LARGER FAMILIES need larger houses. A larger nation does, too.

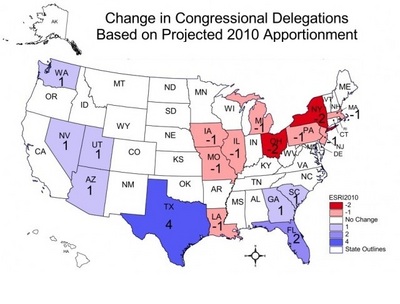

With the release of the 2010 Census data, the decennial rejiggering of the nation's political map has begun. Eight states will be gaining seats in the US House of Representatives, while 10 states' House delegations will shrink. (Those states will also gain or lose an equal number of votes in the Electoral College.) Among the winners are Texas, where the number of residents has soared by 4.3 million since the 2000 Census; Utah, whose population is up by more than 530,000; and Washington, which has grown 14 percent, to 6.7 million.

It stands to reason that states with more people are allotted more House seats. That is exactly what the Framers intended, as James Madison made clear in Federalist No. 55. "I take for granted," he wrote, "that the number of representatives will be augmented from time to time in the manner provided by the Constitution."

It would likewise stand to reason if the states losing House seats -- New York, Ohio, Massachusetts, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Missouri, Michigan, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania -- had all lost residents since 2000. But except for Michigan, all of the reapportionment losers gained population over the past decade. Massachusetts grew by nearly 200,000, yet it is losing a seat in Congress. There are more than 400,000 additional New Yorkers, but the number of House members representing them will drop by two.

For most of American history, the size of the House was adjusted upward every 10 years. The initial 65-member House prescribed in the Constitution was expanded to 105 members after the 1790 Census, to 142 members after the 1800 Census, and so on right through the 19th century. Following the 13th census, in 1910, Congress enlarged the House to 435 members -- and there it has remained, even as the American nation has more than tripled, from 92 million to 308 million. Ever since, the apportionment process has been able to allot new House seats to the fastest-growing states only by subtracting seats from states growing more slowly. One result is that many states have more voters, but fewer US representatives.

Another result, equally troubling, is that voters in some states have considerably more electoral clout than voters in others.

According to the Census Bureau, there are now 710,767 Americans in the average congressional district. But with every state constitutionally entitled to at least one House seat, and with the membership of the House frozen at 435, districts can deviate widely from the average. Wyoming's single US representative has just 568,000 constituents; the member from neighboring South Dakota has 820,000. That means a vote cast in Wyoming has nearly 1.5 times the impact of a South Dakotan's vote.

An even more egregious violation of the "one man, one vote" principle is the inequality between Rhode Island's two congressional districts, with 528,000 voters each, and Montana's lone district, with a population of 994,000. So great is that disparity, notes Scott Scharpen, the founder of the group Apportionment.US, that it takes 188 voters in Montana to equal 100 voters in Rhode Island.

The US Supreme Court earlier this month refused to take up a lawsuit, initiated by Scharpen and others, that sought an order forcing Congress to dramatically enlarge the House of Representatives in order to equalize congressional districts. Unsurprisingly, the court ruled that the size of Congress is for members of Congress, not judges, to decide.

But few members of Congress will voluntarily dilute their own power by voting to expand the House; only significant grassroots pressure (or a constitutional amendment) will ever force them to act. Until they do, the inequities caused by having a "people's house" fixed at 435 members will only grow worse.

The larger districts grow, the less representative lawmakers become. Since 1910, the number of constituents per House member has climbed from 210,000 to more than 710,000. Over the same span, members of Congress have grown more remote, more undefeatable, more beholden to special interests, and less capable of reflecting the diversity of their districts' values and views. Smaller, more numerous districts would be far more democratic, more accessible to new blood and new ideas, and more difficult to gerrymander.

Congress worked better when the size of the House was elastic. The Framers thought congressional districts should contain about 30,000 constituents; districts comprising nearly three-quarters of a million would have struck them as ludicrous. A 435-member House was fine for 1910. It's time we traded up to something bigger.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.)

-- ## --