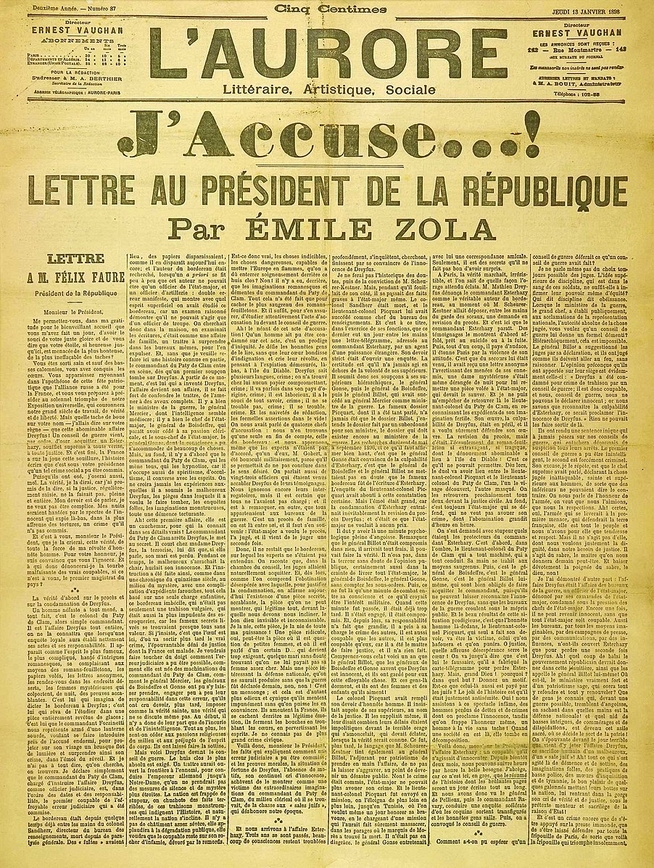

IT IS arguably the most famous front page in the history of journalism. Its one-word headline — "J'accuse...!" — is if anything even more renowned. On Jan. 13, 1898, the French newspaper L'Aurore published Emile Zola's extraordinary 4,000-word open letter on the Dreyfus Affair, a travesty of justice in which an innocent captain in the French army, Alfred Dreyfus, was convicted of treason and sentenced to solitary confinement for life on Devil's Island, a hellish penal colony off the coast of South America. Zola was then the most popular writer in France, and his impassioned essay defending Dreyfus and accusing the military court and the French government of a massive cover-up electrified the nation and reverberated around the world.

Zola's Page 1 article — part investigative reportage, part impassioned advocacy — is on display at Boston University's 808 Gallery, one of scores of documents, cartoons, and artifacts that make up "The Power of Prejudice: The Dreyfus Affair," an exhibition sponsored by the BU Hillel House and Boston's New Center for Arts and Culture. The Dreyfus saga was the first legal ordeal to trigger a media feeding frenzy, and to view "J'accuse!" more than a century after it appeared is to confront the birth of something the modern world takes for granted — the power of the press to galvanize and shape public opinion.

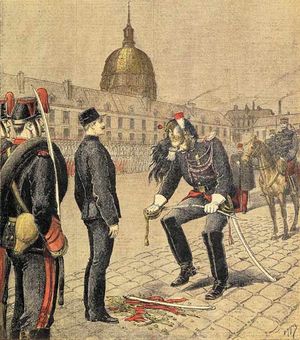

The Dreyfus case began with the discovery of a letter offering to sell French military secrets to the Germans. After an inept investigation, the military intelligence chief, an outspoken antisemite, fingered Dreyfus, the only Jew on the army's General Staff. In truth, Dreyfus was an ardent French patriot, whose boyhood ambition had been to serve his country in uniform. A secret court martial convicted Dreyfus on the basis of a falsified dossier, and in a humiliating public "degradation" at the Ecole Militaire, he was stripped of his decorations and his sword was broken. As Dreyfus loudly protested his innocence, the historian Paul Johnson writes, "an immense and excited crowd ... was beginning to scream, 'Death to Dreyfus! Death to the Jews.'"

The 'degradation' of Alfred Dreyfus on January 5, 1895. The mob cried 'Death to the Jews!' |

Within months a new intelligence chief had identified the real villain, Major Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy. Supporters of Dreyfus — the Dreyfusards — demanded that the case be reopened, but high-ranking officers, determined to shield the army from embarrassment, conspired to protect the traitor. In a sham court-martial, Esterhazy was acquitted. It was in response to that second travesty that Zola wrote "J'accuse...!"

All this was played out against a wave of anti-Semitic hysteria, much of it fueled by the press. Among the most chilling items in the BU exhibition are posters, headlines, and caricatures depicting Jews as snakes, vermin, and hook-nosed swindlers, a filthy race from which France must be cleansed. One giant poster urges voters to support Adolphe Willette, unabashedly campaigning for municipal office as the "Candidat Antisemite." The Dreyfus Affair set off the first great wave of modern political antisemitism, a forerunner of the Nazi terror that would devour Europe a few decades later.

Zola's article mobilized the Dreyfusards, who included many of the era's leading writers, artists, and academics. This too was the birth of something the modern world takes for granted: an intellectual class actively engaged in a war over national culture and values. To the supporters of Dreyfus, the stakes were those of French democracy and justice: individual rights, due process, equality under the law. The anti-Dreyfusards feared the loss of social stability, clerical influence, and French tradition.

The battle raged for a dozen years, cleaving French society, and irrevocably changing the 20th century. Dreyfus was eventually freed and exonerated, reinstated as an officer and publicly decorated with the Legion of Honor. His patriotism undimmed, he saw active duty in World War I, then lived quietly in retirement until his death in 1935.

The effects of the Dreyfus Affair lived on long after Dreyfus was laid to rest. The anti-Semitism it roused was institutionalized, the anti-Dreyfusards in time becoming the pro-fascist core of the Vichy regime. The Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl, stunned by what he saw during Dreyfus's "degradation," went on to write "The Jewish State," the book that launched modern Zionism.

But of all that the Dreyfus Affair set in motion, it is the ascendancy of the press that has, for good and ill, most shaped modern life. "J'accuse...!" Zola wrote, and a new age was born.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter