RARELY DO The Washington Post and the New York Post report the same story in the same way. The two legendary dailies embrace wholly dissimilar styles of news coverage. One is solid, steady, authoritative; the other is feisty, fearless, quick. One is a mainstay of the establishment media; the other is Rupert Murdoch's US flagship. Offhand, it would be hard to think of two papers with less in common.

Yet last Friday, from both their front pages, leaped the identical headline:

Yet last Friday, from both their front pages, leaped the identical headline:

"Snuffed Out."

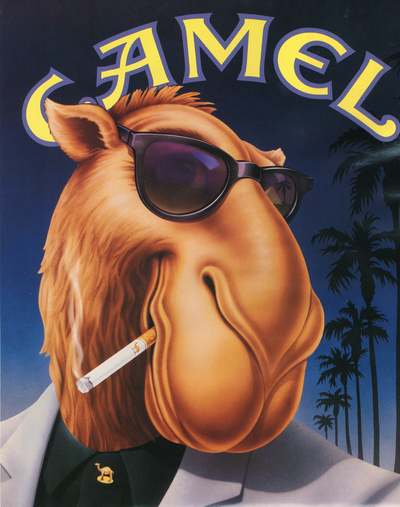

They were reporting, of course, the dropping of "Joe Camel," that sly, smooth smoker of a thousand R.J. Reynolds ads. It is revealing that two newspapers so completely unalike would reach for the same violent idiom to describe, of all things, an advertising decision. "Snuffed out." Is this just about cigarettes?

Certainly it was no ordinary business decision. Joe Camel isn't being dropped because of normal market considerations. He isn't being dropped because his market share fell off, or because the antismoking lobby turned public opinion against him. On the contrary. Nine years after Joe was introduced, his commercial and popular appeal are as potent as ever. He has been under attack almost from the hour he appeared, but the hysteria of the tobacco foes has never made a dent: Joe just has a way with smokers.

(Though not with nonsmokers, especially young ones. For all his supposed appeal to children, Joe has never had much luck in persuading them to smoke. In 1985, two years before Joe's arrival, 29.4 percent of kids 17 and under smoked. By 1990, that percentage had declined to 22.4. In 1995, it was down to 20.2.)

All advertising icons are eventually laid to rest, but not when their power is at its peak. It is no more in R.J. Reynolds' interest to inter Joe Camel than it would be in Energizer's interest to pull the plug on its bunny. But Joe isn't dying of natural causes. He is being assassinated. He is being, as the Washington and New York Posts bluntly put it, "snuffed out."

And his assassin? The government of the United States.

Oh, pish, you say. The government assassinating a cartoon character? What overwrought tripe.

But maybe it would sound less overwrought if we started referring to Joe Camel by his proper title:

He was a message.

Whatever you think of the product he was created to sell, Joe Camel - like all advertisements and commercial symbols — was a message. He was an exercise of free speech. He was the expression of an opinion — an opinion agreeable to some, disagreeable to others, but widely held and unmistakably real. "Joe Camel" is no less filled with meaning — and no less entitled to a stall in the marketplace of ideas — than "Look for the union label" or "Heather has Two Mommies" or "I want to build a bridge to the 21st century." The fact that it is not in people's best interest to smoke is irrelevant to the question of free speech. It is not in people's best interest — many would argue — to join labor unions, live as lesbians, or vote for Bill Clinton. Should messages promoting those choices be silenced by the government, too?

It is anchored in the bedrock of American freedom that the state does not decide which views may be heard. The Bill of Rights does not command the government to stifle erroneous messages. It commands the government to "make no law . . . abridging freedom of speech."

Some ad executives wanly suggest that there was nothing uncommon about R.J. Reynolds's decision to retire Joe Camel. "It's not unusual in the advertising world," maintained Daniel Jaffe of the Association of National Advertisers, "for even wildly successful and popular campaigns to change." Reynolds itself said it was voluntarily shelving Joe to make way for a new series of ads.

It would be nice to think so. But the truth, not nice at all, is that Reynolds was censored. From the president down, the federal government waged a naked campaign of intimidation. Reynolds — not smoking, Reynolds — was savaged by the Food and Drug Administration, by the Federal Trade Commission, by the surgeon general, by the attorney general, by scores of members of Congress. And when the company's message was strangled at last, the government reveled in its kill.

"I'm very happy to say goodbye to Joe Camel," chortled Health and Human Services Secretary Donna Shalala.

"Joe Camel is dead — he had it coming," gloated Bruce Reed, Clinton's domestic policy adviser.

"This is a step in the right direction," Al Gore said, "but there's still more to do."

There is always more to do. There is always some other message, somebody else's speech, that needs to be turned off. There are movies and TV shows that the government might have to quash. There are wine and liquor ads the feds may decide to target. There are cosmetics companies whose views ought to be censored. There are automobile commercials that could mislead young people. There are hazardous Web sites to be restricted, intolerable magazines to be controlled, talk-show hosts to be put in their place.

"There's still more to do," says Al Gore. The government won't stop with Joe Camel's scalp. He is only the latest message to be snuffed out — not the last.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.