ONCE IN THE fourth grade I got caught in a lie. It wasn't an especially egregious lie; it endangered no one's safety or property. I had simply avoided a school activity by falsely claiming that I had my parents' permission not to take part. Somehow I was found out.

Here is how seriously my school took that small lie.

The assistant principal came to my classroom, interrupting the lesson that was in progress. He wrote a biblical quotation on the blackboard: "From false words keep thyself distant" (Exodus 23:7). He asked the class what the words meant, and made a point of calling on me for the answer. When he finished this impromptu exercise on the gravity of lying, he summoned me to his office. Only then did I find out that my deception had been exposed. He took a book from the office safe, turned to a clean page, and wrote down my lie. I had to sign the page and date it; the book went back into the safe.

Needless to say, I was mortified. But I learned some important lessons that day. I learned that my lies could disgrace me, that words are not easily erased, and that the adults in my life noticed when I did something wrong.

That's the kind of school I attended.

This is the kind of school Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the Colorado mass-murderers, attended:

They glorified Nazis, wore swastikas, and shouted "Heil Hitler!" when they were pleased. And no teacher, principal, or administrator, it seems, did anything about it.

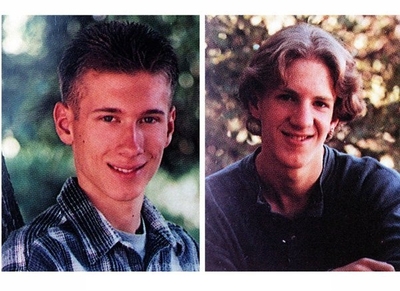

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, shown here in yearbook photos, killed 12 classmates and one teacher before killing themselves at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo. (Associated Press) |

They talked endlessly about explosives and guns, and filled a web page with details on how to make a bomb. "Shrapnel is very important," it said, "if you want to kill and injure a lot of people." For good measure, they illustrated the web site with drawings of a gunman firing at a bleeding and cowering victim. And no teacher, principal, or administrator, it seems, did anything about it.

For a class last fall, they made a video showing themselves walking down the hallways of Columbine High School, weapons in hand, shooting "jocks" dead. It was literally a rehearsal for a massacre – but no teacher, principal, or administrator, it seems, did anything about it.

The adults of Columbine High School were not alone in ignoring students' nastiness and brutality.

When Harris and Klebold were convicted of breaking into a van and trying to steal its contents, they were sentenced not to prison but to counseling. When a Columbine parent twice went to the sheriff last year to report that Harris had threatened his son – and supplied 15 pages of Harris's frightful Internet writings to substantiate his accusation – nobody acted. "You all better hide in your houses," Harris had written, "because I'm coming for everyone and I will shoot to kill and I will kill everything."

Last week Jefferson County Sheriff John Stone allowed as how he has "a real concern with people who identify with Adolf Hitler as a hero." It is easy to be concerned when 13 victims are dead and two dozen more have been wounded. It would have been more helpful if the sheriff had been concerned last year, when the evidence of Harris's repugnant character was first laid before him.

And where, pray, were the parents of Littleton when kids were showing up in school tricked out in ghoulish makeup? Or hanging out with an antisocial "trenchcoat mafia?" Or filling Web pages with bloody fantasies and idolizing "death rock" bands like KMFDM (sample lyric: "If I had a shotgun, I'd blow myself to hell")? Parents have always had their hands full with teen-agers. But in generations past, they managed to make even rebellious or spleeny adolescents understand that vicious behavior would trigger a crackdown. Holden Caulfield was alienated, but he never bombed his school.

The slaughter in Colorado has unloosed the usual gush of therapy-talk. The solution to student rampages is better mental health services, earlier detection of depression, more counselors, you name it. One expert told the New York Times that kindergarten teachers must be trained to screen for aggressive behavior. A 15-year-old Columbine girl said that Klebold "wasn't so bad" and she regretted not being able to "give him a hug and tell him that I care." Bill Clinton, the nation's therapist-in-chief, solemnly intoned that "we must do more to reach out to our children and teach them to express their anger and to resolve their conflicts with words, not weapons."

More of the same, in other words. More handholding. More narcissism. More nonjudgmentalism. More worship of self-esteem. More refusal to enforce standards of right and wrong. More of the flight from discipline and character.

"Teach them to express their anger?" "Give him a hug?" What the killers of Littleton needed was not more reassurance. Their problem wasn't a failure to express themselves. It was a failure to control themselves. And no wonder: Their lives were filled with adults who never set limits, never imposed rules, never made it clear that certain kinds of behavior would not be tolerated.

In parochial schools like the one I attended, children are taught that they may not say and do anything they please. They learn that their deeds have consequences, and that their demands are less important than their obligations. They are not indulged when they behave badly. They are not surrounded by grown-ups who shrug at Hitler salutes or web pages full of bloodthirsty fantasies. They are instructed from Day 1 in the difference between right and wrong, and in the values they are expected to uphold.

Maybe that is why none of these atrocities has happened in a parochial school – and why every public school in America has to fear that it may be next.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.