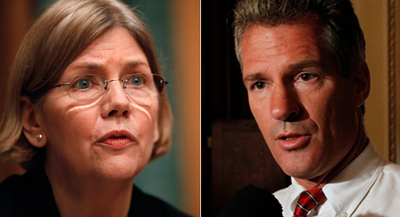

FOR SHEER ANTIDEMOCRATIC GALL, it is hard to top the so-called "People's Pledge" signed on Monday by US Senator Scott Brown and Harvard law professor Elizabeth Warren. The agreement is designed to keep third-party advertising from playing a role in their closely-watched race for the seat that Brown won in a special election in 2010. Of course there is not the slightest chance the deal will actually keep independent ads off the airwaves or the internet between now and November's election. Yet Brown and Warren claim to be sincere in their determination to keep third parties from trying to influence this year's campaign.

If so, shame on them.

The Republican incumbent and his presumed Democratic challenger have agreed that if an outside group spends money targeting either candidate in broadcast or online advertising, the campaign that benefits will suffer a financial penalty: It will have to donate half the value of that ad buy to a charity named by the other campaign.

Thus if the League of Conservation Voters were to sink another $1.85 million into commercials like the one that accused Brown of having "sided with Big Oil," the Warren campaign would have to fork over $925,000 to a charity designated by the commonwealth's Republican senator. And if Crossroads GPS chooses to double down on the $1.1 million it spent recently on anti-Warren videos, such as the one linking her to the bonuses bank executives were paid out of federal bailout funds, Brown's team would have to kiss $550,000 goodbye.

The candidates say their objective is to "provide the citizens of Massachusetts" with a Senate campaign free of messages coming from any source "outside the direct control of either of the candidates." On Monday, Brown proclaimed it a "great victory" that he and Warren have put "third parties on notice that their interference in this race will not be tolerated." But what they mean by "third parties" is not just heavily endowed superPACs parachuting in from out of state. They mean anyone not taking orders from them, including individuals, charitable groups, policy advocates, and party committees.

And what they mean by "interference" is political free speech.

Brown and Warren have a simple message for anyone with something to say about the Massachusetts Senate race: Shut up. To win one of the most powerful positions in American politics, they are prepared to spend tens of millions of dollars making sure that they are heard loud and clear by voters, donors, and opinion leaders. They won't hesitate to trumpet their views -- and make potentially momentous promises -- on issues ranging from taxes, health care, and the economy to foreign policy, immigration, and defense. They'll warn that America's future is riding on the outcome of their competition. Between now and Nov. 6, they'll be talking without letup about the urgency of this Senate race and the vital importance of electing the right candidate.

But if anyone else talks about it, that's "interference." Let voters, donors, and opinion leaders hear about Brown and Warren from someone other than the candidates themselves? That "will not be tolerated."

Far from deserving the props and applause they are collecting in some quarters, Brown and Warren deserve bipartisan scorn. There is nothing admirable about candidates for Congress seeking to squelch electoral speech. Brown and Warren wouldn't dream of demanding that news organizations refrain from commenting on the campaign or trying to influence voters. Why should any other organization -- liberal or conservative, broad-based or niche, brand-new or long-established, local or out-of-state -- be treated with any less deference?

"We have entered into this historic agreement," the Senate candidates' pledge says, "in order to ensure that in our race we each speak to the people of Massachusetts directly, as their candidates, and that our messages are not overtaken by special interests and outside agendas."

Were Brown and Warren really focused on limiting the influence of "special interests and outside agendas," they would be working to curtail the power and authority that Washington exerts over so much of American life. Even for a pair of Massachusetts politicians, it takes remarkable chutzpah to demand that citizens stifle themselves about a political choice that may affect their families and fortunes for years to come. If the candidates are overcome by an urge to silence political speech, let them tell each other to shut up. How dare they tell the rest of us to do so?

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter