spice of sandalwood from the joss stick on the dresser. . . .

I was twenty-three then, with a bachelor's from Marymount. For a year before my marriage, I'd taught kindergarten at a parish school in Harlem, but my real vocation in those days, my aspiration, was to be a helpmeet for my husband.

That was the word I used. It was, in fact the word my own father had used, taking both my gloved hands in his as we waited for the wedding guests to file into our church in Yonkers. . . . He said, "Be a helpmeet to your husband. Be the jewel in his crown."

I said, "I will."

McDermott's writing, so graceful and adroit, evokes an era and a mindset all but unimaginable today. America in 1963 was in the early stages of its Vietnam involvement. Deployment to Saigon seemed "a lovely, exotic adventure," where Americans dwelt in a "cocoon" that was "still polished to a high shine by our sense of ourselves and our great, good nation." The reader, of course, knows that in a few years that high shine will fade, the adventure will become a debacle, and America's sense of itself will be battered. But Patricia has no conception of what lies ahead; she seeks only to help her husband as he and the other men go about their work.

Yet those men and that work barely figure in this story. Absolution is a novel about the wives, and above all about Patricia's relationship with Charlene, a cunning, sophisticated, and imperious schemer. The two women meet at the cocktail party, and before long Patricia has been co-opted into Charlene's "cabal" of women who raise money to buy small gifts — candy, crayons, dolls, chocolate — for distribution to Vietnamese children in hospitals and orphanages. Patricia envies Charlene's ability to get other people to do things for her, yet make them feel as though she has done them a favor. Women like Charlene, Patricia observes, are somehow able

to enlist the help of strangers without ever seeming helpless themselves. They got other people to take care of them, to lend them a scarf, or ten dollars, or an umbrella, to hail them a cab or pick up their dry cleaning, and then they made their gratitude seem facetious, as if they had merely accepted your favors in order to allay your anxiety to bestow them.

McDermott excels at drawing out such nuances of character. Charlene can be obnoxious and peremptory — she swears and drinks and pops pills and insists on calling Patricia "Tricia," a name she has never gone by. But it gradually becomes clear that for all her confident, cynical bossiness, Charlene is driven by a genuine urge to do good and capable of great compassion. When Patricia, who yearns to become a mother, has a miscarriage, Charlene reacts with a fierce empathy and improvises a gentle, deeply touching, ceremony to baptize the embryo. But there is nothing gentle or empathetic about the lengths to which she later goes to enable Patricia to achieve motherhood. Charlene is simultaneously driven to be a benefactor to impoverished Vietnamese families and prepared to run roughshod over their autonomy if that's what it takes to get her way. It isn't hard to connect the metaphorical dots that link Charlene's heedless altruism and America's experience in Southeast Asia.

Absolution is Alice McDermott's ninth novel. |

A key theme of the novel is the place of women in American society in the early 1960s. Patricia is in love with her husband and anxious not to do anything that will impede his success or embarrass him. Far from resenting the submissiveness that society expects of young wives toward their husbands, she regards it as normal. Late in the book, Peter decides to quit his job in Vietnam and arranges for them to fly home. Patricia is stung to learn of his decision not from her husband but from Charlene. It was only then, she says, looking back years later, that she "felt, perhaps, the first real sense of humiliation at my own childishness. . . . We'd never discussed it at all. No fault of Peter's really." That is simply "what it was like for us, in those days. Us wives."

There is much more to the novel, which I found irresistible and consumed in a couple of sittings. Frankly, McDermott could write about automotive repair or algebra and her prose would be mesmerizing. Absolution is more than just an elegant and evocative story — it is a story about Vietnam told from a wholly unfamiliar angle, one few other authors could have told so well.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "What real hate speech sounds like," Nov. 2, 1998:

Sixty years ago next Monday, on the night of Luther's birthday, Nazi gangs rampaged across Germany. In every Jewish neighborhood, windows were smashed and buildings were torched. All told, 101 synagogues were destroyed, and nearly 7,500 Jewish-owned businesses were demolished. On that night, 91 Jews were murdered; 26,000 more were rounded up and sent to concentration camps. It was the greatest pogrom in history. And it was nothing compared with what was to come.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"A cold wind rushed up the staircase, and a long loud wail of disappointment and misery from his wife gave him the courage to run down to her side, and then to the gate beyond. The street lamp flickering opposite shone on a quiet and deserted road." — W. W. Jacobs, The Monkey's Paw (1902)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.