"It's time for states to ban lottery advertising." So declares journalist/scholar Howard Husock in the current issue of City Journal, the flagship publication of the Manhattan Institute. I enthusiastically second the motion.

The list of state programs that ought to be defunded is a long one, but few are more indefensible than the $600 million states pour each year into ads that promote government-operated gambling. "The spread of lotteries has played a leading role in the normalization of gambling, once considered a vice akin to drug use or prostitution," writes Husock, "and lottery sales are boosted by publicly funded advertising campaigns that prey on the weakness of gambling addicts, while encouraging non-gamblers to get involved, too."

My own attitude toward government and gambling is straightforwardly libertarian: I think gambling should be perfectly legal among consenting adults. And I think it should be absolutely barred on the part of government.

If it were up to me, private entrepreneurs would be free to offer any type of gaming opportunities (casinos, sports betting, online poker, lotteries) on roughly the same terms that apply to owners of building contractors, restaurants, manufacturing plants, or accounting firms — i.e., they would be regulated by the state to ensure compliance with standard safety, wage-and-hour, antidiscrimination, anti-fraud, and environmental laws, but would otherwise be free to use their own judgment in catering to their customers. Like any profit-making business, they would pay taxes. But they would be in competition only with other private gambling firms, because state-run lotteries would not exist.

State lottery agencies spend $600 million a year to coax citizens to take risks they are virtually guaranteed to lose. |

Today, alas, my libertarian scenario is pure fantasy. The governments of 45 states operate their own lotteries. Nearly all of them also participate in interstate gambling games like Powerball. State governments reap some $80 billion from these lotteries, accounting for 2% of overall state revenues. The likelihood of any state giving up those gambling dollars is pretty close to nil.

But while state-operated games of chance are bad, the use of taxpayer funds to advertise those games is immoral and atrocious. Such advertising depends almost entirely on coaxing citizens to take risks they are virtually guaranteed to lose. Lottery ads appeal especially to the poor and vulnerable, luring them with deceptive promises of riches and ease they have almost no chance of winning.

Husock points out that state lotteries can get away with such deceptive ads because they are exempt from Federal Trade Commission truth-in-advertising regulations. He quotes Andrew Clott, an expert in consumer law:

If the lottery were run purely by private industry instead of by state governments, it is likely the FTC guidelines would prohibit much of the current lottery advertising. Without this baseline of protection, consumers fall prey to sophisticated, deceptive marketing strategies which are backed by massive financial resources.

States shouldn't be in the gaming business at all. But if they are going to sell lottery tickets, they should do so without advertising the fact. Luring citizens — especially lower-income citizens — to gamble away their earnings is reprehensible. We would never tolerate the use of government funds to urge more people to drink alcohol, smoke marijuana, or view pornography. Those may all be legal activities, but they are also harmful to many people, and there is no legitimate government interest in actively promoting them. Lotteries are no different. Some 10 million Americans suffer from gambling addiction, and the last thing state funds should be spent on is enticing them to indulge their weakness.

Gambling doesn't require advertising, as the long history of under-the-table, yet highly profitable, numbers rackets attests. Indeed, there is no correlation between the profits states reap from lotteries and the dollars they spend to promote them. Massachusetts slashed its lottery ad spending "in the early to mid-1990s," the Pioneer Institute observes, "and yet, profits during this time continued to increase substantially."

Lottery advertising is an indecent use of public funds. In a free society, adults have the right to pursue their vices. But the government shouldn't spend their money to coax them into doing it.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The unloved color

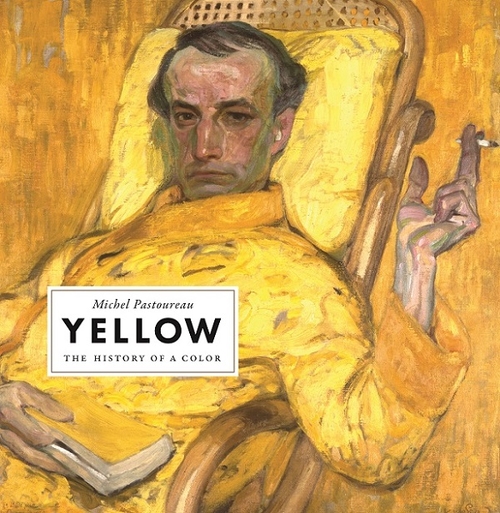

The colors of the Christmas season are red and green, but for the last few days, courtesy of the French historian Michel Pastoureau, I have been luxuriating in visions of yellow. In his latest book, Yellow: The History of a Color , Pastoureau tells the story of this most ambivalent of colors, one that in ancient times was associated with so much that was good in life — gold, sunshine, honey, grain — but which in recent centuries acquired more disturbing and disreputable connotations.

Of all the primary colors, yellow is the least popular. When respondents are asked by pollsters to name their favorite color, blue always comes in first by a wide margin and yellow always comes last. Such surveys have been conducted since at least the late 19th century, Pastoureau notes, and nothing seems to alter the results — neither geography, nor history, nor culture, nor sex.

That wouldn't always have been the case. Yellow was much admired in ancient Egypt, where it was linked to Ra, the sun god, and it evoked similar positive meanings in pagan Greece, where deities were often depicted with golden-yellow hair, chariots, and dress. Yellow enjoyed a vogue among upper-class Florentine women in the early 14th century, and it was particularly favored by King Henry VIII of England. In fact, writes Pastoureau, Henry liked yellow so much that he wore outfits prominently featuring that shade each time he remarried "and demanded that the new queen and all the court wear it as well."

But for most of the past millennium, yellow has been a disfavored color, for reasons bodily, religious, and political.

To medieval physicians, it was significant that yellow was the color of urine and bile. Whereas red and green indicated good health and youthful vigor, Pastoureau explains, yellow was connected with "decline, desiccation, aging." It was "a barren, dull, withered, and more or less faded color," and its symbolism became increasingly negative.

By the late Middle Ages, Christian art routinely depicted Judas, the apostle who betrayed Jesus, wearing a yellow robe. Images celebrating the triumph of the Church frequently used yellow to portray Jews and the synagogue. In 1269, King Louis IX of France — later canonized as Saint Louis — issued an edict ordering all Jews in his realm to wear a yellow badge in order that they "be recognized and distinguished from Christians." At various times, other outcast groups — lepers, prostitutes, and thieves, among others — were also required to wear such humiliating insignia. Centuries later, of course, Nazi Germany would impose the yellow star on European Jews as a prelude to extermination.

In the modern era, yellow retains its negative aura. "A man would never wear yellow unless he wanted to draw attention to himself or deliberately transgress social codes," writes Patourneau. In theater posters and political cartoons, artists "made yellow the color of both the deceivers and the deceived." It was also the color of sadness and abandonment: In Edward Hopper's 1927 famous painting The Automat , a woman sits in a lonely cafeteria, dejectedly drinking a cup of coffee. She wears a stylish yellow hat, but far from dispelling the scene's melancholy mood, it only intensifies it.

Yellow: The History of a Color is the fifth such volume that Pastoureau has produced. Like its predecessors, which recount the visual and cultural histories of blue (2001), black (2009), green (2013), and red (2017), this one is elegant and engaging — as alluring to gaze at as it is compelling to read. Yellow may be an unsettling color, but this is a lovely and striking book.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

ICYMI

In my Sunday column , I wrote about the corrosive contempt that has become such a ubiquitous feature of contemporary American politics. Obviously sharp elbows and tongues have always been a part of hard-fought campaigns. But candidates and activists today are no longer content to express vehement disagreement with their opponents. Increasingly they see those on the other side of the political divide not as fellow Americans with whom they differ, but as "deplorables" or "losers " whom they despise. More than any time since the Civil War, the United States is in need of a respected leader to take a stand against a spreading culture of contempt. But where is such a person to be found?

Enjoy reading Arguable? Please tweet a thumbs-up to your followers!

The last line

"Tho' I've belted you and flayed you,

By the Livin' Gawd that made you,

You're a better man than I am, Gunga Din!" — Rudyard Kipling, "Gunga Din" (1890)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter