ANY TIME IS THE RIGHT TIME to read Martin Luther King's 1963 "Letter from Birmingham Jail." But it pulses with special relevance during Black History Month.

We have fallen into the custom of treating this period as blacks' history month: four weeks set apart -- segregated, one might say -- for African-Americans to celebrate black heroes and recall black achievements. It has become a kind of calendrical quota -- 11 months of "regular" history, one month of black history. The result is a pervasive tokenism, with February becoming the month for black-themed lectures, concerts, and school assignments.

But as King would have been the first to insist, the history of blacks in America is not some detachable appendix to American history. It is American history. For all its dark and bloody episodes, it is the greatest success story of any black people, ever -- an ascent that can be comprehended only in the context of American values and traditions.

It was precisely those values and traditions to which King appealed in "Letter from Birmingham Jail."

"I am in Birmingham," he wrote, "because injustice is here."

So it was. Birmingham in 1963 was toxic with racism and segregationist to the core. Not long before, in the wake of the Montgomery bus boycott and the desegregation of Little Rock's schools, 17 of its black churches had been bombed. Indeed, there had been more unsolved bombings of black homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the United States.

For months, local black leaders had been trying to negotiate an easing of Birmingham's unrelenting segregation. Finally, in early April, King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference organized a nonviolent protest. "We had no alternative," King wrote, "except to present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the . . . community."

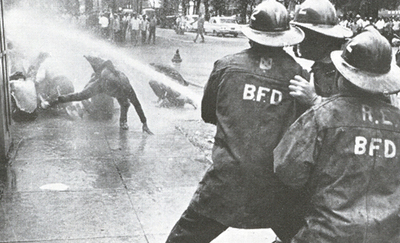

What ensued was horrific. Birmingham's public safety commissioner, Eugene "Bull" Connor, ordered police to stop the marchers. Unarmed men, women, and children were beaten with nightsticks and attacked by snarling dogs. As television cameras recorded the brutality, fire hoses were turned on the demonstrators. Hundreds were arrested, including King himself.

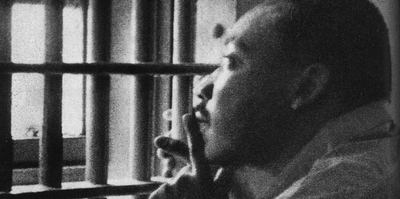

Earlier that year, eight white Alabama clergymen had published an open letter in the Birmingham Post Herald. They warned that the SCLC's crusade would only inflame unrest, and urged a halt to the demonstrations, calling them "unwise," "untimely," and "extreme." Now, locked in solitary confinement, King replied.

"For years now," he wrote, "I have heard the word 'Wait!' It rings in the ear of every Negro with a piercing familiarity. . . . We have waited -- for more than 340 years -- for our constitutional and God-given rights."

King's letter is one of the most lucid and persuasive American essays of the 20th century in part because it is an impassioned statement of faith in America's fundamental decency. King understood the power of conscience in American history. He knew that Americans would respond to the indignity of discrimination if only they could be made to see it. Racism might run deep, but a love of liberty and a passion for fairness ran deeper still. This was not some Communist dictatorship or African police state, where dissidents simply vanished in the night. Here a dissident could speak and be heard -- even from a jail cell in Alabama.

To be black in 1963, King wrote in one heartrending passage, is to "suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your 6-year-old daughter why she can't go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her little eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see the depressing clouds of inferiority begin to form in her little mental sky." It is to be "humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading 'white' and 'colored.' " It is "when your first name becomes 'nigger' and your middle name becomes 'boy.'. . . There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over. "

Only in form was King's letter addressed to the eight clergymen. In reality he was appealing to the tens of millions of white Americans he knew would rally to the cause of civil rights -- once they understood what was at stake.

On the orders of Bull Connor, high-pressure fire hoses were used against nonviolent civil-rights marchers. |

"I have no fear about the outcome of our struggle in Birmingham," King wrote. "We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom. Abused and scorned though we may be, our destiny is tied up with the destiny of America. Before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, we were here. Before the pen of Jefferson etched the majestic words of the Declaration of Independence, we were here. . . . We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands."

We know how the story ends. King was released. Birmingham was desegregated. The Civil Rights Act became law. King won the Nobel Prize. It is a shining chapter in history. Not black history, American history. Our history.

"When these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters," wrote King on the last page of his letter, "they were in reality standing up for the best in the American dream and the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage, thus carrying our whole nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the Founding Fathers."

From those wells all of us draw, all 12 months of the year.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.