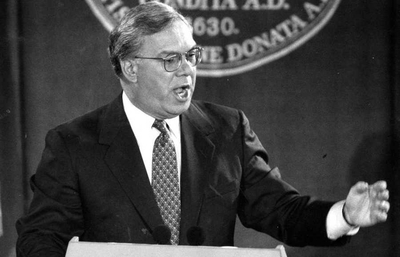

IT SNOWED in Boston on April 1, and Mayor Menino couldn't manage to get the streets cleared. Not because the snowstorm was a surprise — meteorologists had forecast it two days in advance. Not because the mayor was short-handed — he had a fleet of snowplows and an army of public-works employees at his command. Not because the city's snow-removal budget was depleted — by New England standards, it had been (up to April 1) a very mild winter. Not even because the post-blizzard weather made cleanup impossible — no sooner did the snow end than the sun came out and temperatures rose to the 50s.

So why couldn't the mayor manage to clear the streets? Don't ask him. The best he could come up with was: "We're trying to figure out what's wrong." (He also hinted darkly that "somebody" was trying to make him look bad.) But what was there to figure out? City Hall screwed up again, that's all. The bureaucrats bungled another one. The mayor — who styles himself the "CEO of a $1.5 billion corporation" — merely proved anew that when the government is in charge of doing a job, it can be trusted to do it badly.

Tom Menino would have trouble running a hardware store. It's preposterous to imagine that he can outline Boston's development for the next 33 years. |

But Menino is undaunted. This week he formally launched a massive exercise in municipal control called "Boston 400." Its purpose: "To develop a comprehensive plan for the city's growth — a list of everything we want to achieve by the year 2030." The mayor may not know what to do when it snows, but he intends to dictate the future of Boston's physical development for the next third of a century.

Menino and his central-planning politburo, the Boston Redevelopment Authority, are selling Boston 400 as a kind of old-fashioned New England town meeting writ large. There are to be committees and subcommittees, public gatherings and forums. They speak reassuringly of "neighborhoods" and "outreach" and "broad representation." The mayor promises to "involve people from all over the city" and to "give everyone a seat at the table."

But the "outreach" is for show. Boston 400 will be an exercise of insider clout and political power. The government will decide how Boston should develop. The government will decide where money should be spent. The government will decide which industries to promote. The government will decide how to change Boston's skyline, Boston's waterfront, Boston's subways, Boston's parks.

Nowhere in Menino's speeches or writings about Boston 400, and nowhere in the documents released by the BRA, do the words "freedom" or "individual" or "choice" appear. Yet what could matter more? Cities don't become great (or remain great) because vast committees of bureaucrats order them to. Urban vitality doesn't spring from the bowels of City Hall. It comes from the imagination of entrepreneurs, the vision of private landowners, the risk-taking of developers, the insights of newcomers.

It exaggerates the case only slightly to say that nearly everything that is enjoyable, wonderful, or successful about Boston came about through private initiative, while much that is ugly or distasteful is the fruit of politics. It was no task force of government hacks that created Trinity Church or the Arnold Arboretum or Filene's Basement or the Charles River Esplanade. It wasn't a mayoral task force that filled Boston with universities and hospitals and writers, that dreamed of reviving Faneuil Hall Marketplace, that kissed Fenway Park with magic, that raised the Bunker Hill Monument.

But — who sent the bulldozers into the old West End and wiped out a living neighborhood? Who let the Freedom Trail fall into scandalous disrepair? Who decided that a hideous elevated highway ripping through the heart of the Financial District was just what the city needed? Whose brilliant idea was it to turn the Charlesgate — a jewel in Frederick Law Olmsted's Emerald Necklace — into a cesspool? Who gets credit for the fascist wasteland of City Hall Plaza, or the concrete dreariness of Franklin Park Zoo, or the debt-ridden incompetence of the Hynes Convention Center?

Government drones, political operatives, central planners: Take a bow.

Menino would have his hands full running a hardware store. It is absurd to think that a mayor who can't clean up after a snowstorm is going to devise — in his words — "a sweeping blueprint for the city's future?" Boston doesn't need a mayor who will play God with its next 33 years. It needs one who can fix the city's public high schools, most of which are expensive, dilapidated failures. It needs one who can lower the staggering costs of doing business in Boston. It needs one who can make it safe to jog across Boston Common at night.

Boston 400 is built on a foundation of government-knows-best. But Boston was built on a foundation of private endeavor and individual liberty. It is not for the mayor and his cronies to micromanage Boston's growth or to decree what the city should look like in 2030. They are sure to guess wrong anyway.

If Mayor Menino wants to enrich generations of Bostonians yet unborn, let him bequeath them a government that knows its limitations — a government that doesn't interfere with the workers and thinkers who get things done. The recipe for Boston's future is free minds, free enterprise, and the free play of ideas. It will turn out best if City Hall isn't second-guessing every step.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter