Second of three columns (Read Part 1)

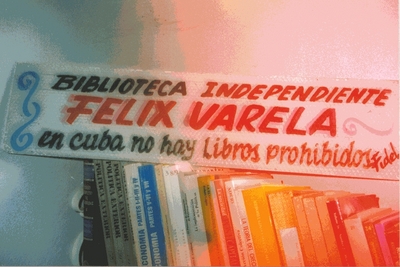

HAVANA -- "There are no banned books in Cuba," Fidel Castro declared in February 1998, "only those which we have no money to buy."

Of course, books are banned in Cuba; just try to locate one that criticizes Castro. Bookstores and public libraries here carry works exalting Marxism, but you won't find The Gulag Archipelago or Darkness at Noon on their shelves.

So when Ramon Humberto Colas, a psychologist in Las Tunas, heard Castro's words, he and his wife Berta Mexidor decided to put them to the test. They designated the 800 or so books in their home as a library and invited friends and neighbors to borrow them for free. And so was born the first of Cuba's independent libraries -- independent of state control, of censorship, and of any ideology save the conviction that it is no crime to read a book.

". . . No Books Prohibited" -- A sign in the Félix Varela Independent Library, Las Tunas, Cuba |

The men and women who run these humble libraries risk government retaliation; several have been threatened, interrogated, raided by the police -- or worse. Colas and Mexidor were evicted from their home, denounced in the (state-owned) press, and repeatedly arrested. Their books were confiscated. They were fired from their jobs. Their daughter was expelled from school. Government persecution eventually drove them from Cuba, but the seed they planted bore fruit. Today there are more than 100 independent libraries in homes across the country, each one a little island of intellectual freedom.

In Gisela Delgado's library in Havana, visitors can borrow Spanish translations of Adam Michnik's "Letters from Prison," Vaclav Havel's "The Power of the Powerless," or the speeches of Martin Luther King. On her shelves are everything from art to philosophy, but when I ask which books are the most popular, she doesn't hesitate: "Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-four." It does not come as a surprise that readers in this hemisphere's only totalitarian outpost hunger for the greatest antitotalitarian novels ever written.

The Castro regime boasts, justifiably, of having wiped out illiteracy. That makes it all the more unforgivable that it has turned the lending of books into an act of defiance. Dissent in Cuba takes many forms, but there is none that shames the regime more than this one.

Like most communist countries, Cuba is plagued with shortages of everything from food to electricity, but political dissidents it has in abundance. The government maligns them as malcontents and traitors -- "all these people are financed by the United States," sneers Fernando Remirez, Cuba's deputy foreign minister -- but the dissidents I met here uniformly come across as men and women of integrity and courage.

On my first day in Havana, I visited Oscar Espinosa Chepe, an economist who lost his job at the National Bank of Cuba -- and whose wife was fired from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs -- when he began calling publicly for economic reform. Bluff and good-natured, he describes himself as a former true believer who gradually came to realize the truth about Castro.

"He turned out to be someone who did everything for his own power," Espinosa says. "Life in Cuba is a mixture of Stalinism and caudillismo" -- rule by a caudillo, a Latin dictator -- "and there are no parties, no opposition, no elections, no choices."

Another one-time true believer, Martha Beatriz Roque, was a professor of statistics at the University of Havana who fell out of favor for praising glasnost and perestroika. In 1997, she and three other dissidents released a report criticizing Cuba's communist economy and urging a peaceful transition to democracy. For that offense, they were arrested on charges of spreading "enemy propaganda," and convicted in a one-day show trial that was closed to the public. Roque and two of the others spent nearly three years in prison; the fourth, Vladimiro Roca, is still there.

Roque has been detained by the police 17 times; her home has been broken into and searched; she assumes her phone is tapped and her visitors spied on. But she doesn't fear for her safety. Well-known dissidents like her and Espinosa and the others I met -- Elizardo Sanchez, Oswaldo Paya, Ricardo Gonzalez -- are protected by their international reputations. If something happens to them, says Roque, "people outside Cuba will make a big noise."

What worries her more is the fate of dissidents who aren't as well known. Juan Carlos Gonzalez, for example -- the blind president of the Cuban Foundation for Human Rights, who was abducted by the security police and battered so badly he needed stitches in his head. Or 70-year-old Juan Basulto Morell, a dissident journalist who was beaten bloody with a club as his assailant yelled, "This is for being a counter-revolutionary."

In Cuba, as in all dictatorships, it is the dissenters who sustain hope and keep conscience alive. On this tormented island, they are the bravest and the best.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.