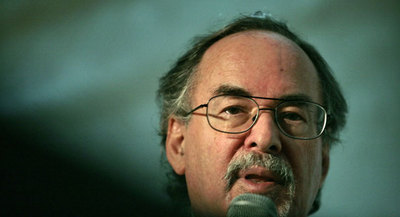

DAVID HOROWITZ aches to believe that life has meaning and that there is a purpose to this world. The prolific writer, a former Marxist radical who became a leading conservative activist, has spent his (so far) 72 years as if how we live matters deeply. Still, he cannot shake the bleak intellectual conviction that in the long run nothing we do will endure or make a difference — that life on earth is ultimately meaningless and history is heading nowhere.

Yet Horowitz's own journey suggests something more hopeful and optimistic.

He was a militant leftist who opposed the Vietnam War and supported the Black Panther Party, but broke with his radical allies over the bloody repression that followed the communist victories in South Vietnam and Cambodia. By the 1990s he had become one of the most vocal opponents of political correctness in academia, and he emerged after 9/11 as an outspoken critic of radical Islam.

In his brief and affecting new book, A Point in Time, Horowitz wrestles with even deeper concerns. He writes admiringly of Marcus Aurelius, the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher whose "practical wisdom" was that life's torments -- and tormentors -- should be faced with equanimity, since oblivion is the common fate of all. "Be not troubled," advised the emperor, "for all things are according to nature, and in a little while you will be no one and nowhere." It is a passage Horowitz quotes several times. He is at peace with the prospect of dying, he says, "comfortable with the idea that soon I will be no one and nowhere, and comforted in a stoic way by the knowledge that it doesn't add up."

Is he, though? As Horowitz notes, even Marcus Aurelius was "haunted" by the implications of a world without transcendent meaning. If the universe is nothing but "a confused mass of dispersing elements," the great Stoic wrote -- if there is no God, no perfection, no possibility of redemption -- why do we hunger to live? Why do we have such hopes for the future?

In the end Marcus Aurelius decides that "there are certainly gods, and they take care of the world." But that is a step too far for Horowitz. Though Jewish, he is an agnostic, unable to bring himself to belief in God or in an afterlife where justice finally prevails. "I wish I could place my trust in the hands of a Creator," he writes forlornly at one point. "I wish I could look on my life and the lives of my children and all I have loved and see them as preludes to a better world. But, try as I might, I cannot."

As it happens, I read A Point in Time during the High Holidays, the 10 days of repentance that extend from Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, through Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. One of the great themes of this solemn interval is that life on earth is fleeting, and so we must make the most of it. In the evocative words of "U'Netaneh Tokef," an emotional high point of the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur liturgy, man is "like a broken shard, like grass dried up, like a faded flower . . . like a dream that slips away."

Contrary to the Stoics, however, Judaism regards human mortality not as a reflection of the world's meaninglessness, but as God's greatest gift to the men and women He creates in His image. A lifetime — that brief window between dust and dust — is the opportunity He grants each of us to become His partners in creation by making the world a better, kinder, more hopeful place. Our job is not to accept the world as it is, nor to make our peace with the idea that eventually we "will be no one and nowhere." Judaism believes in life after death, but it is only in life before death that human achievement is possible.

And there is no achievement greater than self-improvement.

Judaism is the religion of the free human being freely responding to the God of freedom. |

"If the world is to be redeemed it will be one individual at a time," Horowitz writes at the end of his book. The religion of his fathers teaches not just that individuals have the power to improve themselves ethically, but that their ability to do so is a divine endowment.

"Judaism is the religion of the free human being freely responding to the God of freedom," observes Sir Jonathan Sacks, the British chief rabbi, in his introduction to a new edition of the Rosh Hashana prayerbook. "The very fact that we can . . . act differently tomorrow than we did yesterday tells us we are free. We are not in the grip of sin. We are not determined by economic forces or psychological drives or genetically encoded impulses that we are powerless to resist. Philosophers have found this idea difficult. So have scientists. But Judaism insists on it."

David Horowitz may not believe in the Creator from whom this freedom comes. But his life -- and A Point in Time -- attest eloquently to the meaning and moral progress that are possible when that freedom is cherished, and used wisely.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.