Massachusetts and Rhode Island were two of the 16 finalists named this week in the Obama administration's "Race to the Top" competition for a share of $4.3 billion in education "stimulus" funds. Education Secretary Arne Duncan announced the finalists on Thursday; those that made the cut have agreed to embrace policies favored by the administration, such as higher caps on charter schools and tying teachers' raises to performance.

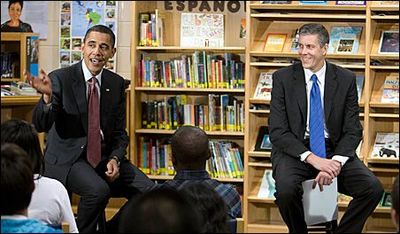

President Obama and U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan visiting Wright Middle School in Madison, Wis., last fall. |

The argument for national standards seems straightforward. The No Child Left Behind law enacted in 2002 required the states to establish their own academic standards, but most of them -- under pressure from teachers' unions and school administrators' associations -- set the bar quite low. In a 2006 report, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation concluded that most states' standards were "mediocre-to-bad . . . They are generally vague, politicized, and awash in wrongheaded fads and nostrums. With a few exceptions, states have been incapable (or unwilling) to set clear, coherent standards." The only way around the states' aversion to high standards, the Obama administration and others have concluded, is to impose uniform national standards, using the federal purse as leverage.

But if the goal is to have more American students get a successful education, it is far from clear that imposing a single set of benchmarks from above is the best strategy for getting there.

For one thing, the political resistance to rigorous academic standards that has been so effective at the state level is likely to be effective at the national level. The teachers' unions and administrators' organizations that oppose higher performance mandates are at least as influential on Capitol Hill as they are in the statehouses. The Cato Institute's Neal McCluskey points out that the National Education Association, the American Federation of Teachers, the American Association of School Administrators, the National Association of Elementary School Principals, and the Council of Chief State School Officers all make their national headquarters in Washington, DC. Whether in the states or in Washington, McCluskey writes, "the political system is stacked against high standards and tough accountability."

Moreover, the very nature of American society -- a nation of 300 million that comprises a multitude of ethnic, religious, social, and ideological traditions -- argues against the imposition from above of one-size-fits-all education standards. There is no uniform answer to the question of what parents want most from their children's education. "The greater the diversity of the people falling under a single schooling authority," McCluskey observes, "the greater the conflict, the less coherent the curriculum, and the worse the outcomes."

Anyone who called for legislation to establish mandatory national standards for television programming or restaurant menus would be laughed at: No one thinks the government is competent to decide what shows they can watch on TV or what they can order for dinner when they eat out. Is it any less risible to think that government knows best when it comes to your children's education?

Rather than centralizing even more government authority over education, genuine reform would move in the opposite direction. It is parents -- not local, state, or federal officials -- who should control education dollars. School and state should be separated, with schools being funded on the basis of their ability to attract students and teach them well. The primary responsibility for children's education should be vested in the same people who bear the primary responsibility for their feeding, housing, and religious instruction: their mothers and fathers.

More government control is not the cure for what ails American schools. The empowerment of parents is. No teachers' union, no school board, no secretary of education, and no president will ever love your children, or care about their schooling, as much as you do. In education as in so much else, high standards are important -- far too important to hand off to the government.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.)

-- ## --