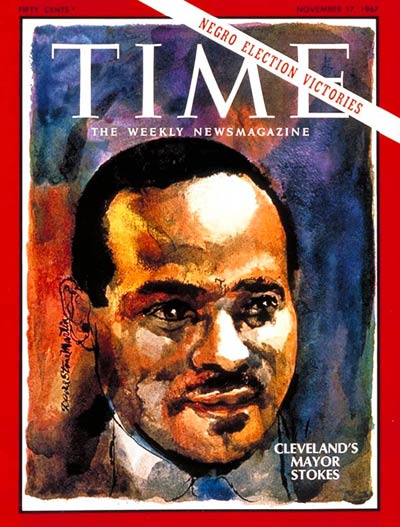

NO HISTORICAL MOMENT could ever capture in its entirety the promise of American equality. But if you had to choose just one date, you could do worse than pick Nov. 7, 1967. It was on that Election Day in Cleveland 40 years ago that Carl B. Stokes, the great-grandson of a slave, became the first black mayor of a major American city by defeating Seth Taft, the grandson of a president.

Today, the National Conference of Black Mayors has close to 50 members, including the chief executives of Philadelphia, Detroit, Washington, Atlanta, and Columbus. At a time when a black US senator is running for president, the State Department is led by its second consecutive black secretary, and the incumbent governor of Massachusetts is a former black kid from Chicago's South Side, the election of a black candidate to a Rust Belt mayor's office may seem like decidedly small potatoes.

In 1967, it was huge.

American blacks were still second-class citizens 40 years ago. Landmark civil-rights laws had been passed, but racism still ran deep and millions of blacks lived in unspeakable squalor. In one city after another, racial rioting turned "long, hot summers" deadly; Cleveland's black Hough district had exploded in the summer of 1966, and the Glenville neighborhood would blow up in 1968. Here and there, black politicians had been elected to legislative or judicial office. But none had managed to win the top job in a significant American city.

Stokes was an urbane and charismatic lawyer, "stage-handsome," as Time magazine described him in a 1967 cover story, and given to "expensively tailored, double-breasted pin-stripe suits, monogrammed shirts, and Antonio y Cleopatra cigars." But he had grown up in grinding poverty in a Cleveland slum. He was a toddler when his father, a laundry worker, died, and "for the next 11 years," Time recalled, "Carl, his older brother Louis, and their mother shared one bed and one bedroom with the rats. While Mrs. Stokes . . . worked as a maid by day, their grandmother reared the boys. But Mother Stokes managed to get across one important message: 'Study, so you'll be somebody.'"

It took Stokes a while to decide that what he wanted to be was a politician. A stint in the Army was followed by turns as a liquor inspector, a probation officer, and a assistant prosecutor. In 1962, he made his first run for office, becoming the first black Democrat elected to the Ohio Legislature. Three years later he ran for mayor, and, in a four-man race, came within a whisker of defeating the incumbent, Ralph Locher.

It took Stokes a while to decide that what he wanted to be was a politician. A stint in the Army was followed by turns as a liquor inspector, a probation officer, and a assistant prosecutor. In 1962, he made his first run for office, becoming the first black Democrat elected to the Ohio Legislature. Three years later he ran for mayor, and, in a four-man race, came within a whisker of defeating the incumbent, Ralph Locher.

It was the first time any black candidate anywhere had come close to taking power in a predominantly white city -- Cleveland, then the nation's 10th-largest municipality, was 65 percent white -- and the effect on the black community was exhilarating. During a parade, Stokes later wrote, he and his wife rode in a convertible past Central High School, where "a group of black kids yelled and waved at us. . . One of the smaller boys jumped up in the air and shouted, 'He's colored, he's colored!' Then he ran down the street, skipping and clapping his hands, yelling, 'He's colored, he's colored, he's colored!' That little boy felt, perhaps for the first time in his life, black pride."

Two years later, when Stokes challenged Mayor Locher in the Democratic primary, his strategy was to generate a massive black turnout, while reassuring white voters that "this is not a Black Power takeover." In 1965, he had campaigned almost exclusively in black wards on the city's East Side; this time he went out of his way to speak to voters on the nearly all-white West Side. Black militants helped too, spreading the word to "cool it for Carl" so there would be no repeat of the violence in Hough a year earlier.

Democratic reactionaries, on the other hand, were alarmed. The Cuyahoga County Democratic Committee distributed flyers warning that if Stokes won, Martin Luther King -- a "noted racist" -- would "actually be the mayor of Cleveland." Stokes wasn't above playing a version of the race card himself. His campaign ran full-page ads proclaiming in large type: "DON'T VOTE FOR A NEGRO." In smaller type underneath, the message continued: "Vote for a man. Vote for ability." On primary day, Stokes breezed past Locher, setting up the general election race against Taft, a gentlemanly Republican and scion of a distinguished political family.

It was a closely fought race that went down to the wire on a snowy Election Day. As expected, Stokes drew more than 90 percent of the black vote, but nearly one in five whites went for him too. When the final tally was in, Stokes had won by just 1,644 votes -- but he had won. A troubled city voted, and history turned on its hinge: Voters black and white had chosen to put an African-American at the helm of a largely white US city. "I can say to you," Stokes told his followers, "that never before have I known the full meaning of the words 'God Bless America.'"

Then as now, the journey to a more perfect union was far from over. But 40 years ago this week, it took a powerful step forward.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.)

-- ## --