IN THE RACE for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, Elizabeth Warren is the candidate I like least, so I'm shedding no tears over her dismal 4th-place finish in the Nevada caucuses. Having coming in third in the Iowa caucuses on Feb. 3 and fourth in the New Hampshire primary on Feb. 11, Warren's wretched showing in Nevada ought to mean lights out for her campaign, at least by historical standards. In the last 45 years, only one Democrat — Bill Clinton in 1992 — managed to win the nomination despite losing the first three caucus/primary contests. And Clinton, unlike Warren, came in second in New Hampshire. (With characteristic chutzpah, the Arkansas governor claimed that his decisive loss to Paul Tsongas had made him "the comeback kid" — and journalists swallowed it).

Warren's exceptionally weak showing in Nevada was all the more disappointing for her and her supporters because it came just after her exceptionally strong showing in the Las Vegas debate last Wednesday. Virtually every observer declared Warren the winner of that debate, and in the 24 hours following the debate her campaign raised more than $5 million. "Re-energized Warren Looks to Regain Support in NV and Beyond," trumpeted a RealClearPolitics headline.

Unfortunately for the Massachusetts senator, her "fiery " debate showing came after four days of early voting in Nevada had concluded. Nearly 75,000 Nevada Democrats filled out their caucus preference ballots between Feb. 15 and Feb. 18. None of those ballots, of course, was affected by Warren's success at the Feb. 19 debate. By the time the debate took place, more than two-thirds of the Nevada vote had already been cast. If there was a debate "bump" for Warren, it came too late to make any difference.

This is just the latest example of the folly of early-voting laws.

Over the past quarter-century, the option to vote in advance has become routine in American elections. Citizens in 41 states and the District of Columbia are allowed to cast ballots ahead of Election Day, either by mail or at early-voting polling stations. In some states, early voting commences a full 45 days before the official date of the election. Voters in California, which will hold its primary on March 3, have been submitting votes for three weeks already — as of Friday, according to CNN, more than 1.3 million vote-by-mail ballots had been returned. (Polling places open today, a week early, for the presidential primary in Massachusetts.)

Early-voting laws, which were supposed to increase participation in elections, have had the effect instead of reducing turnout. |

Early voting is promoted as a boon to democracy: a way to lift voter turnout and encourage more participation in the political process. In reality, it has been counterproductive: Instead of motivating more people to take part in elections, the evidence to date shows that early-voting laws actually decrease turnout . Paradoxical? Not really. By dragging out for weeks what used to be the concentrated, communal experience of a single decision day, researchers at the University of Wisconsin found, early voting winds up "dissipating the energy of Election Day" and "reducing the civic significance of elections for individuals." Like so many other innovations promoted by politicians, early voting laws have worsened the problem they were designed to ameliorate.

More serious than its effect on voter turnout, however, is the way early voting destroys informational equality.

Giving voters in primary and general elections 45 days in which to cast their ballot guarantees that many, perhaps most, of them will make their choice unaware of the late-breaking revelations that are common in political contests. Warren's commanding debate performance was only the most recent reminder that a campaign's last innings can often be the most illuminating — even game-changing.

"Just think of the revelation, days before the 2000 election, of George W. Bush's drunk-driving arrest," I wrote in a 2015 column. "Or John Silber's prickly interview with Natalie Jacobson as the 1990 Massachusetts governor's race neared its climax. Or Lyndon Johnson's bombing halt in North Vietnam on the eve of the razor-sharp election in 1968. Or Ross Perot's wild claim, late in the 1992 campaign, of his daughter's wedding being sabotaged by Republicans."

Early voters, in short, are more likely to make their choice with less information than voters who wait until Election Day — and more likely to regret not waiting. How many of the millions of early votes already cast for Super Tuesday's primaries were for Deval Patrick, Andrew Yang, or Michael Bennet, all of whom dropped out of the race after early voting began? How many voters plumped for candidates who looked a lot stronger 15 or 20 days ago than they do now?

Campaign operatives relish early-voting because it enables them to bank votes days or weeks before Election Day. But it's a two-edged sword, as Elizabeth Warren can now attest from personal experience. She and her surrogates urged supporters to vote early. She would almost certainly have done better in Nevada if she had urged them to wait.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Oscar Biscet, Cuban hero

Early Thursday morning, one of the most admirable human rights champions in the Americas was arrested by one of the worst dictatorships in the Americas.

News of the arrest was disseminated by Inspire America, a nonprofit foundation that promotes freedom and democratic reform in Cuba:

Thugs from Castro's secret police broke into the home of Dr. Oscar Elias Biscet and kidnapped him in front of his wife, Elsa Morejon. He was driven to an undisclosed location and released this afternoon.

Four police vehicles and two motorcycles remained parked outside of the home in Havana, while at least four regime officials searched the home, breaking many of its contents and confiscating computers and other items. After leaving, a contingent . . . returned, confiscated Mrs. Morejon's cell phones, and deleted accounts of the incident she had posted to her Twitter account.

Biscet, a 58-year-old Cuban physician who has been arrested dozens of times by Cuba's totalitarian regime and spent more than 12 years behind bars, is one of the country's great exponents of human dignity, liberty, and democracy. In the face of relentless intimidation and brutality by the Castro government, he has steadfastly spoken out in defense of decency and freedom, expressing many of the same truths articulated by Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., the Dalai Lama, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To the regime in Havana, that makes him a problem to be suppressed. So do his Christian faith and his black skin. But to people who care about freedom and who support nonviolent resistance to tyranny, he is a hero.

In 2007, Biscet was honored by George W. Bush with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The medal was awarded at a White House ceremony in absentia: At the time, Biscet was in a punishment cell in the Combinado del Este prison in Havana, where he was serving a prison sentence for criticizing Cuba's communist dictatorship. Peter Kirsanow, a member of the US Commission on Civil Rights, wrote at the time that the circumstances of Biscet's incarceration were like something out of a Victor Hugo novel:

[His cell is] windowless and suffocating, with wretched sanitary conditions. The stench seeping from the pit in the ground that serves as a toilet is intensified by being compressed into an unventilated cell only as wide as a broom closet — and not much longer.

Biscet's rarely permitted to leave this impossibly tiny cell that he somehow manages to share with a series of criminals who, it seems, are specifically selected by the authorities for violent tendencies, and who, Bisect maintains, are frequently incited by those authorities.

Biscet reportedly suffers from osteoarthritis, ulcers, and hypertension. His teeth, those that haven't fallen out, are rotted and infected. Water, if you can call it that, is at a premium. Prisoners often are forced to wash themselves and their clothing in water filled with feces and urine. Yet Biscet's permitted no medicines or toiletries. Nor is he allowed any communication with the outside world. He gets no newspapers. He can receive no visitors — not even doctors or clergy. Even his wife has only seen him fleetingly a few times over the last four years.

Eventually Biscet was released and — during the thaw in US-Cuban relations at the time of Barack Obama's 2016 visit to the island — permitted to fly to America. (He visited Bush at the former president's office in Dallas, and received his award in person.) But he never considered abandoning his homeland. He returned to Cuba after his brief American sojourn, and picked up right where he had left off.

Why isn't a great soul like Biscet as well known in the free world as someone like Nelson Mandela was? (In 2011, Biscet told an interviewer that he wished all "free and civilized countries would boycott Cuba, the way they did racist South Africa.") For that matter, why aren't the names of courageous dissidents in China, Iran, and North Korea known and celebrated in the West? How is it possible that a leading candidate for US president isn't disqualified by his long history of praising communist dictatorships? Why do men and women who aspire to be the "leader of the free world," never say a word about the bravest human rights defenders on earth?

Why have so many American journalists and celebrities been so eager for so long to rhapsodize about the supposed paradise of the Cuban revolution, ignoring the mountains of evidence that it is really a tropical dungeon? Why do Americans, born and reared in freedom, not know more about the slavery in which so many of their fellow human beings are forced to live? Why is Bernie Sanders still parroting the same propaganda that Castro acolytes were spouting at the height of the Cold War?

One day Cuba will be free. Then Oscar Elias Biscet will take his place among the nation's nobility. In Cuba, as in all dictatorships, it is the dissenters who sustain hope and keep conscience alive. They are the bravest and the best people on the island, even if most Americans have never even heard their names.

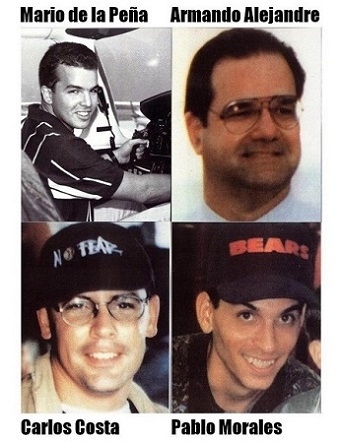

POSTSCRIPT: On this date 24 years ago, Armando Alejandre, Carlos Costa, Mario de la Peña, and Pablo Morales were murdered in cold blood by the regime of Fidel Castro. Three of the men were US citizens; one was a legal permanent US resident. They were members of Brothers to the Rescue, flying over the Florida Straits in a pair of blue-and-white Cessna 337s, as they often did in the hope of saving lives. They were scouring the sea for anyone who might be fleeing Cuba in makeshift rafts or flimsy inner tubes, in order to drop food and bottled water to the refugees, and to radio their location to the Coast Guard. Though the four were flying well north of Cuban territorial waters, Castro's air force, without warning or reason, scrambled two MiG fighters and blew the rescue planes out of the sky. The little Cessnas and their unarmed civilian passengers were disintegrated. Only a large oil slick marked the spot where they went down. No bodies were ever recovered. The United States has never avenged their deaths.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

How bike lanes kill

As regular readers may know, I'm no fan of the relentless push in many towns — including the ones I live and work in — to make the streets more and more friendly to bicycles by making them less and less friendly to automobiles. I have nothing against bicycles, which are nimble, nonpolluting, healthful, and inexpensive. I also have nothing against rollerblades, Segways, wheelchairs, scooters, unicycles, or horse-drawn buggies. But none of them belong in the middle of crowded urban traffic.

Designated lanes for bicycles are a fine idea — where traffic is minimal or there is ample room to expand roadways. But the current mania for subtracting or narrowing already-crowded car lanes in order to benefit cyclists is terrible.

Inserting bike lanes into city streets disadvantages the overwhelming majority of drivers and passengers who rely on automobiles in order to accommodate the relatively tiny minority who bike. In a column last year I wrote: "The doctrine that cars, buses, and trucks should 'share the road' with bicycles sounds egalitarian and green, but it's as impractical as expecting motor vehicles to 'share' urban thoroughfares with skateboards and strollers. The chief function of those roads is to keep people and goods moving as rapidly, efficiently, and safely as possible. Bike lanes unavoidably impede that function — often to the detriment of bike riders themselves."

But taking away road lanes from cars in order to provide more lanes for bicycles isn't just inconvenient. It's also deadly, as Gary M. Galles, a professor of economics at Pepperdine University, shows in a recent essay for the Foundation for Economic Education.

He begins by noting that in the wake of implementing a new plan to bring down the number of people killed in Los Angeles traffic, the number of people killed in Los Angeles traffic went up:

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti created Vision Zero in 2015 in an effort to reduce non-driver traffic fatalities, especially pedestrian deaths. Its goals were to cut non-driver fatalities by 20% by 2015, 50% by this year, and 100% by 2025. Following that vision, the City Council adopted Mobility Plan 2035, a 20-year initiative to remove automobile lanes and make more room for bus and bike lanes to upgrade pedestrian and cyclist safety.

Results to date? Since Vision Zero was launched in 2015, according to the Los Angeles Times, the number of pedestrians, vehicle occupants, bicycle riders, and motorcyclists killed each year in crashes has risen 33%. (Fatalities surged in 2016 from 183 to 253, a 38% increase, and have dipped slightly since then.).

It isn't hard to understand why cramming Los Angeles drivers into fewer driving lanes makes LA's roads more dangerous, not less. And with the city planning to double down on its approach — a blueprint just approved by City Council would remove even more traffic lanes in order to make more room for bikes and buses — it seems obvious that congestion will only grow worse and fatal accidents more frequent.

Until reading Galles's essay, though, it hadn't occurred to me that there is another way in which increased congestion will cost lives. "More motor vehicles trapped in gridlock," he writes, "cannot clear the way for ambulances or fire trucks responding to emergency calls."

I tend to be skeptical of the "adopt-my-policy-or-people-will-die" school of analysis, but there is nothing theoretical about the outcomes to be expected when emergency response times slow down. When it takes EMTs longer to reach people suffering a heart attack, or becomes more difficult for fire trucks to reach a blazing building, the cost is paid in human lives. Galles quotes the Mayo Clinic's Roger White, an expert in the treatment of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: "A one-minute decrease in the call-to-shock time increases the odds of survival by 57%," White told USA Today, while decreasing the response time by three minutes "improves a victim's chance of surviving almost fourfold."

Even backers of the new Los Angeles transportation plan agree that it will worsen traffic in many parts of the city. That is another way of saying that emergencies will be responded to more slowly. And that is another way of saying that more victims of heart attack (or a stroke or ingested poison or a shooting or a fire) won't make it.

The numbers are jolting. If transportation economist Randal O'Toole is correct, for every pedestrian whose life might be saved by so-called traffic calming — i.e., by policies that deliberately slow automobile traffic in order to boost bikes and buses — more than 30 lives are apt to be lost due to delayed paramedics and firefighters. When Ronald Bowman, a scientist with the National Bureau of Standards, crunched the data for a plan to slow traffic in Boulder, Colo., he came up with an even more lopsided risk factor: 85 lives lost for each life saved.

To the militant and self-righteous bicycle lobby, of course, little of this matters. They want more bike lanes and fewer cars, they want them now, and they can be counted on to browbeat any objectors with loud insults and vehement sanctimony. But the objections are valid, whether or not they're heeded. Bikes are terrific, but they don't belong on the busiest city streets. The price of insisting otherwise isn't cheap.

Enjoy reading Arguable? Please tweet a thumbs-up to your followers!

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter