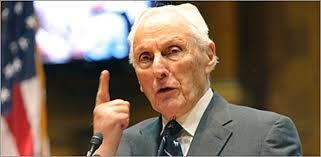

BRUCE SUNDLUN'S TERM as president of Temple Beth El, the largest Reform synagogue in Rhode Island, still had five months to run. But he didn't mind stepping down early, on January 1, to take up his new post: the state's 54th governor.

Sundlun, a Democrat, will now be the only Jewish chief executive of an American state. He also happens to be the only one of six Democrats who ran for governor in New England last November who was victorious. "I can hold meetings of the New England Democratic Governors' Conference in my bathroom," he observes. But if his victory was lonely, it was also impressive: a 74-26 landslide, the widest winning margin of any of the 36 governors' races nationwide.

It was, however, also very expensive. Sundlun, 70, a multi-millionaire, spent $ 4.1 million on his campaign, a staggering price to pay for one of the littlest prizes in gubernatorial politics. Rhode Island governors serve only two-year terms, and they preside over one of the union's smallest states, with only 995,000 residents.

Was it worth it? "From a business standpoint, it was stupid," he replies instantly. "But you get into a fight, and you do it right or you better not do it at all."

Sundlun is nothing if not a fighter. He served as a bomber pilot during World War II. When his B-17 "Flying Fortresses" was shot down by German fighters off the coast of Holland, he escaped capture, and made his way to Nazi-occupied Paris. There he joined the French resistance, and eventually returned, a decorated hero, to Rhode Island.

During Israel's War of Independence, Sundlun, who by then was a 28-year-old graduate of Harvard Law School, wanted to fly bombing runs against the Arabs. In the face of intense opposition from his father, however, he had to find a different way to help.

"I got three B-17s and crewed 'em over to Israel," he recalls. "In those days, there were hundreds of them parked in the desert in Arizona. Basically, we just took them. Whether that was legal or not, I've never been sure."

Since then, Sundlun has visited Israel many times. "The significance of the Jewish State to me personally is extreme," he says. "The State of Israel proved to the world that the Jewish characterization changed from the moneylender and the merchant to the soldier and the farmer. The world has always respected the soldier and the farmer."

Despite a privileged childhood, Sundlun was not spared the sting of the anti-Jewish bigotry that was endemic to prewar New England. He remembers the dancing school classmate who objected that "this place is going downhill -- they're starting to admit kikes." When he became a boy scout troop leader, one mother had her son transferred she didn't want him to be "contaminated" by Sundlun. He was barred from the Williams College football team in 1938, while the six German exchange students on the team waited for permission from home to play with him.

Still, despite his service as synagogue president, outward signs of Sundlun's Jewishness are limited. Only the first of his four wives was Jewish. He had virtually no Jewish education, could scarcely master the Hebrew for his bar mitzvah and does not put much stock in religion. Temple Beth El's rabbi, Leslie Gutterman, who acknowledges that Sundlun is not a Jew "whose piety is on display," brought the house down at a roast of Sundlun with the crack, "Bruce, you don't have to be ashamed you're Jewish. We are."

But Sundlun sums up his feelings about his faith in the following manner: "While nobody could ever claim that I am a very religious person, I know whence I come and take my Jewishness very seriously."