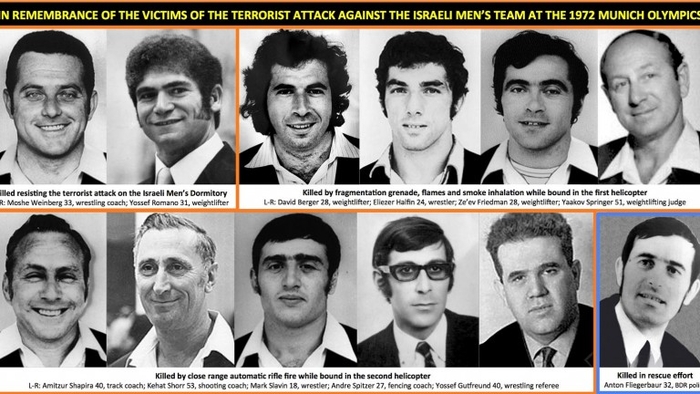

The victims of the terrorist massacre in Munich |

FIFTY YEARS ago next week, Palestinian terrorists invaded the Olympic Games in Munich and murdered 11 Israeli athletes. It was the worst atrocity in Olympic history. Nearly as horrifying was the reaction of the International Olympic Committee and its execrable president, Avery Brundage, who announced, almost before the bodies of the victims had grown cold: "The games must go on."

The 1972 Olympics were the first to be held in Germany since the infamous Berlin Games of 1936, which took place under Nazi supervision. The (West) German government was eager to show the world how much things had changed in 36 years — above all, that Germany was no longer to be associated with the totalitarian grimness of its past. To emphasize the ease and freedom of the new Germany, security was kept to a minimum. There was no hint of barbed wire, troops, or heavily armed police. So intent was the government on promoting the Munich Olympics as "the Carefree Games," that no one closely scrutinized identification badges. Access to the athletes' village was easily gained; anyone lacking an ID could simply climb the chain-link fence.

Which is exactly what eight Black September terrorists from the Palestine Liberation Organization's Fatah faction did early on the morning of Tuesday, Sept. 5.

Armed with Kalashnikov assault rifles, pistols, and grenades, the terrorists forced their way to the Israeli team's quarters. Two of the Israelis were shot and killed on the spot; the body of one was grotesquely mutilated. Nine other Israeli athletes were taken hostage. The terrorists demanded the release of 234 prisoners held by Israel, and insisted that Germany free the founding members of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, a far-left terror group responsible for numerous kidnappings, assassinations, and bombings.

"When the release did not materialize by the late afternoon, the terrorists demanded a plane to take them to Egypt," recounted historian Deborah Lipstadt in a 2012 essay for Tablet magazine.

German officials agreed but planned an ambush at the airport. The ambush was completely botched: A team of German police assigned to entrap the terrorists walked off the job as the terrorists were on their way to the airport. There were more terrorists than German snipers — and the snipers could not communicate with each other or with the officials in charge. Armored cars, which were ordered for backup, got caught in an hour-long traffic jam around the airport.

A gun battle erupted between the German forces and the terrorists on the tarmac, and the athletes, whom the captors had bound one to another in the helicopters that had brought them to the airport, were caught in the middle. When the terrorists realized that they could not escape, they shot the hostages and then threw a grenade into the helicopters to ensure that they were dead.

Not until 4 in the afternoon, 12 hours after the terrorist attack had begun, did Brundage finally suspend competition for the day and announce that a memorial service would be held the next morning. But at the Olympic Stadium on Wednesday, Brundage spoke only a single sentence about the Jews who had been slaughtered. "We mourn our Israeli friends, victims of this brutal assault." From that he segued into an indignant complaint about how "commercial, political, and now criminal pressure" was sullying the purity of the Olympic Games. Astonishingly, he described the murder of the 11 Israelis as the second of "two savage attacks" the Munich Games had endured. The first, in his telling, was the decision by the IOC to exclude athletes from white-ruled Rhodesia, a decision Brundage had opposed.

When Brundage declared that the Games would not be cancelled but would instead resume the next day, there was little pushback. Among the few who expressed disgust was Red Smith, the New York Times sportswriter:

"This time surely, some thought, they would cover the sandbox and put the blocks aside," Smith wrote in the column that appeared the next day.

But no. "The Games must go on," said Avery Brundage, high priest of the playground, and 80,000 listeners burst into applause. The occasion was yesterday's memorial service for 11 members of Israel's Olympic delegation murdered by Palestinian terrorists. It was more like a pep rally. . . .

Applause was loud. Obviously not everybody has been repelled by the spectacle of children returning to their play almost as soon as the killing ended. Before yesterday's gathering in the stadium, even before details of the midnight shootout were known, the Executive Committee the IOC had met and decided to resume. The meeting took 45 minutes.

"The Games should go on," said a trainer with the American team. "We shouldn't call everything off because of a political incident, and that's what this was."

In the end, nothing was called off. The surviving members of the Israeli squad returned home, accompanying the coffins of their murdered teammates. Otherwise all signs of distress were quickly obliterated. German Chancellor Willy Brandt had asked the countries participating in the Olympics to fly their flags at half-mast as a sign of sorrow and respect. But when 10 Arab nations objected, the request was rescinded.

For decades after the killings, the families of the murdered Israelis repeatedly asked that their loved ones be remembered with a moment of silence at the start of a subsequent Olympic Games. The International Olympic Committee steadfastly refused, insisting that it would be wrong to allow politics to intrude on what was meant to be an international celebration of athletic brother- and sisterhood. That was a transparently phony excuse. It was the massacre that had so brutally undermined the ideal of global solidarity the Olympics were supposed to represent. It only compounded that brutality that the families' humble request for a moment of remembrance was denied for so long.

Not until last summer, when the 2020 Olympics, delayed a year because of the Covid-19 pandemic, opened in a half-empty stadium in Tokyo, were the murdered Israeli athletes finally remembered with a moment of silence. It had been 49 years.

Meanwhile, the terrorists who carried out the horror continue to be honored and celebrated by the Palestinian Authority.

During a visit to Germany this month, Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian Authority president, was asked by a reporter if he intended to express regret for the barbaric events of 1972. Far from apologizing, Abbas, who was standing next to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, accused Israel of committing "50 Holocausts" against the Palestinians — a falsehood so ugly that Scholz said it "disgusted" him.

There is no chance that Abbas will ever repudiate the 1972 slaughter, not least because it was carried out on behalf of Fatah, the Palestinian faction that Abbas has long headed. According to Abu Daoud, the Palestinian mastermind who organized the Munich atrocity, Abbas was the senior Fatah official responsible for financing the operation. In the half-century since the terrorists invaded the Olympics, the Palestinian Authority and Fatah have consistently portrayed their actions as noble and heroic.

As recently as June, a member of the Fatah Central Committee, Tawfiq Tirawi, posted an encomium to the Black September terrorists, identifying them as the "heroes of the Munich operation." In April 2021, the Palestinian Authority's official news program aired footage of three of the killers, hailing the "pride, glory, and loyalty" they represented. In a television broadcast three years earlier, the "self-sacrificing fighters" were extolled for having "stunned the world and made it hold its breath for more than 12 hours in Munich."

These are the champions and the role models that Abbas and the Palestinian Authority teach their follwers to admire — not doctors, poets, scientists, or even athletes, but murderers. For half a century, the PA has reinforced its message of pride in the savagery of 1972. Fifty years that could have been devoted to building up the infrastructure of a Palestinian state, 50 years during which any of Israel's repeated overtures for peace could have been embraced, have been used instead to deepen and entrench the same hatred that Palestinian leaders espoused in 1972.

Because of that hatred, 11 Jewish athletes died 50 years ago next week before the eyes of a world that barely paused before returning to its games. Their names were David Berger, Ze'ev Friedman, Yosef Gutfreund, Eliezer Halfin, Yosef Romano, Amitzur Shapira, Kehat Shorr, Mark Slavin, Andre Spitzer, Yakov Springer, and Moshe Weinberg. May their memories be a blessing.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

This column is excerpted from Arguable, my free weekly newsletter. To sign up for Arguable and receive it each week by email, just click on the image below.