SOMETHING TO REFLECT on as you sit down to your Thanksgiving dinner: If you had been a Pilgrim, would you have given thanks?

Consider what they had been through, the men and women who broke bread together on that first Thanksgiving in 1621.

They had uprooted themselves and sailed for America, an endeavor so hazardous that published guides advised travelers to the New World, "First, make thy will." The crossing was very rough, and the Mayflower was blown off course. Instead of reaching Virginia, where Englishmen had settled 13 years earlier, the Pilgrims ended up in the wilds of Massachusetts. By the time they found a place to make their new home -- Plymouth, they called it -- winter had set in.

The storms were frightful. Shelter was rudimentary. There was little food. Within weeks, nearly all the settlers were sick. Many never recovered.

"That which was most sad and lamentable," Governor William Bradford later recalled, "was that in two or three months' time, half of their company died, especially in January and February, being the depth of winter, and wanting houses and other comforts; being infected with the scurvy and other diseases.... There died sometimes two or three of a day."

When spring came, they tried planting wheat, but the seeds they had brought from Europe wouldn't grow in the stony soil. Friendly Indians showed them how to plant corn, but their first crops were dismal. When supplies ran out, their sponsors in London refused to replenish them. And the first time the Pilgrims sent a shipment of goods to England, it was seized by pirates.

If you had been there in 1621 -- if you had seen half your friends and family die, if you had suffered through famine and sickness, if you had endured a year of disappointment and tragedy -- would you have felt grateful?

Gratitude isn't an emotion most of us cultivate. Even on Thanksgiving, we are more likely to concentrate on the turkey or the television than on giving thanks. But perhaps we would think differently about thankfulness if we realized its extraordinary power to improve our lives.

I mean something more than simply the civilizing benefits of good manners. Of course it is admirable to show gratitude. Nothing rankles more than showing kindness or generosity to someone who doesn't appreciate it.; that is why parents constantly coax their young children to say "please" and "thank you." But the value in giving thanks goes far beyond mere politeness. Gratitude is nothing less than the key to happiness.

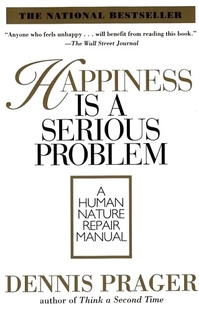

For this penetrating insight into gratefulness, I am grateful to Dennis Prager, author of Happiness is a Serious Problem.

"There is a 'secret to happiness,' " Prager writes, "and it is gratitude. All happy people are grateful, and ungrateful people cannot be happy. We tend to think that it is being unhappy that leads people to complain, but it is truer to say that it is complaining that leads to people becoming unhappy. Become grateful and you will become a much happier person."

It is a keen observation, and it helps explain why the Judeo-Christian tradition places such emphasis on thanking God. The liturgies are filled with expressions of gratitude. And rightly so, King David wrote in the 92nd Psalm: "It is good to give thanks to the Lord." Why? Because God needs our gratitude? No. Because we need it.

Learning to be thankful, whether to God or to other people, is the best vaccination against taking good fortune for granted. And the less you take for granted, the more pleasure and joy life will bring you.

If you never give a moment's thought to the fact that your health is good, that your children are well-fed, that you make a decent living, that your home is comfortable, that your nation is at peace, if you assume that the good things in your life are "normal" and to be expected, you diminish the happiness they can bring you. By contrast, if you train yourself to reflect on how much worse off you could be, if you develop the custom of counting your blessings and being grateful for them, you will fill your life with cheer.

It can be hard to do. Like most useful skills, it takes years of practice before it becomes second nature. This is one reason, Prager writes, that religion, sincerely practiced, leads to happiness -- it ingrains the habits of thankfulness. People who thank God before each meal, for example, inculate gratitude in themselves. In so doing, they open the door to gladness.

In a sense, gratitude is an expression of modesty. In Hebrew, the word for gratitude -- hoda'ah -- is the same as the word for confession. To offer thanks is to confess dependence, to acknowledge that others have the power to benefit you, to admit that your life is better because of their efforts. That frame of mind is indispensable to civilized society.

So be thankful. Don't take the gifts in your life for granted. Remember -- as the Pilgrims remembered -- that we are impoverished without each other, and without God. Whoever and wherever you are this Thanksgiving, the good in your life outweighs the bad. If that doesn't deserve your gratitude, what

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.