OF THE 2.3 million people incarcerated in prisons and jails in the United States, roughly 140,000, or 6 percent, are serving life sentences. Of that number, about 41,000 -- i.e., 29 percent of the lifers, or 1.8 percent of all inmates -- were sentenced to life without parole. Both numbers are at an all-time high.

Should Americans be troubled by this? The Sentencing Project thinks so. In a new report, the liberal advocacy group -- which describes itself as a promoter of "alternatives to incarceration" -- complains that the growth in life sentences has been costly and unjust. It "challenges the supposition that all life sentences are necessary to keep the public safe." It particularly disapproves of life-without-parole sentences, which, it claims "often represent a misuse of limited correctional resources and discount the capacity for personal growth and rehabilitation that comes with the passage of time."

As a matter of policy, the Sentencing Project supports abolition of both the death penalty and life without parole. In its view, even a vicious mass murderer deserves a chance at parole. That is an eccentric position that most Americans clearly don't share. Nevertheless, the group's new report -- "No Exit: The Expanding Use of Life Sentences in America" -- has drawn media attention; stories have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, USA Today, and Agence France-Presse, among other outlets.

But good PR is not a substitute for sound analysis.

The problems with "No Exit" begin with the first paragraph, which asserts that the high incarceration rate in the United States is the result of "three decades of 'tough on crime' policies that have made little impact on crime."

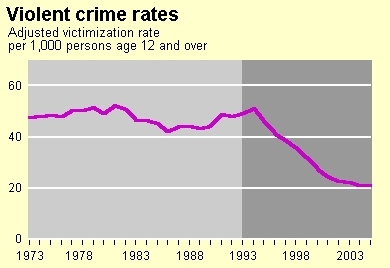

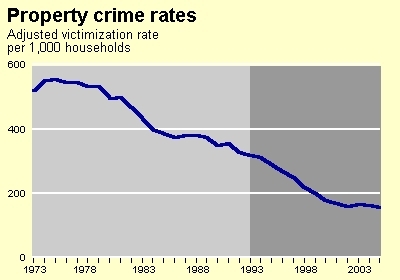

America's prison population has indisputably grown in recent years, as prison sentences have lengthened and more criminals have been locked up. But far from negligible, the "impact on crime" has been dramatic. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Americans experienced 44 million crimes in 1973. By 2007, the number of criminal victimizations had dropped to 23 million. During those "three decades of 'tough on crime' policies," in other words, crime in America was nearly halved -- and this even as the population grew by more than 75 million. Since the mid-1990s, the plunge in violent crime has been especially steep: from more than 51 crimes of violence per 1,000 US residents in 1994 to 21 in 2005 -- a 59 percent reduction.

America's prison population has indisputably grown in recent years, as prison sentences have lengthened and more criminals have been locked up. But far from negligible, the "impact on crime" has been dramatic. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Americans experienced 44 million crimes in 1973. By 2007, the number of criminal victimizations had dropped to 23 million. During those "three decades of 'tough on crime' policies," in other words, crime in America was nearly halved -- and this even as the population grew by more than 75 million. Since the mid-1990s, the plunge in violent crime has been especially steep: from more than 51 crimes of violence per 1,000 US residents in 1994 to 21 in 2005 -- a 59 percent reduction.

Research analyst Ashley Nellis, lead author of the Sentencing Project's new report, concedes that it is "intuitive" to attribute the striking reduction in crime to the fact that many more criminals are behind bars. But some researchers, she told me yesterday, have determined that incarceration rates account for no more than one-fourth of the drop in crime. Among those she mentioned was economist Steven Levitt, who is known for his controversial Freakonomics argument that the legalizing of abortion in the 1970s helps explain the crime reduction of the 1990s.

Yet even Levitt has estimated that for each additional criminal locked up, there is "a reduction of between five and six reported crimes." In a 2004 paper, he identified "increases in the prison population" as more significant than any other factor in explaining the drop in homicide and other violent crimes. The Sentencing Project may insist that incapacitating criminals through more and longer prison sentences has "made little impact on crime," but those prison sentences have spared countless Americans from being assaulted, robbed, raped, and murdered.

Nowhere in "No Exit" is there any breakdown of the crimes that led to the 140,000 life sentences now being served. Yet the report devotes almost obsessive attention -- including five statistical tables -- to the alleged racial disparity those sentences reflect. About 48 percent of lifers are black, 33 percent are white, and 14 percent are Hispanic. "These figures are consistent with a larger pattern in the criminal justice system," the report notes, "in which African Americans are represented at an increasingly disproportionate rate across the continuum from arrest through incarceration."

Yet the report mentions only in passing another striking disparity: Nearly 97 percent of inmates serving life terms are men. If it is noteworthy that blacks, who account for 12 percent of the general population, make up 48 percent of lifers, shouldn't it be even more significant that men, who comprise less than half the population at large, represent nearly all those sentenced to life?

The explanation, of course, is that men commit the vast majority of serious crime; that hard fact, not sexism, explains the disproportionate male incarceration rate.

Likewise the racial disparity: Though blacks account for just one-eighth of the US population, they are six times more likely than whites to be murdered, and seven times more likely to commit murder. That hard fact, not racism, explains the high proportion of lifers who are black. But such inconvenient facts appear nowhere in the Sentencing Project's report. "No Exit" brims over with information and statistics -- but only the ones that reinforce its sponsor's preconceived views.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe. To follow him on Twitter, click here.)