Abortion, opinion polls, and the Constitution

How many times in the last two weeks have you been assured that a majority of Americans want the Supreme Court to uphold Roe v. Wade? Over and over and over and over that point has been hammered home by journalists, activists, and politicians who support liberal abortion rights. Always the implication is the same: The public firmly opposes overturning the landmark 1973 ruling, so for the Supreme Court to junk Roe would amount to an autocratic and illegitimate attack on American democracy.

But that isn't what the American people think.

This much of the claim is true: When surveyed by opinion pollsters, most Americans have consistently said that Roe v. Wade should stand. For more than 30 years, Gallup has been asking respondents if they would "like to see" the Supreme Court overturn Roe, and roughly six out of 10 always say no.

Yet the evidence is strong that Americans don't actually support the permissive abortion regime that Roe and the Supreme Court's subsequent cases created.

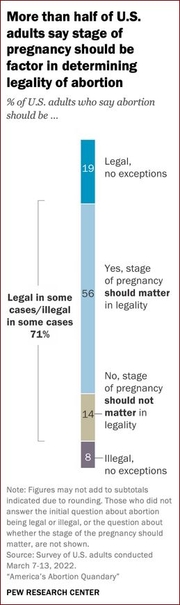

The most recent study of public opinion on abortion was published by the Pew Research Center this month. It makes clear that relatively few Americans are abortion-rights absolutists. Asked whether abortion should be legal in all cases, only 19 percent of respondents agree. That is another way of saying that four-fifths of American adults believe that there should be at least some restrictions on when a pregnancy can be aborted.

"The survey data show that as pregnancy progresses, opposition to legal abortion grows and support for legal abortion declines," Pew reported. At six weeks of gestation, for example, only 21 percent of the public would ban abortion outright, while 44 percent would permit it. But "at 14 weeks, the share saying abortion should be legal declines to 34 percent, while 27 percent say illegal and 22 percent say 'it depends.'"

And at 24 weeks? Under Roe (as modified by Planned Parenthood v. Casey), abortion for any reason is permitted until that point, which is roughly when the fetus reaches viability. But Pew's survey found that a plurality of Americans (43 percent) believe that abortions should be illegal by that point. Only 22 percent say that abortions at 24 weeks should be lawful.

Even among abortion supporters there is agreement that "how long a woman has been pregnant should matter in determining legality of abortion." Of the 61 percent of US adults who told Pew that abortion should generally be legal, more than half nonetheless agree that after a certain point in gestation, it should be illegal to abort a healthy pregnancy.

There are other limitations on abortion, currently barred under Roe and Casey, which most Americans support. According to Pew, "large numbers of Americans favor certain restrictions on access to abortions. For instance, seven-in-ten say doctors should be required to notify a parent or legal guardian of minors seeking abortions." No such notification is required by Roe. In 2020, Massachusetts lawmakers, overriding Governor Charlie Baker's veto, enacted a law guaranteeing girls as young as 16 an unfettered right to abortion without the approval of a parent or even a judge.

"Combined with the 8 percent of US adults who say abortion should be against the law in all cases with no exceptions," summarizes Pew, "this means that nearly two-thirds of the public thinks abortion either should be entirely illegal at every stage of a pregnancy or should become illegal, at least in some cases, at some point during the course of a pregnancy." Clearly this undercuts the narrative that most Americans do not want Roe overturned. And Pew is far from alone in saying so.

According to The New York Times, a bastion of support for abortion rights, two-thirds of Americans support banning abortion after the first trimester. The first trimester ends at 12 weeks; the Mississippi abortion law currently before the Supreme Court doesn't ban abortion on demand until after 15 weeks.

When the Associated Press and the National Opinion Research Center released a survey on abortion policy last summer, here is how the AP story began:

A solid majority of Americans believe most abortions should be legal in the first three months of a woman's pregnancy, but most say the procedure should usually be illegal in the second and third trimesters, according to a new poll. . . .

The new poll . . . finds 61 percent of Americans say abortion should be legal in most or all circumstances in the first trimester of a pregnancy. However, 65 percent said abortion should usually be illegal in the second trimester, and 80 percent said that about the third trimester."

None of this should come as a surprise. Numerous opinion surveys over the years have documented public support for limiting abortion, even among voters who say they oppose reversing Roe. Majorities of Democrats, reported Gallup in 2011, favored laws requiring women to be notified in advance of the risks associated with abortion. Most Democrats also backed a 24-hour waiting period for abortions, parental consent for minors, and a ban on "partial-birth abortion."

In the abstract, then, most voters say that Roe should not be overturned. But when they are asked about specifics, they have long made it clear that abortion for any reason at any time is not an arrangement they support. For all its iconic status, Roe's legal details are not something people know that much about. The rage inspired by Justice Samuel Alito's draft opinion overturning Roe likely reflects the belief that overturning the 1973 landmark would make all abortions illegal. That simply isn't true. Without Roe, abortion policy would revert to the states, many of which — including California, New York, Illinois, and Massachusetts — have already codified a right to abortion.

In any case, what legitimate purpose is served by asking whether Roe should be overturned? Would any serious person argue that Supreme Court cases should be decided on the basis of public opinion? When Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered Japanese Americans to be forcibly incarcerated in internment camps, he did so with massive public support. Does that mean that the high court was right to uphold the legality of those internment camps in the 1944 case of Korematsu v. United States? During the decades when Jim Crow segregation was pervasive and popular, public opinion would have opposed toppling Plessy v. Ferguson, the shameful Supreme Court decision that legalized "separate but equal" public accommodations for Americans of different races. Did that mean it was right for Plessy to remain in force for as long as it did?

The Constitution grants life tenure to federal judges precisely so they should not be swayed by mass sentiment and the passions of activists, politicians, and the press. Sometimes the Supreme Court rules wisely, sometimes it blunders, but the last thing we should want is for its analysis of constitutional controversies to be influenced by public emotionalism and politicians playing to the mob.

Should Gallup, Pew, and other polling companies test public opinion on whether the Federal Reserve ought to raise its basic interest rate by 25 basis points or 50 basis points? Should they have conducted surveys before the Food and Drug Administration approved the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine? Would former Vice President Mike Pence have been well-advised to check with a pollster about whether to certify, on Jan. 6, 2021, that Joe Biden had been duly elected president of the United States?

We may live in a democratic republic, but not every question of public policy and governmental administration is supposed to be determined on the basis of popular will. Poll numbers are irrelevant to the pharmaceutical approval process. They should be just as irrelevant to constitutional jurisprudence.

Not one American in a thousand can analyze the legal reasoning in Roe and Casey — or in the draft Alito opinion overruling them. Whether and to what extent abortion should be legal is very much a political question, well suited to the democratic process. Whether and to what extent Roe and Casey correctly analyzed what the constitution mandates about abortion is a judicial question. The difference between the two goes to the heart of America's tripartite system of government.

Under liberal Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s "overruled a staggering number of precedents." |

The fulmination of politicians and the hyperventilation of the media notwithstanding, overturning a Supreme Court precedent, even one half a century old, is not a shocking violation of judicial ethics or integrity. It is part of the court's job.

Akhil Reed Amar, a professor of constitutional law at Yale (and a self-described "Democrat who supports abortion rights but opposes Roe"), pointed out in a weekend essay that "an essential function of the Court is to revise incorrect or outdated prior rulings" and that over the last century, "the court has overruled itself about twice a year — roughly the same rate at which the court has overturned acts of Congress." Amar continued:

Precedents fall for many reasons. Sometimes the world changes in ways that mock the logic and expectations of the old ruling. Sometimes opposing lines of cases evolve and clash, and something must give. Most fundamentally, sometimes the court comes to believe that an old case egregiously misinterpreted the Constitution, so the old case must go. . . .

[T]he New Deal Court properly repudiated dozens of earlier Gilded Age cases that read property and contract rights far too broadly and in the process invalidated minimum-wage, maximum-hour, worker-safety and consumer-protection laws of various sorts—laws that are now seen, quite rightly, as perfectly proper.

The liberal Warren Court also overruled a staggering number of precedents, introducing now familiar terms to our constitutional lexicon. Mapp v. Ohio (1961) dramatically expanded the "exclusionary rule," Reynolds v. Sims (1964) sweepingly mandated "one person, one vote," and Miranda v. Arizona (1966) required the now iconic "Miranda warning." These cases and dozens like them jettisoned earlier settled precedents that, in the minds of the justices, mangled the Constitution. As law professor Philip Kurland once wryly observed, "The list of opinions destroyed by the Warren Court reads like a table of contents from an old constitutional casebook."

Today, the Supreme Court's 1973 opinion in Roe v. Wade, written by Justice Harry Blackmun, is similarly ripe for reversal. In the eyes of many constitutional experts across the ideological spectrum, it too lacks solid grounding in the Constitution itself.

Reasonable scholars, judges, and students of the law can disagree about that, of course. It seems quite likely that at least three sitting justices will do so in vigorous dissents. Whether the court got Roe right or wrong in 1973, however, cannot be calculated by looking at polls. The histrionics of the last few weeks have been, like so much else in these polarized times, an embarrassment. Let's hope the court can tune out the frenzy and focus on doing its job.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What Would Jesus Say (on economics)?

I don't suppose that business schools commonly assign religious texts to their students or that instructors of theology are in the habit of putting business writings on the syllabus, but the Reverend Robert Sirico has just published a volume that could fit both bills. The Economics of the Parables, a strikingly original, thoughtful, and absorbing book, focuses on the some of the most famous stories of all time — the parables attributed to Jesus in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew.

A new book fuses the teachings of Jesus through his parables with an appreciation for liberty and market economics. |

Sirico is a Catholic priest, the pastor emeritus of Sacred Heart of Jesus Parish in Grand Rapids, Mich., and the co-founder of the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty. In the 1970s he was a radical activist, an associate of Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda and an early crusader for same-sex marriage. He believed, as he once put it, that "a baptized form of Marxism was next to godliness." Over time, he moved rightward, becoming an eloquent defender of limited government, economic freedom, and the virtues of capitalism — as well as a devout exponent of traditional Christian teachings about justice and charity. Sirico argues that there is no contradiction between those teachings and the rigors of the marketplace — and Jesus, he says, was of the same view.

To prove the point, he analyzes 13 of Jesus's parables. Like any good preacher, Jesus frequently drew on "real life" to make his points. It is no coincidence that so many of his parables deal with money, business, and the workplace, and you don't have to be a Christian to appreciate the economic lessons that Sirico draws from them.

I am an observant Jew, and my religious tradition does not regard Jesus as a prophet or a messiah, let alone as the son of God. To Jews, the New Testament is not a divine revelation. Nevertheless, I appreciate that billions of Christians over the past 20 centuries have regarded Jesus as divine, and no one can deny the Gospels' profound influence on human history, morality, and idealism. Even apart from religion, the parables of Jesus endure for their literary and psychological power. As with all great stories, they remain timeless and relevant, notwithstanding the nearly unimaginable changes that have taken place since the era in which they first appeared.

Some of the parables are no more than a sentence or two in length. Here is the Parable of the Pearl in its entirety:

Again, the kingdom of heaven is like unto a merchant man, seeking goodly pearls: Who, when he had found one pearl of great price, went and sold all that he had, and bought it. (Matthew 13:45-46)

In its simplest reading, Jesus was illustrating to his followers the supreme value of gaining religious salvation. But what interests Sirico about the parable is the dignity it ascribes to the merchant and his business acumen. "He is engaging," Sirico writes,

in the kind of activity that we see taking place on the stock market every instant of every day. It is the ongoing process in every street bazaar around the world. Prices fluctuate based on human valuation, the subjective knowledge of the parties to the trade, and the availability of resources.

To many Christians (and others), businesses transactions cannot avoid being morally suspect. There is a widespread view that sincere faith is inherently antithetical to profit-seeking commerce. Many believers assume that the proper Christian attitude is to shun or downplay market activity, writes Sirico, "because somehow, rather than being based on love and the common good, business is inevitably animated by selfishness and greed." But Jesus in this parable implies nothing of the kind. He doesn't even imply that there is something frivolous or decadent about buying luxury goods like "goodly pearls". To the contrary, he depicts his fictional merchant as a man of respect, acumen, and sophistication. This merchant, Jesus pretty clearly implies, is someone who has his priorities in line.

Another of the parables analyzed in Sirico's book is that of the Laborers in the Vineyard. Briefly, it recounts how a landowner hired some hands early one morning to work in his vineyard for the day, agreeing to pay them each a denarius (an ancient Roman coin). During the course of the day, the landowner repeatedly headed back out to hire more workers, promising to pay them "whatever is right." When the day was over and the work completed, the laborers lined up to be paid. To the dismay of the men who had been working since the morning, the owner decided to pay everyone a denarius — even those who were hired when the workday was almost over. The owner dismisses their complaints of unfair treatment, pointing out that he paid them exactly what they agreed on. If he wants to pay those hired later the same amount, he asks, doesn't he have a right to do so?

The theological meaning of the parable is presumably that those who come to Jesus late in life are rewarded as abundantly as those who did so in their youth. But this is a book about economics.

Sirico sees in Jesus's landowner an entrepreneur who realized that he was facing "the potential catastrophe of a substantial part of the harvest's being lost because of a shortage of workers." Eventually he had enough men to get the job done and — perhaps feeling jubilant that everything worked out well — he generously paid all the men a full day's wage. When those who had worked all day griped at the handsome sum paid to those who joined the work crew late in the day, the employer referred to the terms the workers themselves had accepted that morning. "Thus, as the landowner rightly pointed out," Sirico comments, "their complaint was not about their own paycheck but the paychecks of others. . . . [E]ven if we are unwilling to celebrate the good fortune of others, we surely have no right to condemn it and begrudge them."

This parable raises interesting questions about the tension between "equal pay for equal work" vs. the right of workers and employers to negotiate mutually acceptable terms of employment. It underscores the importance of adhering faithfully to contractual terms. It speaks to the phenomenon of rapidly rising prices in a tight market. Most significantly, perhaps, it makes a key point about how values are calculated:

Rewards in a market economy are not distributed as Karl Marx imagined them to be. Prices and wages are not determined by the amount of sweat and muscle expended; they are determined by the subjective value of the final product. . . . Economists would say that this value is "imputed back" to all of the factors of production.

To the landowner in the parable, the price of the labor required to get his crops in by the deadline rose steadily during the day, so he made the necessary adjustments. In much the same way, vendors confronted with a sudden scarcity of merchandise sometimes sharply raise prices to keep their shelves from rapidly emptying out. We are accustomed to politicians howling in such cases about the sinfulness of price "gouging." His parable about Laborers in the Vineyard suggests that Jesus would take a different view.

The Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard, by Jacob Willemsz de Wet (17th century) |

Equally shrewd are Sirico's insights into the other parables, including the ones about the Talents, the Sower, the Good Samaritan, and the Two Debtors. Time and again, he shows that Jesus honored those who engage in business, who use private property wisely, who spot opportunities to make money that others overlook, and who channel their assets into good works. Jesus seems to have taken it for granted that voluntary economic activity helps maintain social order and increase human happiness. He seems to have looked upon entrepreneurs not as greedy exploiters but as individuals driven by hope, faith, and confidence to achieve a meaningful reward.

To be sure, there are passages in the New Testament that appear to cut the other way — the one about how difficult it is for a rich man to enter Heaven, for example, or "blessed are the poor" in the Beatitudes, or the story of Jesus throwing the money changers from the Temple. Far from avoiding them, Sirico devotes an entire fascinating chapter to analyzing them closely. They too, he argues, uphold a Christian approach to economic liberty and robust markets that works to advance the common good.

The Economics of the Parables is a slim but brilliant volume, fresh and eye-opening. I thought I was familiar with the parables of the New Testament. I am grateful to Father Sirico for illuminating for me just how much was in them that I never noticed.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "Clinton's own deeds merit an apology," May 22, 1997:

It's nice that Bill Clinton feels remorse for the malfeasance of his predecessors. It would be better if he felt remorse for the malfeasance of Bill Clinton.

From a president whose own administration is under investigation by a quartet of special prosecutors, whose aides keep resigning in disgrace, whose longtime confidants get indicted and convicted, whose political goons rifle hundreds of confidential FBI files, who is described by more than half the electorate as not honest or trustworthy, whose personal behavior is malodorous with scandal, whose response when caught red-handed is to shrug, "Mistakes were made" — from such a president, homilies on the immoral acts of administrations past are just a little hard to take.

There are blots on the legacies of Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower. But if Clinton wants to atone for presidential sins, he needn't go back 60 years to find them. He can start by apologizing for his own.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"And now go, and make interesting mistakes, make amazing mistakes, make glorious and fantastic mistakes. Break rules. Leave the world more interesting for your being here. Make good art." — Neil Gaiman, University of the Arts commencement address (May 17, 2012)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.