Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, begins this Tuesday just before sundown and will last until nightfall on Wednesday. It is the holiest day of the Jewish year — 25 hours without food or drink, extended services in the synagogue, and a liturgy heavily focused on introspection, confession of sins, pleas for forgiveness, and undertaking to mend our ways going forward.

But this is not an essay about observing Yom Kippur. I want to write instead about two American presidents who to my mind epitomize the spirit of Yom Kippur — men who behaved badly, came to regret their misdeeds, and then demonstrated the sincerity of their repentance by permanently changing for the better.

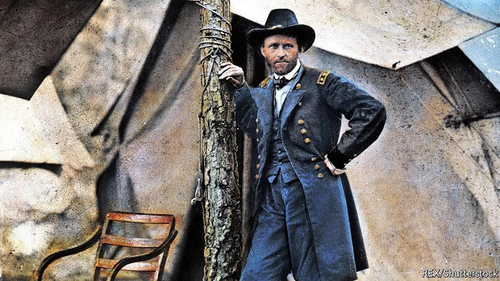

The first is Ulysses S. Grant. In December 1862, as a major general in the Union Army, he issued a directive banishing all Jews "as a class" from the vast war zone known as the Department of the Tennessee. General Orders No. 11 was the most notorious antisemitic edict ever issued by an official of the US government.

Grant's directive was triggered by his frustration with the smugglers and profiteers who were undercutting Union efforts to suppress the black market in Southern cotton. Some of those speculators were Jewish, which was enough to fuel a popular stereotype that Jews were the worst offenders. When he learned that his own father had teamed up with three Jewish traders from Cincinnati in a scheme to procure cotton at a discount, Grant lashed out in anger, and issued the order expelling all Jews from the territory he commanded "within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order."

The region commanded by Grant was home to several thousand Jews, including men in uniform serving under him. Fortunately, his order had little direct impact on most of them. Jews were forced out of Paducah, Ky., and some towns in Mississippi and Tennessee, and there were reports of Jewish travelers who were imprisoned and roughed up. But a breakdown in military communications slowed the spread of Grant's directive, and at least some officers had qualms about enforcing it. One Union commander, Brigadier General Jeremiah C. Sullivan, commented acidly that "he thought he was an officer of the Army and not of a church."

Grant's order expelling the Jews was the most antisemitic edict ever issued by a US government official. He was ashamed of it for the rest of his life — and strove to make amends. |

Needless to say, the American Jewish community was horrified by Grant's decree and petitioned President Abraham Lincoln to countermand it. The Missouri lodges of B'nai B'rith, a Jewish fraternal society, publicly beseeched Lincoln "to protect the liberties even of your humblest constituents," who had been "driven from their homes, deprived of their liberty, and injured in their property without having violated any law or regulation."

Lincoln acted with gratifying speed. Learning of Grant's order on Jan. 3 — two days after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect — he immediately revoked it. Grant accepted the revocation without protest, and offered no defense of his actions when Congress debated the incident. He didn't need to. Within two years, Lincoln would promote him to the lofty rank of lieutenant general and give him command of all Union armies. When Grant accepted the Confederate surrender at Appomattox he became a national hero. He was elected the nation's 18th president in 1868 and was reelected four years later.

Yet for all his success, Grant was ashamed of what he had done in Tennessee. "What his wife, Julia, called 'that obnoxious order' continued to haunt Grant up to his death," historian Jonathan Sarna wrote in a fine book recounting the episode, When General Grant Expelled the Jews. "The sense that in expelling them he had failed to live up to his own high standards of behavior, and to the Constitution that he had sworn to uphold, gnawed at him."

Not surprisingly, Grant's order was resurrected by his opponents in the 1868 campaign. He acknowledged that General Orders No. 11 had egregiously violated basic American values. "I do not pretend to sustain that order," he wrote humbly. "It would never have been issued if it had not been telegraphed the moment it was penned, and without reflection."

That may sound like a candidate's boilerplate. But Grant meant it. He had come to regard his order as a blot on his reputation and was determined to make amends. As a result, the eight years of the Grant administration proved a golden age for American Jewry.

During his time in the White House, Grant appointed more Jews to federal office than any of his predecessors — including to positions, such as governor of the Washington Territory, previously considered too lofty to be offered to a Jew. He opposed efforts to add an amendment to the Constitution designating Jesus as "the Ruler among the nations." He became the first president to publicly condemn the mistreatment of Jews abroad. "The sufferings of the Hebrews of Rumania profoundly touches every sensibility of our nature," Grant said in 1870 — a sensibility he underscored by the unprecedented selection of a Jewish consul general to Bucharest.

Late in his second term, Grant became the first American president to attend the dedication of a new synagogue, Washington's Adas Israel. His appearance was a powerful symbol of Judaism's acceptance in American life. "The man who had once expelled 'Jews as a class' from his war zone personally came to honor Jews for upholding and renewing their faith," wrote Sarna. For good measure, he made a substantial personal donation to the new congregation's coffers. Even more impressive: He remained through the entire three-hour ceremony.

This was repentance of the highest order — not merely a pro forma apology, but a heartfelt change of attitude and behavior that lasted a lifetime. When he died in 1885, Grant was fervently mourned in the nation's synagogues. "Seldom before," one Jewish newspaper observed at the time, "has the Kaddish [the prayer recited by Jewish mourners] been repeated so universally for a non-Jew as in this case."

Yet if the atonement of the 18th president was remarkable, that of the 21st was perhaps even more so. Grant's remorse was for a specific odious deed he had committed once. But Chester Alan Arthur turned his back on a lifetime of corruption, renouncing the very system that had brought him to the heights of influence.

When Arthur became president of the United States, he was widely viewed as a political hack — an unscrupulous partisan crony who had risen to power as a lackey of Senator Roscoe Conkling, the sleazy boss of the New York Republican machine.

The prospect of Arthur in the White House, lamented the Chicago Tribune, was "a pending calamity of the utmost magnitude." The eminent diplomat and historian Andrew Dickson White recalled that the most common reaction to the news in political circles was: "Chet Arthur, president of the United States?! Good God!"

When Arthur entered political life, the so-called "spoils system," under which most federal jobs were handed out as rewards to loyalists and flunkies of the party controlling the White House, was at its peak. It was a thoroughly corrupt system, fiercely defended by a Republican faction called the Stalwarts. The most powerful Stalwart of them all was Conkling, and Arthur was Conkling's protégé. In 1871, Conkling saw to it that Arthur was appointed collector of the Port of New York, one of the most lucrative positions in the entire government — a post all but designed for the enrichment of crooked pols.

After a lifetime of corrupt hackery, Chester Arthur became a champion of reform as president. |

Arthur exploited his post for the benefit of Conkling's network. "The nation's largest custom house became a hive of rigged hiring, illegal kickbacks, and political patronage: the spoils system at its most brazen," I wrote in a 2018 Globe column.

During political campaigns, every employee was required to pay an "assessment" — a cash contribution to the Republican Party. Jobs went to party loyalists, who routinely passed the application exam with flying colors — even when they didn't know any of the answers.

By the 1870s, disgust with the spoils system was rising in both parties. [Rutherford B.] Hayes, a leader of the GOP's reform wing, had run for president on a platform of dismantling the sleazy arrangements perfected by Conkling's machine. On his first day in office, he had called for "thorough, radical, and complete" reform of federal hiring. He instructed the Treasury Department to investigate political manipulation and fraud at the nation's custom houses, and when it produced a scathing report on the unscrupulous practices in the New York Custom House, Hayes sacked the man who ran it.

But far from wrecking Arthur's career, losing his job made him a hero to the Stalwarts. At the 1880 Republican national convention, Arthur was named to head the New York delegation. He and the other Stalwarts couldn't prevent their party from nominating another reformer to succeed Hayes — the widely-admired James A. Garfield. But Republicans knew they couldn't win the November election if Garfield didn't carry New York, and New York — Conkling's empire — was Stalwart territory. So to "balance" the ticket, Garfield's campaign offered the vice-presidency to Arthur.

Sure enough, the GOP won the general election. Arthur became vice president. But he remained every bit the partisan hack he had always been. He used the vice presidency to advance Conkling's interests, not even pretending to back the new president's reform agenda.

Then Garfield was murdered.

On July 2, 1881, Charles Guiteau, a madman who wanted to be an ambassador, shot Garfield for refusing to take his request seriously. "I am a Stalwart, and Arthur is president now!" Guiteau shouted as he was arrested, in the apparent belief that the elevation of a spoils system diehard to the White House would be his own ticket to diplomatic glory.

For two months, Garfield clung to life. His death was a terrible one, slow and painful. And all the while, Arthur was wracked with grief and fear. "I pray to God that the president will recover," he said. "God knows I do not want the place I was never elected to." When Garfield finally succumbed to his wounds, reporters came to get the new president's reaction. Arthur's valet told them he couldn't disturb Arthur, for he was "sitting alone in his room sobbing like a child, with his head on his desk and his face buried in his hands."

Garfield's death made Arthur president, but he took no joy in his accession to the highest office in the land. The knowledge that a good man had been murdered so that he could take his place and preserve the corrupt patronage system haunted him — and changed him.

To the fury and disgust of Conkling and the Stalwarts, Arthur turned firmly against the spoils system he had always championed. When Garfield's inner circle resigned, Conkling expected to be offered a top cabinet position. He also assumed Arthur would name a reliable Stalwart to take over the lucrative New York Custom House. But Arthur was no longer taking orders from Conkling. After years of doing everything he could to block civil service reform, Arthur was now a leading proponent. Having acceded to the presidency as a result of Garfield's death, Arthur said, he considered himself "morally bound to continue the policy of the former president." Outraged, Conkling returned to New York and denounced Arthur as a traitor.

As I noted in the column, however, Arthur was only getting started.

In a formal message to Congress, he explicitly recommended an overhaul of federal hiring practices. Those who had assumed he would blithely endorse corruption as usual were astonished by the president's good-government agenda. Civil service reform groups sprang into action around the country. Senator George Pendleton of Ohio, a Democrat, introduced a bill to mandate merit-based hiring in many federal agencies. Arthur endorsed it.

"Thus did a champion of the Stalwarts drive the first nails into the coffin of political patronage," I wrote. With Arthur's support, the Pendleton bill sailed through both houses of Congress. On January 16, 1883, Arthur — the former Conkling lackey, the ultimate creature of unscrupulous Republican bossism — signed it into law. He appointed qualified members to the new Civil Service Commission, and firmly enforced the commission's new rules.

This was atonement of extraordinary purity. History offers few examples of powerful men or women who are moved from within to mend their sordid practices at just the moment when those practices have rewarded them with unparalleled success. Today Arthur is commonly regarded as one of the nation's least impressive presidents. But when his term in the White House was over, he was widely praised. The Nation — a publication long associated with the cause of patronage reform — described Arthur as the best president since Lincoln. Even the cynical Mark Twain agreed. "It would be hard indeed to better President Arthur's administration," he wrote.

Most of us, I imagine, have had twinges of regret for our behavior. Many people have felt the pain of remorse and resolved to improve, only to fall short when temptation reappears. At the center of the Yom Kippur liturgy is a lengthy formal confession of sins of all kinds, repeated numerous times over the course of the day. From year to year, the list of offenses never alters — a realistic reflection of the fact that, from year to year, most of us never truly alter either. Genuine penitence is hard. It isn't being sorry for what we have done. It isn't determining earnestly not to do it again. It is following through on that determination, remaking ourselves into the kind of person who wouldn't do it again, even when doing so would be easy.

In the annals of American politics, repentance and atonement play very minor roles. Grant and Arthur are towering exceptions. Their stories are inspiring reminders that within each of us is the power of self-transformation — that people of any faith, or of no faith, can create a new and improved version of themselves. It isn't easy. It isn't common. But it isn't impossible. If Ulysses Grant and Chester Arthur could become better, any of us can.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.