The girl who tugged John Silber's ears

From the moment he arrived in Boston, the late Boston University president John R. Silber was a force to be reckoned with. Brilliant, eloquent, volatile, and extraordinarily talented, he was impossible to ignore. On his watch, Boston University was transformed from a flailing mediocrity to a world-class research institution and one of the nation's largest private universities. He was like no academic America's foremost academic city had ever known. He never shied away from controversy, never "spoke plastic," and never sacrificed what he regarded as truth on the altar of political correctness.

For more than three decades, from his hiring as BU's president in 1971 until he retired in 2003, Silber — "a philosopher by training but a fighter by instinct," in The New York Times's characterization — fueled intense passions. He had legions of admirers and legions of critics. He acquired a national reputation but his renown was greatest in Boston — so much so that in 1990 he became the Democratic nominee for governor, a race he narrowly lost (to William Weld) but which only enhanced his reputation for intellectual fierceness. Now, a decade after his death in 2012, there are Boston residents with no memory of the man. But for the better part of 35 years, he was a formidable presence in the life of this city.

Twice I worked for Silber. As a BU law student in the early 1980s I landed a part-time job as a researcher in Silber's office. Several years later, with both law school and my exceedingly brief legal career behind me, I returned for a full-time job with the exalted title of Assistant to the President.

"Having John Silber as a boss, I quickly learned, was an ongoing adventure in being put in one's place," I recounted when he died.

When he was in a temper — and there were times when it seemed to me that he was in a temper five days a week — I dreaded getting the summons: "Dr. Silber would like to see you now." Once, when I emerged from his inner office after a tongue-lashing so forceful it had probably been heard as far away as Nickerson Field, one of his secretaries tried to comfort me.

"He only treats you that way because he regards you so highly," she said. "It's his way of tempering you, like fine steel." I smiled wanly at her attempt to be kind, and went off to lick my wounds.

I stayed in that job for only 16 months, but the memories remain vivid.

At times he treated me as if I were a wunderkind and his protégé. When I first started, Silber ordered that I be given one of the grandest offices in the president's townhouse on Bay State Road, moving the employee already occupying that office to a decidedly inferior space. After a freelance column I had written was published in a leading newspaper, Silber mailed copies to a half-dozen prominent individuals, with a cover letter singing the columnist's praise. When I proposed that BU offer admission to a "refusenik" — a Soviet teenager whose family was being persecuted for wanting to emigrate — Silber did more than greenlight the idea as a way to generate publicity: He directed every relevant university department, from Financial Assistance to the General Counsel, to make a serious effort to get the boy out of the USSR.

But his disdain could be scorching. Once, in front of several senior administrators, he berated me in four-letter words as an incompetent, flinging a wadded-up document at my head as he ordered me out of the room. On another occasion, when I asked if he wanted me to accompany him to a meeting of the Faculty Senate, he informed me, in a tone dripping with scorn, that he was perfectly capable of dealing with the faculty without my assistance.

Sixteen months of that was my limit, but some aides remained with Silber for decades. He inspired intense loyalty in people of tremendous ability. I once asked one of them — a brilliant older man, a gifted writer with an encyclopedic range of knowledge — why he tolerated Silber's rages. "Because," he replied, "John Silber is a great man."

Though hundreds of thousands of words have been written about Silber over the years, a full-scale biography has yet to be produced. But his oldest daughter, Rachel Silber Devlin, has just published a captivating memoir of her father, illuminating a lesser-known side of his life. Snapshots of My Father focuses on John Silber as a family man — husband, father, grandfather. It is filled with a wealth of details and stories that only someone who grew up under Silber's roof could relate.

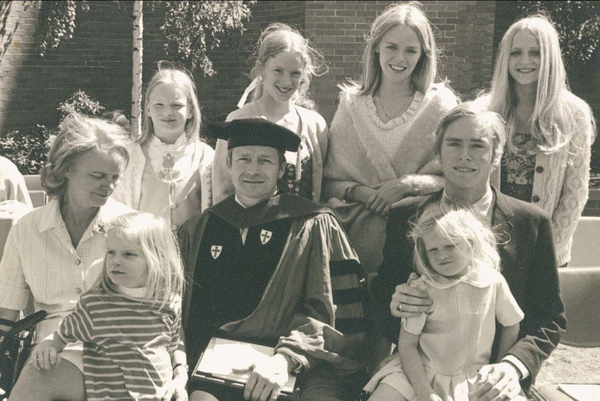

At his first Boston University commencement as president, John Silber was joined by his wife, Kathryn, and their seven children. |

Devlin sketches her father's upbringing in San Antonio and his marriage to Kathryn Underwood, his college debating partner, when they were both just 20. The couple had seven children, a son followed by six daughters, and Devlin describes their upbringing, first in Texas, then Massachusetts. The college president and political candidate who could be so unsparing and relentless in public could also be severe in private. But Silber plainly adored his wife and children, and Devlin's account makes it clear that for all his fierceness, her father had a soft streak.

"When he was laid back and easy, no one was more fun," Devlin writes.

I remember, when I was quite young, regularly holding on to his ears as I stood behind the driver's seat when Pop was at the wheel. I felt like I was involved in the driving decisions. I would tug to the right if we were going right and tug to the left if he turned left. It was like holding the reins of a horse, but even more cozy. . . . Pop loved those physical, emotional connections.

One theme that runs through Devlin's memoir is her father's enthusiasm for socializing, particularly when his family was involved. "Pop loved planning parties and was fastidious in devising every feature," she recalls. One regular event was the Fourth of July get-together, when Silber, manning the grill, liked to barbecue a whole goat. "He also made two kinds of sangria for these parties, one red and one white." They were, she notes, "very high-octane drinks," helping set the stage for the party's climax, when "Pop would crown the evening by firing off some illegal Roman candles and bottle rockets in the street." To those of us who only ever encountered Silber in his professional persona, these vignettes of Silber the merrymaker are, to say the least, eye-opening.

Devlin writes with great poignancy about Silber's bond with her brother David. Like his father, David was deeply interested in art. He had a gift for drawing that Silber was delighted to encourage. During a year the family spent in Germany, where Silber was studying on a Fulbright scholarship, he took his little boy to museums and castles, exposing him to a wide array of art and architecture.

"When we returned to the United States, the mother of the kids next door sent David home because he was drawing pictures of naked women," Devlin relates. "After spending time in museums on our European travels, he was innocently drawing what he had seen. Pop was impassioned in his defense of David and insulted the lady's small-mindedness while he was at it." When, much later, David came out as gay, his father's chief reaction was chagrin that his son would never have children. (Adoption by same-sex couples was unknown then.) "Children were an integral part of Pop's life and he saw the prospect of a childless existence as a bleak landscape," writes Devlin. The saddest passages in the book describe David's death from AIDS at 41, following months of being nursed at home by his parents. During those months, Silber couldn't hide his breaking heart. He grew "halting and inefficient" and would "wander around the house aimlessly," his daughter recounts — a far cry from the sandpapery pugilist that most of the public saw in Silber.

Devlin devotes an entire chapter to her father's temperament. She says she often wondered whether his "explosive temper and his vehement quest for excellence" were a psychological compensation for his notable birth defect — a deformed right arm that ended in a stump just below the elbow. Because of his volcanic temper, she observes perceptively, he often deprived himself of the chance to see people at their best. Too many individuals were unable to be at ease in Silber's presence, either because they were intimidated by his overbearing manner or because his harangues made them resentful and defensive.

For the same reason, she says, he "missed out on a lot of his kids' silliness." If he wasn't in a playful mood, they couldn't be either. They felt constrained to be on their best behavior when he was around, knowing that they weren't exempt from the ferocity he so often deployed against others. "If you were ever on the receiving end of one of those diatribes you would not soon forget it, and you would hold it against him, however charming he might be afterwards."

Snapshots of My Father is profusely illustrated with photographs of Silber, many of them quite remarkable. There are images of him playing a trumpet, target shooting, sailing a boat, casting a bronze sculpture — striking evidence that his interests ranged far beyond philosophy and university administration, and that he refused to be handicapped by his birth defect.

During Silber's gubernatorial campaign, people who knew I had worked for him would ask what to expect if he won. "Expect a whirlwind," I always said. "Beacon Hill will be a battlefield. And state government will change, whether it wants to or not."

In the end, the voters chose not to install Silber in the Corner Office. The man who transformed Boston University never got the chance to transform Massachusetts. All the same, for anyone who knew him, Silber was a genuinely unforgettable character. And as his daughter's memoir attests, the man who was so fascinating as a public figure was no less compelling and memorable behind the scenes.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "Charitable Southerners, stingy New Englanders" Nov. 20, 1997:

The most generous state in America, according to the IRS data, is Utah, where the average taxpayer donated $4,593 to charity — almost double the national average. After Utah come Wyoming, Tennessee, Mississippi, Texas, Alabama, Arkansas, and Louisiana. With the exception of Virginia, every state of the Old South is among the top 15. None of these states is usually thought of as especially affluent. Mississippi is often regarded as the poorest state in the nation. Yet Mississippi tax filers gave an average of $3,430 to charity in 1995 — fourth-highest in the nation, hundreds of dollars more per person than New Hampshire and Rhode Island combined.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"He was soon borne away by the waves and lost in darkness and distance." — Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (1818)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.