THE DECLARATION of Independence announced to the world the birth of a new nation, said President Calvin Coolidge on the Declaration's 150th anniversary, and every birth "excites our interest." But that is not why July 4, 1776, "has come to be regarded as one of the greatest days in history."

Since ancient times there had been many revolutions, after all; new nations had broken away from old empires before. What makes America's founding extraordinary, observed the 30th president -- the last, incidentally, who wrote his own speeches -- is that it was the first to be based not on blood or soil but on a set of philosophical ideas about "the nature of mankind and therefore of government." Other nations have their deepest roots in ethnicity, tribal loyalty, or military conquest. America, uniquely, was dedicated to a proposition -- to the fundamental, self-evident truth "that all men are created equal" and the political ideas that flow from that truth.

The doctrine that human beings are by nature equal is one that Americans of the Founders' era had learned from both philosophy and religion.

In 1690, in his influential Second Treatise of Government, the English philosopher John Locke had written that the "state all men are naturally in" is one of "perfect freedom to order their actions and dispose of their possessions ... as they see fit," as well as one "of equality, wherein all the power and jurisdiction is reciprocal ... without subordination or subjection." Even older, and no less influential, was the biblical teaching that because all human beings are made in the image of God, all are born with the same God-given right to equality and freedom.

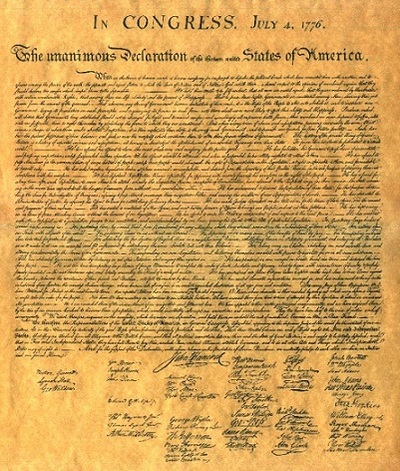

So when delegates to the Continental Congress declared unanimously in 1776 "that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness," their words accurately reflected what Americans had believed for generations. They invoked "the laws of Nature and of Nature's God" in the Declaration's opening line not as a throat-clearing flourish, but because those laws and that God validated the independence they were about to assert. "Coming from these sources, having as it did this background," remarked Coolidge, "it is no wonder that Samuel Adams could say, 'The people seem to recognize this resolution as though it were a decree promulgated from heaven.'"

If Nature and Nature's God intended human beings to be free and equal, then the only legitimate government must be self-government. For if none of us is naturally subordinate or superior to anyone else, no one has the right to rule us without first obtaining our approval. Political power, Locke had written, stems "only from compact and agreement, and the mutual consent of those who make up the community."

The Declaration of Independence emphasized the point. Not only are all persons endowed by nature with the unalienable rights of equality and freedom, it avowed, but "to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed."

No lawful government without consent and self-rule: It was an extraordinary doctrine for its time. It had never been the springboard from which a new nation was launched. Yet to pursue this "theory of democracy," as Coolidge called it, "whole congregations with their pastors" had pulled up stakes in Europe and migrated to America.

Steeped in the imagery of the Hebrew Bible, the colonists believed that God had led them, as He had led ancient Israel, from a land of bondage to a blessed Promised Land. Thomas Jefferson suggested in 1776 that the seal of the United States should depict the "Children of Israel in the Wilderness, led by a Cloud by Day, and a Pillar of Fire by night." In that wilderness, Americans knew, God did not simply impose his rule on Israel. First the Hebrews had to give their consent: "And all the people answered together, and said, All that the Lord has spoken we will do." Only then was there the revelation at Sinai, the Ten Commandments, and the Law. If God Himself would not govern without the consent of the governed, surely King George had no right to do so!

July 4th marks more than American independence. It commemorates the great political ideals, rooted in faith and philosophy, that vindicated that independence -- and thereby transformed the world.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter