The biggest loser

Fifty years ago today, Nov. 7, 1972, President Richard Nixon was reelected to the White House in a massive landslide. Together with his running mate, Vice President Spiro Agnew, he carried every state but Massachusetts (and the District of Columbia) and garnered 520 votes in the Electoral College. Nationwide, Nixon attracted nearly 18 million more votes than his Democratic opponent — the widest popular vote margin in American history.

Within two years, both Nixon and Agnew would be out of office. Watergate would metastasize into a "long, national nightmare." One of the biggest winners in US politics would end his career in disgrace.

Nixon remains one of the most paradoxical of presidents: Though painfully introverted and socially maladroit, his political rise was meteoric: from freshman congressman to a winning national ticket in just six years. He craved a life of transcendent influence and purpose, yet wound up a reviled figure, fuming over his list of enemies. He ran for president on a pledge to "Bring Us Together," but left a more deeply divided people in his wake. To liberals he was anathema, but his policy legacy was far from conservative. Nixon oversaw a vast expansion of the federal government, signed the Voting Rights Act of 1970 and Title IX legislation in 1972, launched the Environmental Protection Agency, withdrew all US troops from Vietnam, and set in motion the normalization of US relations with Communist China.

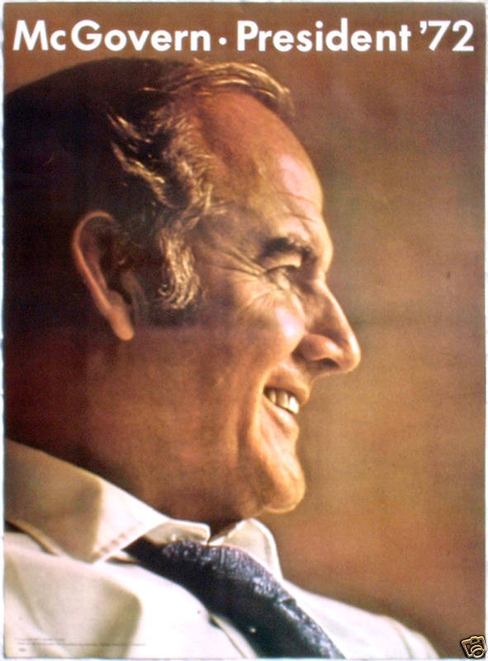

Set all that aside. On this 50th anniversary of Nixon's electoral triumph, I want to praise George McGovern, the man he defeated.

Had I been old enough to vote in 1972, I'm sure that, like most Americans, I would have voted for Nixon. McGovern was widely seen as the candidate of "acid, amnesty, and abortion." The label wasn't accurate — McGovern wanted to decriminalize only marijuana and he believed abortion should be regulated by the states — but it reflected the radical turn that the Democratic Party had taken, alienating millions of its followers in the process. "McGovernism" became a synonym for the far-left edge of the Democratic Party. Most Americans in 1972 didn't want to buy what the Democrats were selling.

Yet while McGovern's politics were certainly left-of-center, he was no wild-eyed radical. His personal values reflected classic heartland conservatism. He was a World War II bomber pilot who flew 35 combat missions and was decorated for valor, but refused to boast of his bravery on the campaign trail. He was a devoted St. Louis Cardinals fan. He loved singing hymns in the Mitchell, S.D., church he belonged to all his life.

McGovern's politics were certainly left-of-center, but his personal values reflected classic heartland conservatism. |

"I always thought of myself as a good old South Dakota boy who grew up here on the prairie," McGovern told The New York Times in 2005. "My dad was a Methodist minister. I went off to war. I have been married to the same woman forever. I'm what a normal, healthy, ideal American should be like."

Politically correct liberals and Democrats stopped talking that way long ago. Then again, over time McGovern had less and less patience for PC orthodoxy. After leaving Congress, he bought a small Connecticut hotel, the Stratford Inn, which eventually failed. That experience in the private sector proved a rude awakening, and helped him understand the misery that government often inflicts on small businesses.

"I'm for a clean environment and economic justice," McGovern said in 1993, but those worthy goals do not justify "the incredible paperwork, the complicated tax forms, the number of minute regulations, and the seemingly endless reporting requirements that afflict American business." Many small enterprises "simply can't pass such costs on to their customers and remain competitive or profitable."

He regretted not having learned that earlier. "In retrospect," he wrote in a letter to The Wall Street Journal, "I wish I had known more about . . . the difficulties business people face every day. That knowledge would have made me a better US senator and a more understanding presidential contender."

Yet even in 1972, McGovern sensed that the federal behemoth was out of control.

"Government has become so vast and impersonal that its interests diverge more and more from the interests of ordinary citizens," he told an audience just days before the election. "Washington has taken too much in taxes from Main Street, and Main Street has received too little in return. It is not necessary to centralize power in order to solve our problems."

Would that Democratic presidential hopefuls still spoke that way.

Fifty years ago today, George McGovern went down to epic defeat. I don't know that the country would have been better off had he won. But I'm quite sure that American politics would be better off if it attracted more people like McGovern — men and women with heartland values, an honest love of country, and the wisdom to know that the solutions to every problem are not to be found in Washington.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

My favorite Caillebotte

Before he became a painter, the Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte was trained in engineering. Perhaps that explains why so much of Caillebotte's art focuses not, like that of other Impressionists, on starry nights and water lilies, but on the built environment of late-19th-century urban streets, apartment balconies, and metal girders.

In crucial ways, Caillebotte was unlike the other Impressionists. Born in 1848, he was younger than the movement's stars, including Renoir, Monet, Degas, and Cezanne. He was also a wealthy patron of the arts before he ever embarked on his own career as a painter.

I've seen two Caillebotte paintings in person. One, in the Musee d'Orsay in Paris, is The Floor Scrapers, a striking depiction of three shirtless workers, on their hands and knees, refinishing the hardwood floor of an elegant apartment. It is a work that simultaneously celebrates manual toil and sensualizes it. In its time, the painting, perhaps because of its half-nude urban workers, was deemed vulgar and unseemly; when Caillebotte first tried to exhibit it at the prestigious Salon in 1875, it was rejected. Today, The Floor Scrapers is considered a masterpiece.

At the Art Institute of Chicago I've viewed another famous Caillebotte work: Paris Street, Rainy Day, which shows a street scene of people walking in the rain beneath umbrellas. If you've watched "Ferris Bueller's Day Off," you've seen this painting — in one scene, a long line of handholding students walks past it in the art museum.

But the Caillebotte I like best is far less animated than either of those. It is On the Europe Bridge (Sur le Pont de l'Europe) and it shows nothing more dramatic than two men standing on an iron bridge as a third hurries past. Both men are seen from behind. One, elegant and top-hatted, is looking through the girders at the busy Saint-Lazare train station in the distance; the other, wearing a workingman's coat but a fashionable bowler hat, seems to be gazing at the train tracks. Caillebotte lived near the bridge and painted it on at least one other occasion as part of a cityscape with buildings, people strolling, even a dog. But in this later work, the bridge itself is the main feature. Caillebotte zooms in on a single section of the bridge's massive iron trellis, its rivets and beams rendered in a chilly blue-gray.

That bluish cold pervades virtually everything in the painting: the struts of the bridge, the coat and top hat of the central figure, the train station. Even the hands of the gentleman in the top hat are tinged in blue, as is the puff of smoke indicating a steam engine getting underway. The weather is frigid, but not too cold to keep passersby from pausing to admire what were then technological marvels: a great railway station and the intricate metal engineering of the latest bridgework. (A few years later, with the opening of the Eiffel Tower, an even more intricate example of 19th-century metalwork would take pride of place in Paris.)

A short children's video produced by the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, which owns On the Europe Bridge, calls attention to an intriguing detail about the three men in the painting: The only part of the face that can be seen in all three is an ear. Perhaps Caillebotte was hinting that, to anyone in the vicinity of Saint-Lazare and its rail yards, no sensation would have been more dominant than the wails, whistles, clacks, and squeals of approaching and departing trains.

Above all, what comes across is the contrast between the severe geometry of the bridge section and the unpredictable asymmetry of the human figures who happen to be standing on it at a given instant. It's like a snapshot — an unposed "photo" of people who don't know their image is being captured and are making no effort to arrange themselves for the artist. Unlike the mass-produced components of the bridge and the train station in the distance, so rigidly engineered and unvarying, the people seen here are free to come and go, to stand where they like, to ignore the artist's gaze altogether — and, for that matter, to ignore each other.

Photography, still in its early decades when Caillebotte took up painting, changed the way artists perceived their surroundings. This work in particular reflects a photographer's sensibility. Everything is tightly cropped. No one and nothing is rendered complete. There is no beginning or end; nothing is shown from top to bottom. It's as though Caillebotte, viewing the bridge from a distance, had suddenly zoomed in with a telephoto lens, narrowing the angle of view — capturing less of the scene but more of the detail.

"What a baffling conception this is," wrote the late art historian Kirk Varnedoe, "so devoid of information and yet so evocative." That is how it strikes me, too, and why I like it so much.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"Every government is a parliament of whores. The trouble is, in a democracy the whores are us." P. J. O'Rourke, Parliament of Whores (1991)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.