THE COHEN BROTHERS, Avi and Jacob, were ecstatic. Senator Orrin Hatch had just polished off a plate of their baklava and pronounced it the best he'd ever tasted. From the looks on their faces, you'd have thought the Prophet Elijah himself had just materialized in the non-smoking section.

President Clinton may have journeyed to the North End to sample the cannoli at Mike's Pastry a week earlier, but then, there was an enthusiastic throng of voters to greet him when he got there. What on earth was the senior senator from Utah doing at a nearly-empty Cafe Shiraz, a kosher restaurant in Brighton run by two young Iranian immigrants?

Senators Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) share a joke during an interview with the Deseret News in January 1990. |

Hatch, a devout Mormon and conservative Republican, was in Boston to speak ay a dinner for Chabad House, the outreach wing of the Lubavitch Hasidim, an orthodox Jewish movement. The hours before his speech he filled with small groups of Jewish business and religious leaders — he looking for financial support, they eager to develop a new DC connection.

And the link joining such utterly different species? No link. "I came because I was invited," Hatch explains to me, explaining nothing.

Politics makes odd bedfellows, they say. Meaning: In political life, you do deals with all kinds of people. Your foe today is your ally tomorrow.

But does "odd bedfellows" — a surprisingly intimate term, when you think about it, to describe relationships forged in the unromantic trade of politics — go beyond business?

Orrin Hatch's world may be parsecs away from that of Lubavitch hasidim and Jewish small-business owners, but he wasn't putting on an act last week. He was enjoying himself. He actually liked these guys, not one of whom will ever come within 500 miles of a Utah voting booth. To watch Hatch happily munching Middle Eastern food in a restaurant along a dreary stretch of Commonwealth Avenue was to watch someone much warmer and gentler than the inquisitor who bore down on Anita Hill so insistently during the Clarence Thomas hearings in 1991. It was to watch someone rather — appealing.

Incongruous: The Mormon from Salt Lake City schmoozing with the Jews from Brookline. But that's nothing. For real incongruity, listen to Hatch describe his friendship with that archliberal Democrat, Ted Kennedy.

"We're the Odd Couple," he recites, and it's obvious he gets a kick out of talking about it. "He's liberal, I'm conservative. He's Democrat, I'm Republican. He's from the East, I'm from the West. He's wealthy, I'm poor. . .

"He's like a brother to me."

The mind boggles. Sure, Ted may be okay in a sort of boozy, jovial way — but "like a brother" to the earnest, buttoned-down, very-well-behaved Hatch, a man who, for religious reasons, doesn't drink coffee?

"On lifestyles," he agrees, "we're probably totally different." No kidding.

But maybe that's the explanation. Maybe it's precisely when two colleagues are "totally different" — in outlook, in philosophy, in lifestyle, in background — that the hardiest friendships can grow. When a pair of pols are so wholly, irremediably unalike that there's not the slightest chance of either ever converting the other, there's no need to waste time trying. Agree at the outset that you'll disagree on virtually everything, and you've saved a lot of energy.

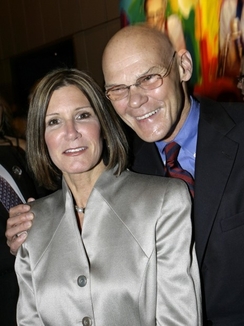

Odd couplings. It worked for Felix and Oscar. It works for Kennedy and Hatch. It seems to work spectacularly for Washington's oddest couple, Clinton guru James Carville and Republican strategist Mary Matalin.

As Hatch was giving his speech to the Lubavitch hasidim in Boston that evening, an eminent Canadian was dining at the home of Canada's consul-general in Weston. Former Prime Minister Joe Clark, about to leave public life after 21 years in office, was ruminating after a good meal and a couple glasses of wine about power, politics, and personalities.

Talk about opposites attracting: Republican political strategist Mary Matalin and Democratic Party guru James Carville have been married since 1993. |

How, he was asked, did he feel these days about Brian Mulroney, the current premier? (In a 1983 battle, Mulroney wrestled the Conservative Party leadership away from Clark; when Mulroney became prime minister soon after, he brought Clark into his Cabinet, first as foreign minister, then as constitutional minister).

"I respect him," Clark says, slowly. "I admire what he's done. We've worked very well together."

But do you like him? After working together for nine years, are you friends?

"No," he answers quietly, eyes fixed on the tablecloth. "We're not friends. I can't say we ever became friends."

Joe Clark and Brian Mulroney share far more common ground than Ted Kennedy and Orrin Hatch ever will. Who knows? Maybe if they agreed with each other less, they could have learned to like each other more.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter