WHEN LAST WE HEARD from Nathan McCall, he was joyfully beating an innocent white kid to a pulp.

"We all took off after him," he wrote on the first page of his 1994 memoir Makes Me Wanna Holler: A Young Black Man in America

Stomped him and kicked him . . . kicked him in the head and face and watched the blood gush from his mouth . . . kicked him in the stomach and nuts, where I knew it would hurt. . . . Every time I drove my foot into his balls, I felt better. . . . We bloodied him so badly. . . . We walked away, laughing, boasting. . . . Fucking up white boys like that made us feel good inside.

From that chest-thumping start, McCall went on to describe a youth brimming with violent crime. By his own (mostly unrepentant) reckoning, he is guilty of repeated acts of assault and battery, breaking and entering, assault with a deadly weapon, armed robbery, and attempted murder.

And rape -- lots of rapes. Especially gang rapes. Especially of very young girls. In fearsome detail, McCall recounted the first "train" he took part in -- a mass-raping of a frightened 13-year-old virgin named Vanessa. "After that first train," he bragged, "we perfected the art of luring babes into those kinds of traps. We ran a train at my house when my parents were away. We ran many at Bimbo's crib because both his parents worked. And we set one up at Lep's place and even let his little brother get in on it. He couldn't have been more than eight or nine." McCall's elaborate criminal history notwithstanding, he spent very little time behind bars: He did a total of eight days for shooting a man in the chest at point-blank range and served less than three years of a 12-year sentence for holding up a McDonald's. There was no punishment for all the homes he broke into, for all the victims he mugged, for all the people he shot, for all the girls he raped. Instead, McCall went from prison to a state university, and from there to a career in journalism that eventually landed him on the Metro desk of the Washington Post.

And on the bestseller list: Makes Me Wanna Holler drew rave reviews and sold a lot of copies. McCall is an unfiltered racist, he is given to self-pity, and he ought to be serving a life term in prison -- but he knows how to tell a story. Holler was a gripping and fiery read.

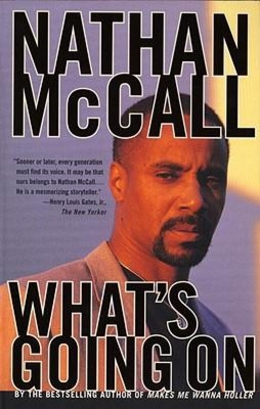

Now McCall is back with What's Going On, a slim volume of personal essays -- "my little truths," he calls them -- about "some of the issues that divide people and keep us racially polarized."

McCall's truths are little indeed, and most of them, come to think of it, aren't true. If they were written with the verve and drive of his first book, they might be worth reading nevertheless But What's Going On is verveless and driveless. Worse, it's boring. It is page after page of banal commentary and tiresome, trite conclusions

Here is McCall on encountering a playful white toddler (and his anxious mother) in a fast-food restaurant:

I have a theory about this sort of thing. I suspect that babies secretly plot to make fun of grown-ups when we behave in childish ways I think babies deliberately draw black adults and white adults into awkward racial predicaments. Then, they sit back and watch us squirm -- maybe that's why babies smile so much.

And here he is on the gentrification of Old Town in Alexandria, Virginia:

Old Towns symbolize the American way: America takes what it wants. Of course, that's not in keeping with the myth of this country, but it certainly reflects its practice -- here and throughout the world. When white folks "discovered" America, it already belonged to somebody else. Whites decided they wanted it, so they took it. Now they feel perfectly justified in treating everyone else like intruders. America, they shout pompously, love it, or leave it.

And on death:

The death of family members of friends is always a bummer. It's so depressing you sometimes forget that death may have meaning and purpose.

McCall's lame essays offer no reasoned argument, no shrewd insight, no compelling new theory. And no moving prose: There is scarcely an affecting paragraph in the book. He serves up an insipid blend of Rainbow Coalition and Nation of Islam, but without Jesse's pumping oratory or Farrakhan's (deranged) flair.

Hoping, perhaps, to capture some of the immediacy that helped make his first book so compelling, McCall sprinkles this one with raw details and street argot. But language that adds vividness to a memoir can be clangingly awkward in an essay. What McCall ends up with is not immediacy, but mere schoolboy crudeness:

He was pitch-black, had big, bulging eyes, a little pea-size head, and hair that looked like mice titties.

The bottom line [of John Wayne-style movies] was obvious. It was about pussy. The conqueror got the pretty girl.

[We] called him Itchy Booty because somebody once caught him scratching the crack of his behind, scratching hard and deep.

The one constant in McCall's writing is his pervasive anti-white racism. What's Going On is suffused with it. In McCall's blinkered view, politicians don't simply pander to voters -- they seek "to appease a childishly selfish white America." Muhammad Ali didn't just resist the draft in 1967 -- he "bucked white folks and refused to go to war." That wasn't yuppification going on in Alexandria, it was "the white takeover of black Old Town."

Nor can McCall criticize self-destructive behavior by blacks without adding a racist jab. "Some gangsta rappers," he writes, "are. . . no better than the drug dealer, the pimp -- or the wicked white man who earns his riches exploiting blacks." And while he can denounce the ugly messages violent rappets pump out, whites can't. "That's why Bill Bennett looks and sounds so out of place," McCall writes dismissively, "when he jumps into press conferences with C. DeLores Tucker."

Finally there is McCall's hypocrisy.

Repeatedly, he vilifies "paranoid" whites who fear young black males. He is "disgusted" by them -- "pissed off" by their suspicions that "we might . . . break into their houses and rip off their TVs." He moved from a mostly white Virginia suburb to the mostly black Maryland enclave of Prince George's County, he says, so he would be able to "step outdoors without worrying about being insulted by some arrogant white dude who thinks I'm after his wallet" or see "some old, blue-haired white lady clutching her bags when she sees me."

Needless to say, the fear some whites feel when they encounter unfamiliar black males is not wholly irrational. (Roughly 50 percent of the violent crime in America is committed by young black males, who make up perhaps 3 percent of the population.) And needless to say, it isn't only whites who experience that fear. (Jesse Jackson confessed in 1993 that it pains him to have to walk down a dark street, hear footsteps, worry about being mugged -- " then look around and see someone white and feel relieved.")

But it is staggering that McCall, of all people, has the nerve to condemn such people. He is contemptuous of them? They make him bitter? This veteran gang-rapist and armed robber, this recovering hoodlum who beat, shot, mugged, terrorized, stole from, or forced himself on who-knows-how-many victims -- he has the effrontery to get angry when others grow nervous in the presence of black men they don't know? It is because of felons like him that such nervousness exists. He and his ilk are the reason that law-abiding black men so often encounter this humiliating distrust.

In a short essay titled "The Elevator Ride," McCall -- writing in the second person, presumably of himself -- scornfully describes a white woman who (he imagines) is filled with fear and "racial suspicion" as she descends with him in an elevator. "She suspects what you want," he seethes.

She seems filled with the wildly absurd terror that, in the brief ride between the 12th and 1st floors, this black man may rape her, rob her, and leave her for dead. . . . Can't she tell from your bearing that you're no rapist or thief?

Those italics, astonishingly, are the author's. "Can't she tell from your bearing that you're no rapist or thief?" Of course she can't tell that. How could she? She's in the elevator with Nathan McCall, writer, reporter, rapist, thief.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.