On Christmas Eve in 1664, a London resident named Goodwoman Phillips was found dead in the run-down district of St. Giles-in-the-Fields. Telltale "buboes" on her corpse left no doubt about the cause of death. Her house was sealed and the words "Lord Have Mercy On Us" were painted on the door in red: Phillips had died of bubonic plague.

Only a few other deaths from plague were reported over the next few months. But by April, the numbers had begun to climb markedly. When summer arrived, death was everywhere. Records from mid-July showed 2,010 deaths, spread among every parish in London. The death toll a week later had jumped to 7,496. Over a period of 18 months, the Great Plague of London, as the epidemic came to be called, would claim more than 100,000 lives — roughly a quarter of the city's population.

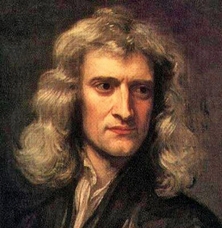

Then as now, social distancing was an important response to the deadly outbreak. Urban residents who could afford to do so fled to the countryside. Among the institutions that closed for the duration was Cambridge University, and among the students who headed home for what today we would call self-quarantining was a 23-year-old mathematics student by the name of Isaac Newton.

For the next year and a half, Newton remained at his family's farm in Lincolnshire, reading, studying, and thinking alone. While the bubonic plague raged elsewhere, Newton embarked on what he would later describe as the most intellectually productive period of his life. That long interval, from the summer of 1665 to the spring of 1667, might be described as the most intellectually productive period of any individual's life — ever.

One subject that had always interested Newton was light and color. Two years earlier, visiting the annual Sturbridge Fair near the university, he had purchased a small glass prism. He had been fascinated by the way the prism seemed to change white light into a spectrum of rainbow-like colors. No one understood where those colors came from; one theory was that the glass somehow added color to otherwise colorless light.

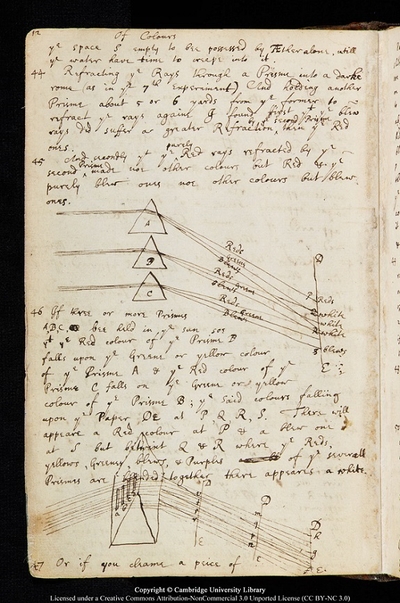

Newton decided to use his enforced absence from Cambridge to try and crack the mystery. Setting his prism in different positions as the sun streamed through his south-facing window, he carefully noted where the colors appeared on the wall across the room. He made detailed observations and measurements , and gradually came to understand that the prism was refracting — that is, bending — the sunlight, and in the process revealing its component colors. Newton had discovered that white light is a blend of every color in the rainbow, but that those colors become visible only when light rays are refracted at different angles.

All of modern optics builds upon Newton's discovery. It would be another seven years before he communicated his findings to anyone else, and nearly 40 years would elapse before he published his findings in book form. But the groundbreaking insights dated to those months of self-quarantine on a farm in Lincolnshire.

That wasn't all that occupied Newton's mind. He turned his attention to movement and inertia, and what was then the unsolved problem of how to measure the changing speed and direction of an object in flight. Shoot an arrow or fire a cannonball: They hurtle upward, then gradually slow, then change direction and plunge back down. But what determines their velocity and direction? This was a mystery no one had solved — until Newton focused his attention on the question of motion and how it was governed. Gradually he worked out the three essential laws that make motion comprehensible:

- A body at rest will remain at rest, and a body in motion will remain in motion, unless acted upon by an external force.

- The force acting on an object is equal to the mass of that object times its acceleration — or in mathematical notation, F = ma.

- For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Newton's laws laid the foundation for classical mechanics, and upon it generations of physicists would build towering edifices. The mathematics required to derive these laws — which involve multiple variables with continuously changing quantities — did not exist in Newton's day. So he invented an entirely new mathematical discipline. He called it his "method of fluxions," though eventually it would be known as differential calculus. (Independently, the German scholar Gottfried Leibniz would later develop it as well.) Without calculus, modern mathematics, engineering, and statistics would be impossible.

A page of Isaac Newton's notes on light and color, written during his annus mirabilis in 1665-66. |

Any of these achievements would have assured Newton's fame. But the heights he scaled during his months of isolation were greater still.

In his garden one day, an apple really did fall (or so he recalled as an old man decades later). The young university student pondered the force that pulled that apple to the earth. It was a force that seemed to operate even at great distances: An apple dropping from the highest tree imaginable would still hit the ground. How far out did this force reach? Perhaps all the way to the moon. Yet the moon didn't fall to the earth, but traveled around it instead. Why?

The problem of celestial movement vexed the intellectuals of Newton's day. They could envision a globe being swung on a chain, circling round and round, centripetal force holding it in a steady orbit. Cut the chain, however, and the circling stops — the globe flies off in a straight line. Yet heavenly bodies don't fly off in straight lines. Though untethered by chains, they move in fixed orbits. How could that be?

Alone in Lincolnshire, Newton solved the puzzle: Incredibly, he discovered the law of gravity. The same force that pulls an apple to the ground holds distant planets in their paths. That was the chain linking the moon to the earth and the planets to the sun. Gravity couldn't be seen or touched, but it could be proved with mathematics. He filled page after crowded page with his calculations, and eventually derived the formula that, he said, "allows me to explain the system of the world."

For nearly 20 years, Newton told no one of his discovery. When he finally published his great treatise on motion and gravitation — its title was Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Latin for Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy ) — the effect was seismic. Newton's discoveries, in the words of Alan Charles Kors, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, amounted to "one of the most extraordinary scientific syntheses in the history of the human mind."

The Principia is generally reckoned the most important book in the history of science. It jolted Western civilization to its core, for it demonstrated, as no prior work ever had, that the universe was lawful, logical, and knowable. To a deeply pious Europe, it meant that mere mortals could perceive the very blueprint of Creation. To study the world empirically, to understand its workings, was to come closer to the mind of God than had ever been thought possible. Newton's insights during the months of plague that kept him at home imposed a mathematical order to the universe that permanently closed the door on the age of magic, and opened the door to something even more wondrous: the triumph of modern science. That astonishingly fruitful period of "social distancing" came to be known as Newton's annus mirabilis — year of wonders.

Unlike so many who perished during the Great Plague of London, Newton lived a very long life. He was 84 when he died in 1727, and was interred with many honors in Westminster Abbey.

But his most famous epitaph was the couplet composed by Alexander Pope, the famed English poet:

"Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night,

God said, Let Newton be! — and all was light."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Does history smile on Biden's chances?

Barring the unforeseen, Joe Biden will be the Democratic nominee for president. But if history is a reliable guide, he is highly unlikely to be elected president.

So, at any rate, argues veteran political journalist Byron York in a recent Washington Examiner column . He focuses not on Biden's specific strengths or weaknesses vis-à-vis Donald Trump, but on the track record of presidential candidates with his political résumé — specifically, his 36 years in the Senate and two terms as vice president. Judging from the experience of other senators and vice presidents who have run for president, writes York, Biden's odds don't look good:

[T]he first reason Biden will not become president is that no one who served 36 years in the Senate has ever become president. No one who served 30 years in the Senate has ever become president. No one who served 25 years in the Senate has ever become president. No one who served 20 years in the Senate has ever become president. No one who served 15 years in the Senate has ever become president.

It's not for lack of trying. Bob Dole, who was sworn into the Senate on Jan. 3, 1969, ran for president 27 years later, in 1996. He quit the Senate during the campaign to show his determination to become president. But his long years in the Senate, plus his age — he was 73 at the time and the subject of endless suggestions that he was too old to be president — were a deal-killer for voters.

Others tried, too. In 2008, John McCain ran for president after 21 years in the Senate. It didn't work. In 2004, John Kerry ran for president after 19 years in the Senate. That didn't work, either.

A long career in the Senate is simply not a foundation for a successful run for the White House.

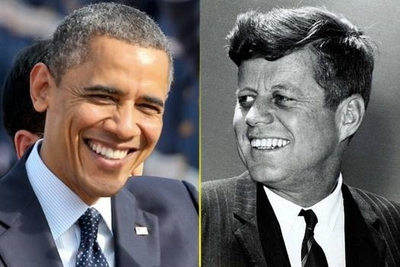

In the past 100 years, only three sitting senators have been elected president: Warren Harding in 1920, John F. Kennedy in 1960, and Barack Obama in 2008. Harding had spent just five years in the Senate, Kennedy eight, and Obama four. Biden's exceptionally long tenure, six full terms, strongly suggests that he is cut out to be a senator, writes York — not a president.

In the past 100 years, only three sitting senators have been elected president. The two most recent were Barack Obama and John F. Kennedy. |

Biden's eight-year run as Barack Obama's vice president might seem to give him an advantage in landing the top job; after all, nearly one-third of US presidents formerly served as veep. But there, too, historical precedent cuts against Biden's chances. Eliminate the vice presidents who ascended to the White House on the death or resignation of the chief executive, and eliminate those who were elected president while they were still serving as vice president, and what remains isn't encouraging:

Only one president has gone from the vice presidency to private life and then to the presidency. Richard Nixon served as vice president in the 1950s, narrowly lost the 1960 presidential election, and then came back to win the presidency in 1968. That is Biden's hope — that a vice president can leave office and then, after a period outside government, return to win the White House.

Perhaps. But Nixon, who spent less than three years in the Senate, became vice president a few days after turning 40 and was sworn in as president at 56 — more than two decades younger than Biden, who will be 78 on Inauguration Day, 2021.

Finally, there is what York, crediting the respected scholar and journalist Jonathan Rauch, identifies as the "14-Year Rule." It amounts to a sell-by date for politicians: Anyone who takes longer than 14 years to get from his first statewide victory (governor or senator) to a party's national ticket will not become president.

Biden didn't even get close. It took him 36 years to get from his first Senate victory to the vice presidency. If he wins the presidency now, it would be 47 years from that first Senate swearing-in until Inauguration Day.

It should go without saying (but I'll say it anyway): Such historical "laws" exist to be broken. Until 2016, no one had ever been elected president without previously holding high political office or military rank. Until 2008, no African American had ever been elected president. Before 1980, a divorced president was considered unthinkable. In theory, anything can happen in a presidential campaign. In theory.

As investors are constantly reminded, past performance is no guarantee of future returns. The same is true of campaigns for the White House. All the same: If you're planning to gamble on Biden's presidential prospect, history would recommend you hedge your bet.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The last line

"I shall conclude the account of this calamitous year therefore with a coarse but sincere stanza of my own, which I placed at the end of my ordinary memorandums the same year they were written:

A dreadful plague in London was

In the year sixty-five

Which swept an hundred thousand souls

Away; yet I alive!"

— Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year (1722)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter