1. According to the Constitution, how many members serve in the House of Representatives?

2. Why did the Framers believe the size of the House should be kept at a fixed number?

3. As of 2009, which of the following approximates the number of residents in each congressional district: (a) 530,000 (b) 700,000 or (c) 970,000?

Go to the head of the class if you recognized all three as trick questions.

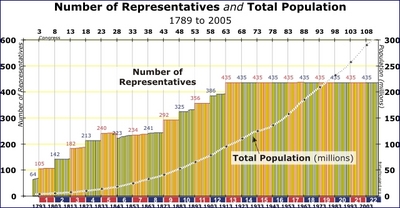

To begin with (answering Question 1), the Constitution does not stipulate the number of House members, other than allowing no more than one representative for every 30,000 residents. Sixty-five men were elected to the first House of Representatives, but it was taken for granted that the membership would increase with the nation's population.

Far from favoring a fixed membership for the House (Question 2), the Framers opposed the idea. They went out of their way to dispel "fears arising from the smallness of the body," as James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 55, and took it "for granted . . . that the number of representatives will be augmented from time to time in the manner provided by the Constitution." Madison reinforced the point in Federalist No. 56, assuring those who worried that a 65-member House would grow distant and oligarchical that "the foresight of the [Constitutional] Convention has . . . taken care that the progress of population may be accompanied with a proper increase of the representative branch of the government."

Since 1911, the number of House seats has been frozen at 435. The number of Americans, meanwhile, has tripled. |

Nearly a century later, the House membership remains frozen at 435, even as the US population has surged to 305 million. There are now more than 700,000 Americans for each member of the US House, which is another way of saying that the average congressional district is home to 700,000 constituents.

Yet 700,000 is not the correct answer to Question 3. Since every state is entitled to at least one House seat, and since the population of every state cannot be divided evenly into multiples of 700,000, the number of residents in each congressional district varies sharply. At the extremes, Montana's lone US representative has 967,000 constituents, while the member from Wyoming represents fewer than 533,000. That disparity -- more than 430,000 between the largest congressional district and the smallest -- means that residents of some states have considerably more voting power in Congress than residents of others. And that, insist the plaintiffs in a lawsuit making its way through a federal court in Mississippi, violates the principle of one-person, one-vote.

The lawsuit argues that only by enlarging its membership to at least 932 -- or better yet, 1,761 -- can the House return to districts of equal size. Whether the suit will succeed is an open question. But what a blessing if it did! Quadruple the size of the House, and congressional districts would again be small and compact, ideally suited to the retail politics of an earlier era, and more closely aligned with discrete communities and neighborhoods. Enlarge the House, and it would fill with new blood, new thinking, and new energy. Elections would be more competitive, since it would take fewer votes to win. The House would grow more diverse, more lively, more representative.

Today's incumbents would hate the idea, of course: It would dilute their power and make them more accountable. For a congressional baron, there could be no fate more odious. But James Madison would certainly approve.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.)

-- ## --