NEWT GINGRICH'S PRESIDENTIAL AMBITIONS may be heading for the exits -- opinion polls suggest that the former House speaker's hour has come and gone -- but his critique of judicial supremacy deserves to be taken seriously no matter what happens in Iowa or New Hampshire.

Contrary to popular belief, their judgments were never meant to be revered "almost as if God has spoken." |

In a 54-page position paper, Gingrich challenges the widely held belief that the Supreme Court is the final authority on the meaning of the Constitution. Though nothing in the Constitution says so, there is now an entrenched presumption that once the court has decided a constitutional question, no power on earth short of a constitutional amendment -- or a later reversal by the court itself -- can alter that decision.

Thus, when House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi was asked for her reaction to the Supreme Court's notorious eminent-domain ruling in Kelo v. New London, she replied as though a new tablet had been handed down from Sinai: "It is a decision of the Supreme Court. If Congress wants to change it, it will require legislation of a level of a constitutional amendment. So this is almost as if God has spoken."

But judges are not divine and their opinions are not holy writ. As every American schoolchild learns, the judiciary is intended to be a co-equal branch of government, not a paramount one. If the Supreme Court wrongly decides a constitutional case, nothing obliges Congress or the president -- or the states or the people, for that matter -- to simply bow and accept it.

Naturally this isn't something the courts have been eager to concede. Judges are no more immune to the lure of power than anybody else, and their assertion of judicial supremacy -- plus what Gingrich calls "the passive acquiescence of the executive and legislative branches" -- has won them an extraordinary degree of clout and authority. That aggrandizement, in turn, they have attempted to cast as historically unassailable. In Cooper v. Aaron, the 1958 Little Rock desegregation case, all nine justices famously declared "that the federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constitution" -- a principle, they asserted, that has "been respected by this court and the country as a permanent and indispensable feature of our constitutional system."

That wasn't really true. In the words of Larry Kramer, dean of Stanford's Law School (and a former clerk for Justice William Brennan, one of the court's liberal lions), "The justices in Cooper were not reporting a fact so much as trying to manufacture one." It worked. In recent decades, the claim of judicial supremacy has clearly prevailed. Look at the way it's taken for granted, for example, that whatever the Supreme Court decides next spring about the constitutionality of the ObamaCare insurance mandate will settle the issue once and for all.

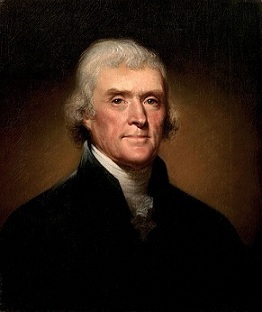

"To consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions," wrote Thomas Jefferson in 1820, is "a very dangerous doctrine indeed." |

Gingrich argues that this is unhealthy, and that the elected branches have an obligation to check and balance the judiciary. "The courts have become grotesquely dictatorial, far too powerful and, I think, frankly arrogant," he said in Iowa last month. From the unhinged reaction his words provoked -- "this attempt to turn the courts into his personal lightning rod of crazy is simply Gingrich proving yet again that he needs to be boss of everything," railed Dahlia Lithwick in Slate -- you'd think he had declared war on the heart and soul of American democracy.

But the heart and soul of American democracy is that power derives from the consent of the governed, and that no branch of government -- executive, legislative, or judicial -- rules by unchallenged fiat. Gingrich is far from the first to say so.

"To consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions," wrote Thomas Jefferson in 1820, is "a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy." Abraham Lincoln -- revolted by the Supreme Court's ruling in Dred Scott that blacks "had no rights a white man was bound to respect" -- rejected the claim that the justices' word was final. "If the policy of the government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court the instant they are made," he warned in his first inaugural address, "the people will have ceased to be their own rulers."

Not all of Gingrich's proposals for reining in the courts, such as summoning judges before congressional committees to explain their rulings, may be wise or useful. But his larger point is legitimate and important. Judicial supremacy is eroding America's democratic values. For the sake of our system of self-government, the balance of federal power needs to be restored.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --