TO HEAR Smithsonian Institution Secretary Michael Heyman tell it, all that really marred the exhibit scheduled for the 50th anniversary of the Enola Gay's bombing of Hiroshima was its ambition.

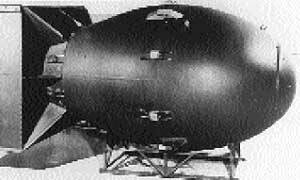

The atomic bomb, nicknamed "Fat Man," that was dropped on Nagasaki |

The "fundamental flaw" to which Heyman alluded was not the blinkered revisionism crystallized in a statement that was part of the exhibit's original text: "For most Americans, this . . . was a war of vengeance. For most Japanese, it was a war to defend their unique culture against Western imperialism." His "regrets" were not over the decision to portray Japan as the chief victim in the Pacific and America as the chief aggressor.

No -- Heyman was simply sorry that the Smithsonian had tried to do too much. "We made a basic error in attempting to couple a historical treatment of the use of atomic weapons with the 50th anniversary commemoration of the end of the war."

Talk about missing the point.

But then, missing the point -- and ending up with politically correct absurdities and diatribes -- is becoming a Smithsonian specialty. Its 1991 exhibit on the American West depicted the pioneers as murderous brutes. Its recent television documentary on New Guinea cannibals commented admiringly that Americans "can learn from people like this."

The Smithsonian's newest exhibit -- "Science in American Life" -- manages to cover nonscience bunkum like phrenology, the racist misuse of IQ tests, society's failure to encourage girls to become scientists, DDT and -- naturally -- mushroom clouds and radiation burns. What it omits, writes the Washington Post's Joel Achenbach, is "the point that science and technology meant, for millions of people, liberation from backbreaking manual labor, from drudgery, from worrying that your child would die or be crippled by polio."

Both houses of Congress are planning hearings on the Smithsonian's operations. Perhaps these will shed light on the intellectual termites that are eating away at the institution's integrity.

Meanwhile, Heyman's remarks sent me back to the letters I received last summer following a column on the Enola Gay exhibit. The bombing of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, I'd written, had made the world a better place. Many readers wrote with memories. A tiny sample:

Gerard Bruggink, Skipperville, Ala. -- "I was one of many POWs whose lives were saved by the atomic blasts. I was part of a group of 400 prisoners who had to build defensive structures on a Japanese airfield in East Thailand. Our small camp was surrounded by antiaircraft guns. On three corners there were also machine-gun positions pointing toward the camp. The first drop of Allied paratroops would have sealed our fate. Fortunately for us and millions of other people, the bombs brought the Emperor to his senses."

George Duffy, Seabrook Beach, N.H. -- "In April 1945, I was a prisoner of the Japanese, building a railway through the jungle of central Sumatra. In my diary of April 27, I wrote, 'Another two months and they'll not be able to bury the dead fast enough.' On the 30th I wrote, 'Deaths in this camp for the month totaled 106.' For the record, 692 prisoners of war died during the construction of this 137.5-mile railway. The bombs put a halt to the misery."

John Hagan, Stamford, Conn. -- "I can attest: I was an infantry platoon leader (89th Div., 354th Reg., L Co.) who luckily survived combat in Europe and who was slated to participate as part of the Japan invasion. I thank God every day for Harry Truman and the atom bomb."

William Arrington, Orrville, Ala. -- "I was a rifleman in the 2d Marine Division, on the east coast of Okinawa. We were sitting ducks in LSTs, Higgins boats and amphibious tractors for days, drowning Nip Zeros and Kamikaze pilots. I can't say how long we were there; each day seemed like forever. After the second bomb was dropped, our division was sent to Kyushu to disarm the Imperial Marines, which were headquartered there. The pumpkin dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki saved hundreds of thousands of American GIs. I saw many gun emplacements all along the coast, indicating a strong defense against amphibious assaults on the beaches."

Don Lindstrom, Oregon, Wis. -- "In July 1945 we received notice that our ship was to make ready for sailing to an Okinawa massing of the Pacific fleet. I would have been directly in on the first-invasion carnage, had it been necessary. I thank everyone from President Truman on down for the dropping of the A-bombs. They cut short the war. My wife, four children, and nine grandchildren would not be here today had I not survived."

Doris Conway, Scranton, Pa. -- "Yes, we did dance for joy when the bomb was dropped, we who had a loved one returning. But it was more than that. We understood that our way of life and liberty had been threatened. It makes me wonder who's running the Smithsonian."

Me too, Mrs. Conway. Me too.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.)