President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act on August 14, 1935.

Second of two parts (Read Part 1)

MY MOTHER'S MOTHER revered Franklin Roosevelt. She voted for him four times, and firmly defended him decades later, when I tried to convince her that FDR was not the haloed saint she imagined.

"It's because of Roosevelt that I'm getting $800 in Social Security every month," she'd tell me. Actually, I'd reply, it was because of people like me -- younger workers paying into the system, at tax rates considerably steeper than hers had ever been -- that retirees like her were receiving those monthly checks.

But like millions of seniors then and now, Grandma was convinced that her Social Security benefits were an entitlement she had bought with her own payroll taxes years earlier. She blessed FDR for creating the Social Security trust fund in which she had faithfully invested for most of her working life, and couldn't understand why her grandson had any objection to it.

In reality there is no money in Social Security's trust fund and never has been. It is merely an accounting fiction, like the individual Social Security accounts to which workers' payroll taxes are credited. But Grandma could hardly be blamed for believing otherwise. Right from the start, Social Security was promoted to Americans as a straightforward pension fund. "We have set up a savings account for the old age of the worker," FDR told a Pennsylvania audience in 1936. Contributions would be made by employers and employees via payroll taxes, which would be "held by the government solely for the benefit of the worker in his old age."

It wasn't true. In a decision the following year upholding the Social Security Act, the Supreme Court confirmed what anyone who read the law would already have discovered: Payroll taxes weren't held by the government solely for the benefit for retirees. On the contrary: Social Security taxes "are to be paid into the Treasury like internal revenue taxes generally, and are not earmarked in any way."

Likewise, for all the talk of Social Security as an "entitlement," retirees have no ironclad right to that monthly check. "Congress can change the rules" whenever it wants to, the Social Security Administration's website acknowledges. "Benefits which are granted at one time can be withdrawn." That too was explicit in the law FDR signed in 1935. There are no "accrued property rights" in the Social Security system, the Supreme Court ruled in 1960. Payroll taxes withheld from your wages today don't confer on you a contractual right to benefits when you retire tomorrow.

Yet is it any wonder so many Americans believe the opposite? They have been assured for years that Social Security's considerable surpluses have been piling up in a trust fund worth about $2.6 trillion at last report. With assets like that, insist the status quo's defenders, there will be enough money to pay retirees' benefits for decades to come.

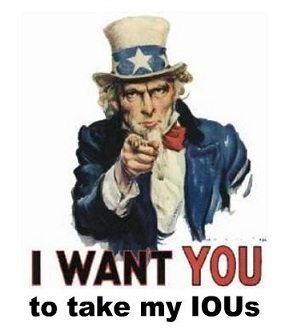

But the trust fund's assets are an illusion. Social Security doesn't own $2.6 trillion in gold bars or real estate or shares of Google. All it has are Treasury IOUs. Those IOUs represent $2.6 trillion that the government has already spent and promises to spend again. But in order to spend it again -- to redeem those IOUs -- Congress will have to raise taxes, cut spending, or go deeper into debt. Which is exactly what Congress would have to do if the Social Security trust fund didn't exist.

A US government bond is a sound and valuable asset -- for anyone but the US government. Just as you don't increase your wealth when you write yourself a check, the government cannot sock away $2.6 trillion by promising to pay itself $2.6 trillion. "The assets of the Social Security trust fund," the Congressional Budget Office has explained, "do not represent any real stock of resources set aside to pay for benefits in the future." The trust fund is a ledger entry, nothing more.

President Obama suggested in July that without a debt-ceiling increase, Social Security checks might not go out "because there may simply not be the money in the coffers to do it." Granted, he was playing political hardball. But he was also conceding the inescapable truth about Social Security's vaunted trust fund: It doesn't exist.

With the baby-boom generation beginning to retire, Social Security is projected to lose money every year from now on, beginning with a $45 billion shortfall this year. There is no trust-fund hoard to cover those losses. FDR's signature program is on a collision course with itself. My grandmother, may she rest in peace, may have believed it would last forever. My generation doesn't have that luxury.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.