For one brief shining moment last year, Boston Mayor Tom Menino had a great idea.

To help breathe life into some of the city's most blighted neighborhoods, he proposed a dramatic package of tax relief, whose centerpiece would be the abolition of sales taxes within the depressed areas. For Roxbury, Mattapan, and the grimmer parts of Dorchester – where today you can drive for miles and never see a supermarket, a department store, a theater, an auto dealer, a bookshop – it would be hard to imagine a more undiluted blessing.

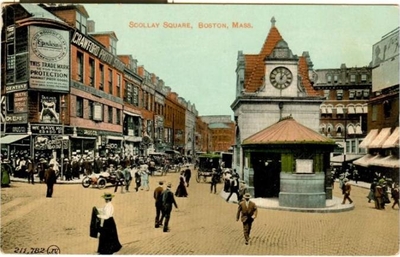

Boston's Scollay Square was a living, energetic hub . . . |

Freeing buyers and sellers to do business without having the government take a cut of every transaction would be a shot of urban growth hormone. The Massachusetts sales tax covers everything from margarine to minivans and makes every purchase one-20th more expensive than it should be. Wipe it out and vendors would stream in, lured by the prospect of higher profits and new market share. Customers would be offered more choices and lower prices. Local go-getters would scrape together the money to start new businesses. Retail chains would see windows of opportunity where before they had seen only dead ends.

It was not to be. Not here, not in Taxachusetts. Michael Dukakis may no longer be governor, but his philosophy of tax relief – he said it was fit only for "gutless wonders" – still dominates Boston.

That is why the Massachusetts tax burden is still among the 10 heaviest in America. It's why Massachusetts, alone among the states, continues to tax nonsalary income at a staggering 12 percent. It's why businesses in Massachusetts are socked with an outlandish 9.5 percent corporate income tax.

And it's why Menino's prescription to stop taxing struggling neighborhoods promptly vanished down the memory hole. He gave it only a fleeting, one-sentence mention in his State of the City Address on January 14, and dropped it entirely from his heavily hyped speech to the Boston Municipal Research Bureau on January 30.

So what else is new? When it comes to governance, Boston always lags behind. Elsewhere political leaders embrace tax relief as a spur to growth; here they fear it. In New York, Mayor Rudy Giuliani just quarterbacked a seven-day trial suspension of his city's 8.25 percent sales tax on clothing and shoes. The results were astounding. According to New York's Economic Development Corporation, apparel sales skyrocketed 94 percent during the one-week tax holiday. Eliminating the tax permanently, it estimated, would generate 17,000 new jobs. In the words of Bill Praschil, general manager of the Sears in Staten Island, the tax break "was awesome-wonderful-incredible."

. . . before government planners turned it into the lifeless wasteland of City Hall Plaza. |

A tax break in Boston would be awesome-wonderful-incredible, too. So, for that matter, would a regulation break. In a new study, the Institute for Justice (a Washington-based legal foundation that promotes entrepreneurial opportunity) concludes that "Boston operates on the principle that more is better: more regulations, more separate requirements, more fees, more agencies reviewing an application, more hearings, more paperwork." To start a business in Boston means fighting "a convoluted, onerous, and expensive regulatory process" – one that works particular hardship on "those outside the economic mainstream."

But instead of leading a drive to cut taxes and free more capital for private investment, Menino is demanding that a billion tax dollars be siphoned to build a government-run convention center. "Dare," he says, "to imagine the possibilities!"

Instead of taking a scalpel to the city's stifling bureaucracy, he proposes moving a chunk of the city's bureaucracy into the Ruggles Building in Roxbury. "We'll be able to lure investors after us," he promises.

Instead of letting this 366-year-old city grow naturally, free of top-down controls and government micromeddling, he wants a giant committee to decide how Boston should look in 2030. This, he breathes, is "the work of our lifetimes."

They never learn.

A new convention hall? Boston already has a state-run convention center. It was put up at a cost way over budget, it loses millions of dollars each year, and it has an indelible reputation for mismanagment.

The Ruggles Building? The state spent millions to get it built, millions more to "lease" it for the Registry of Motor Vehicles, and still more millions to evacuate it when poisonous fumes made it uninhabitable.

A master plan for Boston? Another one? The wretched master plan that bulldozed the West End wasn't bad enough? Or the master plan that turned the living Scollay Square into the dead wasteland of City Hall Plaza? Or the master plan that shoved the ugly Central Artery through the city's heart, exiling the North End and severing Boston from its waterfront?

Death to master plans. Death to politicians-know-best directives from on high. Politicians didn't make Boston a shipping power in the 18th century; bureaucrats didn't make it a medical mecca in the 20th. Private individuals did, risk-takers and visionaries who followed their blueprints, not master plans generated by City Hall or the State House.

If Tom Menino loves this city and wants to see it thrive, let him liberate it from the crushing weight of high taxes and the entangling snarl of red tape. Boston needs no more government buildings. What it craves is economic freedom, and the more the better.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Join the Fans of Jeff Jacoby on Facebook.