DENOUNCING the Supreme Court's Jan. 21 ruling in the Citizens United campaign-finance case, President Obama called it "a green light to a new stampede of special interest money in our politics" and "a major victory for big oil, Wall Street banks, health insurance companies, and the other powerful interests." He denounced it again in his State of the Union address last week, saying it would "open the floodgates for special interests" and adding: "I don't think American elections should be bankrolled by America's most powerful interests."

The Senate's top recipient of special-interest contributions is outraged by the Supreme Court's ruling. |

Obama isn't the only critic of the high court's decision whose outrage at the thought of corporate influence in political campaigns seems a trifle ... contrived. Senator Charles Schumer, a New York Democrat, condemned the court for having "predetermined the winners of next November's elections. It won't be Republicans. It won't be Democrats. It will be corporate America." Coming from Schumer, that's a curious complaint: He is the Senate's leading recipient of campaign contributions from political action committees and other donors in nearly two dozen industries, including real estate, construction, securities, liquor, insurance, and hedge funds.

Worse than hypocrisy, though, is the condescension for voters that underlies so much of the fury aimed at the Supreme Court's ruling.

Newsweek's Jonathan Alter wailed in alarm that "if Goldman Sachs wants to pay the entire cost of every congressional campaign in the US, the law of the land now allows it." (Actually, it doesn't: The decision left intact the ban on direct corporate donations to politicians.) Alan Colmes, the house liberal at Fox News, predicted a "corporate takeover over of America." Monica Youn of the Brennan Center for Justice, writing before the ruling was handed down, warned that if the justices deregulated corporate political speech "voters will be forced into a couch-potato role, mere viewers of the electoral spectacle bought and paid for by wealthy companies."

But voters are not mindless dolts. Campaign advertising doesn't turn them into automatons, blindly voting for whichever candidates "approve this message" the most. American politics is replete with candidates and campaigns that lost handily, notwithstanding the fortune spent on newspaper ads, radio spots, and TV commercials promoting them. The court's decision simply allows corporations, like countless other associations and groups, to have their say during election campaigns. It has no effect at all on the ability of voters to ignore what those corporations may choose to tell them.

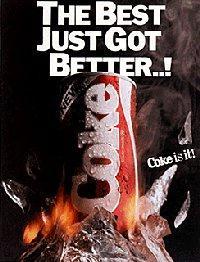

New Coke: Corporate advertising is hardly irresistible. |

Whether corporations will walk through the door the Supreme Court has now opened for them is not clear. Many corporations will doubtless avoid taking sides in heated election campaigns for fear of antagonizing their customers; others may decide that government-relations budgets are better spent on quiet lobbying than on open electioneering.

But even those that do choose to advertise during an election cycle will not make the mistake so many of the court's detractors are making. They know that Americans are not sheep, easily herded by means of clever commercials. If corporate advertising was irresistible, after all, we'd all be drinking New Coke.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --