My mother's son

One of my earliest political memories is of accompanying my father to the polls early on Election Day in November 1968, when I was 9 years old. That was the first time I had ever seen a voting machine, and my father let me pull the lever for Hubert Humphrey. Like more than four out of five Jewish voters that year, my father supported the Democratic presidential nominee.

But that wasn't true of all the adults in the Jacoby household. When I got back home, I described my adventure to my mother, who cheerfully told me that she was planning to go to the polls a little later on and would be casting her vote for Richard Nixon, the Republican. There was in her tone not the slightest hint of dismay or reproach for the way my father had voted. That day, without intending to, my mother imparted a valuable political lesson, one even more relevant now than it was a half-century ago: There is no reason you can't love someone who doesn't share your politics.

In retrospect, another lesson I learned from my mother that day was that it was OK to march to the beat of a different drummer than the one favored by your community, peers, or social circle. The overwhelming majority of American Jews may have backed the candidate with the D by his name in 1968, but that didn't inhibit my mother in the least from voting for the candidate with the R. (Not that she was a party loyalist. Her favorite president, she always said, was Harry Truman, who famously described Nixon as a "bastard" who could "lie out of both sides of his mouth at the same time.")

The most distressing political shift of my lifetime has been the toxic polarization of our public discourse. Countless Americans on both the right and the left have embraced a rigid, binary approach to politics: If you don't vote as I do, you're the enemy. Thanks in part to my mother's influence, I have rarely been tempted by such thinking. Politics interested her — more, I'd say, than it interested my father — but she was neither partisan nor overly judgmental about political matters. I grew up in the Cold War and always had a visceral hostility to communism. (I still do.) Yet I can remember my mother describing to me when I was a child how appealing the message of the Communist Party had seemed to many American Jews during the dark days of the Depression. Her point wasn't that communism was good, but that otherwise good people could be attracted to it — and, by extension, to other noxious doctrines. My mother's example has made it easier for me to detest some people's political views — intolerant woke leftism, for example, or hard-right Trumpism — without automatically detesting the people who embrace them.

That is one reason — one of many reasons — I am so grateful to be Arlene Jacoby's son.

My mother on her wedding day in 1956. Her marriage to my father lasted more than 64 years. |

My mother passed away two weeks ago. She outlived my father, who died of Covid-19, by just 26 days. She had also been infected with the virus, but appeared to have beaten it, had been discharged from the hospital, and seemed to be getting stronger. That turned out to be an illusion. The damage to her lungs was too profound. On Feb. 18, struggling to breathe, she was taken back to the hospital. Four days later, she departed this life.

There was nothing shy or somber or sedate about my mother, who was born in Cleveland in 1932. She abounded with energy and humor, opinions and advice. And songs! My mother was blessed with a spectacular singing voice, and I grew up to her renditions of countless American classics. Ballads, show tunes, jazz standards, novelty songs — she sang them all. I have vivid memories of my mother singing everything from Hoagy Carmichael's "Stardust" to Frank Loesser's "A Bushel and a Peck," from Cole Porter's "Too Darn Hot" to Jimmy van Heusen's "Love and Marriage." She channeled performers as different as Johnny Ray belting out "Cry," The Mamas and the Papas' version of "Monday, Monday," and The Four Lads singing "Istanbul (Not Constantinople)."

Some of my mother's best stories were linked to specific songs. When the movie "The Jolson Story" was released, she told me, she cut class to go to the theater and sit through screening after screening, unable to get her fill of "California, Here I Come." In 1955, approaching Public Square in downtown Cleveland for the blind date she had with a man named Mark Jacoby, she instantly noticed the handsome guy whose eyes were following every passing girl — and for the rest of her life, she could never tell that story without breaking into song:

Standing on a corner, watching all the girls go by

Standing on a corner, giving all the girls the eye

Until I was 15, our family of seven lived in a small house with only one shower. For a while my mother used music to ration shower time among us five kids: You could stay under the water for as long as it took her to sing "I'm Looking Over A Four-Leaf Clover." Her rule made for some pretty speedy showers — but to this day I know all the words to that number.

And to so many others. In recent years, I would call my mother each May 1 and start singing "Mountain Greenery" when she answered the phone. (Opening lyrics: "On the first of May/ It is moving day/ Spring is here, so blow your job/ Throw your job away!") The rock-and-roll revolution left me largely untouched, but my mother bequeathed to me a lasting appreciation for the American songbook of the pre-rock era. When Dean Martin died in 1995, I wrote a column celebrating his career (really!) and wishing that I had a voice like his.

My mother overflowed with personality. She was upbeat, indomitable, and gregarious, and had a knack for winning people over. When she began dating my father, it meant interacting with his circle of Eastern European immigrants, many of them Holocaust survivors scarred by their history of loss and pain. But when my mother came on the scene, as one older relative told me last week, everything felt lighter, brighter, happier. She evoked laughter even from people who weren't used to laughing.

Yet her own early history had been anything but a barrel of laughs.

When my mother was just a toddler, her father abandoned his family. My grandmother, unable or unwilling to raise her two youngest children alone, placed little Arlene and her brother in an orphanage. She lived there until she was 11 or 12 years old, yet emerged buoyant, affectionate, and optimistic. The experience of growing up without a healthy family environment seems not to have embittered her in the least, nor stunted her ability to form long-lasting attachments. Her marriage to my father lasted more than 64 years. Some of her closest friendships were even older than that. To the last, her thoughts were of family. In the hospital, knowing that death was near, her final priority was to say goodbye to her children and grandchildren. She spoke to each one of us, telling us through her oxygen mask and gasps for breath how beloved we were. When I suggested that she was jumping the gun — that if the doctors weren't giving up on her I wasn't about to either — she gave me a flash of the we're-going-to-do-this-my-way steeliness I knew only too well: "No arguments, Jeff," she told me curtly. "No debates."

My mother was never sentimental or a pushover, least of all when it came to her kids. When I got in trouble in school, generally for mouthing off, my mother sided with the teachers. (Long-ago schoolmates still remember the day my mother showed up in our third-grade classroom to chew me out for misbehaving.) When I was in high school and expressed an interest in getting a college degree, my mother told me there was only one way to make that happen. "If you want to go to college," she said, "you'd better get a scholarship." In the years I was growing up, she was a firm disciplinarian, and when I became a parent, she succinctly summarized her philosophy on the subject of inculcating good values. "No child ever had to be taught how to hit, lie, sneak, or talk back," she said. "They have to be taught not to."

When I was little and a sometimes annoying chatterbox, my mother warned me that every person is born with a pre-ordained quota of words, and that when you've used up your allotment, you stop speaking. How thankful I am that I was privileged for so long to hear my mother's words: words of affection and instruction, of explanation and comfort, of love and reassurance, of advice and humor — and of song. On Feb. 22, after 88 years, her quota of words was used up. I'll be recalling them, along with my mother's laughing face and melodious voice, for the rest of my days. What a blessing my mother's life was. May her memory be equally blessed.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

'From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic. . .'

Friday marked the 75th anniversary of one of the most important speeches in the history of postwar statesmanship, one that heralded the dawn of the Cold War and that for the first time extolled the unity of the world's English-speaking peoples as a distinct phenomenon in international affairs. The speech was delivered by the most famous and admired Englishman in the world, former Prime Minister Winston Churchill, at a venue almost no one had ever heard of: obscure Westminster College in tiny Fulton, Missouri. Churchill, a master craftsman with words, titled his speech "The Sinews of Peace." But that title never stuck. Instead, Churchill's remarks that day entered history as his "Iron Curtain" speech.

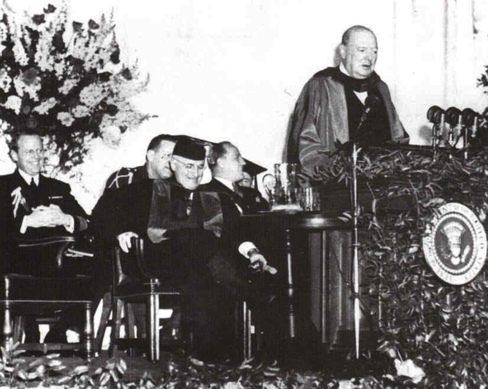

With President Truman at his side, Winston Churchill delivers his 'Iron Curtain' speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, March 5, 1946. |

Eight months earlier, in July 1945, Churchill's Conservative Party had suffered a stunning defeat at the polls, losing to Labor in a landslide. His brilliant wartime leadership notwithstanding, Churchill was replaced as prime minister by Clement Atlee. It was a painful loss, which Churchill bitingly described in his memoirs: "At the outset of this mighty battle, I acquired the chief power in the State, which henceforth I wielded in ever-growing measure for five years and three months of world war, at the end of which time, all our enemies having surrendered unconditionally or being about to do so, I was immediately dismissed by the British electorate from all further conduct of their affairs."

But if Churchill was out of office, he wasn't out of politics. Nor was he far from the public's mind, to judge from the torrent of speaking invitations he received from all over the world. Most of those requests, writes David Reynolds in the New Statesman, "elicited a polite 'no' from his secretaries."

An invitation to deliver the annual John Findlay Green Foundation Lectures at an obscure college in America's rural hinterland (worse still, a dry campus) would have received similar treatment, but for a P.S. scrawled at the bottom: "This is a wonderful school in my home state. Hope you can do it. I'll introduce you. Best regards – Harry S Truman."

The opportunity to deliver a speech with the president of the United States at his side was one Churchill could not pass up. Truman's presence, he knew, would guarantee maximum exposure for the speech, and he accepted the college's invitation at once. The president suggested that Churchill come to Washington first, so that they could travel together to Missouri by train. On March 4, 1946, Truman and the former prime minister, along with a few White House aides, boarded the presidential train for the 18-hour trip to Missouri.

The journey offered the two men their first real chance to get to know each other. "Truman insisted Churchill call him Harry; Churchill agreed with delight, insisting that the president call him Winston," recounted Paul Reid and William Manchester in The Last Lion, their magisterial biography of Britain's legendary leader.

Truman at first demurred, telling Churchill that given his importance to England, America, and the world, "I just don't know if I can do that." Churchill: "Yes you can. You must, or else I will not be able to call you Harry." Truman replied: "Well, if you put it that way, Winston, I will call you Winston."

. . . As the presidential train rolled past a cyclorama of sleeping towns and darkened farms, Churchill excused himself to work on his speech. . . . Truman . . . told Churchill he did not intend to read the final text so that he could tell reporters as much if they asked, which they surely would. But when Churchill emerged from his salon with the finished product, Truman could not resist. After reading it, he called it a "brilliant and admirable statement." As the president handed it back to Churchill, he predicted it would "create quite a stir."

So it did.

After amusing his Westminster College audience with a riff on their school's name ("The name "Westminster" is somehow familiar to me; I seem to have heard of it before"), Churchill got down to business:

The United States stands at this time at the pinnacle of world power. It is a solemn moment. . . .

The awful ruin of Europe, with all its vanished glories, and of large parts of Asia glares us in the eyes. When the designs of wicked men or the aggressive urge of mighty states dissolve over large areas the frame of civilized society, humble folk are confronted with difficulties with which they cannot cope. For them all is distorted, all is broken, even ground to pulp.

The "supreme task and duty" of America and its democratic allies, he said, was "to guard the homes of the common people from the horrors and miseries of another war" and to fearlessly proclaim "the great principles of freedom and the rights of man which are the joint inheritance of the English-speaking world."

Then came what Churchill called "the crux" of what he had come to say: his plea for "a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States." He pressed for much more than "growing friendship and mutual understanding" between Britain and America. There should be military cooperation and interchangeable weaponry, he proposed, as well as "the joint use of all naval and Air Force bases in the possession of either country all over the world," and ultimately even common citizenship.

Three times Churchill spoke of a "special relationship" between the United Kingdom and the United States. The phrase stuck. Over the next 75 years, it would be invoked again and again by American and British leaders to describe the unique bond that links the two nations. In a 1985 toast at the British embassy in Washington, for example, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declared: "There is a union of mind and purpose between our peoples which is remarkable and which makes our relationship a truly remarkable one. It is special. It just is." In his reply, President Ronald Reagan said that "the United States and the United Kingdom are bound together by inseparable ties of ancient history and present friendship." Such effusive expressions of kinship between the American and British nations are taken for granted now. But when Churchill first invoked the "special relationship" at Fulton, as Reynolds notes, it was a "consequential addition to the lexicon of international politics."

Then came an even more consequential addition, as Churchill turned to the menace posed by the Soviet Union.

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and, in many cases, increasing measure of control from Moscow. . . . The Communist parties, which were very small in all these Eastern states of Europe, have been raised to pre-eminence and power far beyond their numbers and are seeking everywhere to obtain totalitarian control. Police governments are prevailing in nearly every case, and so far, except in Czechoslovakia, there is no true democracy.

The Soviets didn't want to start a war, Churchill said. "What they desire is the fruits of war and the indefinite expansion of their power and doctrines." Only Anglo-American resolve could keep Moscow from steadily enlarging its sphere of influence — from extending that "iron curtain" — and bringing more and more of the globe under its boot. Churchill was not calling for military confrontation; he was urging the Western democracies to unite in order to deter Soviet expansionism. As noted, the title he had given his speech was "The Sinews of Peace." But as Reid and Manchester wrote, many interpreted his speech as dangerous saber-rattling:

The reaction was immediate, and not favorable. The Nation, a small, sober, left-wing magazine, said that Churchill had "added a sizable measure of poison to the already deteriorating relations between Russia and the Western powers," and added that Truman had been "remarkably inept" by giving Churchill the platform from which to administer his poison. The Wall Street Journal , echoing the isolationist mantra of earlier in the decade, rejected Churchill's call for an English-speaking alliance, saying that "the United State wants no alliance or anything that resembles an alliance with any other nation."

More furious by far was the reaction in Moscow. In an interview with Pravda, the Soviet dictator Josef Stalin lambasted Churchill, calling him a warmonger, a slanderer, and a racist on the order of Hitler. The former prime minister took the attack in stride, remarking mildly that he had had plenty of practice at shrugging off "harsh words . . . from the most powerful of dictators." All the same, Stalin's savage response confirmed the significance of the Fulton speech, and ensured that it would be remembered as one of the opening sorties of the Cold War.

Seventy-five years after it was delivered, Churchill's "Iron Curtain" address is as notable for its prescience as for its eloquence. He was right about the Soviet threat and about the long twilight struggle that was just getting underway between the Communist powers and the democracies of the West. Unlike Churchill's speeches during the bleakest days of World War II, his Fulton speech was not delivered "in defiance of bombers overhead," William Safire would write years later. Nonetheless, it remains "the most Churchillian of Churchill's speeches." When the Soviet Empire imploded 40-plus years later — when the nations of Eastern Europe broke from Moscow's grip, ousted their Communist regimes, and established democratic governments — the extraordinary changes were described everywhere as the fall of the Iron Curtain. By then Churchill was long gone. But there was no improving on the stark metaphor he had conjured that day in a small town in Missouri, just as the Cold War was dawning.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The last line

"But that is another tale, and as I said in the beginning, this is just a story meant to be read in bed in an old house on a rainy night." — John Cheever, Oh What a Paradise It Seems (1982)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter or on Parler.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.