AT THE stroke of midnight on Jan. 1, New Hampshire stopped taxing interest and dividends. At that moment, the Granite State — which has never imposed a tax on wages — became a true no-income-tax state, one of only eight in America.

That means that one of the best things about living in Massachusetts — its proximity to New Hampshire — is now even better.

New Hampshire is not the lowest-taxing state in the union, but it has by far the lightest tax burden in the Northeast. It also boasts a more favorable return on investment than any other state. As Andrew Cline of the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy in Concord, N.H., recently wrote, "We get very high quality services at a relatively low cost."

Is it any wonder that so many Massachusetts residents yearn to live in New Hampshire? "In the Granite State, ordinary citizens are entrusted with considerable authority and government is restricted," I wrote in a 2023 column. "In the Bay State, by contrast, residents are allowed only what the state permits — and woe to those who buck the system." Moreover, New Hampshire is safer than Massachusetts, it imposes fewer regulatory burdens, and it has two competitive political parties. All that, and lower taxes too.

Former Massachusetts residents now account for more than 25 percent of New Hampshire's population. |

For years, Massachusetts has been forfeiting more residents to other states than it attracts from other states. As far back as December 2003, a study co-produced by MassINC and the University of Massachusetts warned: "Massachusetts has been losing in the competition for people. ... [T]he rate of loss has been accelerating over the last five years." Two decades later, the picture is no prettier, especially with regard to New Hampshire. Between 2018 and 2022, according to the Census Bureau, 22,047 Massachusetts residents moved to New Hampshire — significantly more than the 19,189 who moved to Florida, the 18,933 who went to New York, or the 14,818 who relocated to California. By now, so many Bay Staters have pulled up stakes and headed north that former Massachusetts residents account for more than 25 percent of New Hampshire's population. In 2021 and 2022, notes demographer Kenneth Johnson, nearly 44 percent of migrants to New Hampshire came from Massachusetts.

People move for all kinds of reasons, of course, but it would be hard to deny that what prompts so many to abandon Massachusetts and make a new start in New Hampshire is its lower cost of living and its much lighter tax burden. "With no income or sales tax, New Hampshire's tax burden is a fraction of what it is in Massachusetts," the Boston-based Pioneer Institute noted in July 2022. The contrast between the two states' approach to taxes grew even sharper later that year, when Massachusetts voters unwisely approved a steep annual income surtax on earnings above $1 million, which raised the top marginal tax rate in the state to 9 percent.

Now New Hampshire has upped the ante. It has scrapped its last vestige of taxation on investment income and given tax-weary Massachusetts residents even more reason to flee. As the Bay State gradually reassumes its former "Taxachusetts" character, New Hampshire offers a very different environment. Are you thinking of leaving the former for the latter? If so, you have plenty of company.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

When politicians defy the courts

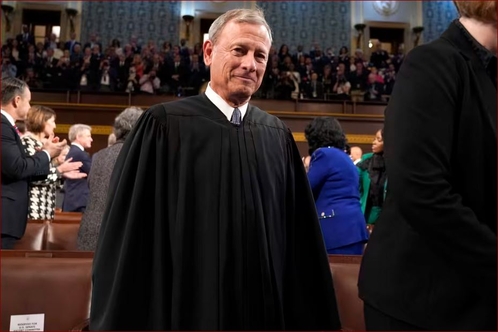

Controversial decisions by the Supreme Court have always generated anger and criticism from disappointed litigants. Through more than two centuries of American history, however, even the most unpopular rulings have nearly always been deferred to. But that norm has lately come under attack — and Chief Justice John Roberts is worried.

"It is not in the nature of judicial work to make everyone happy," Roberts writes in his year-end report on the federal judiciary. "Most cases have a winner and a loser. Every administration suffers defeats in the court system — sometimes in cases with major ramifications for executive or legislative power."

Presidents, congressional leaders, civic leaders, and powerful interest groups have traditionally made their peace with high court rulings they didn't like. President Harry Truman bowed to the Supreme Court's decision that he had no authority to seize the steel mills. New York's Board of Regents eliminated prayer from public schools when the court ruled them unconstitutional. President George W. Bush abandoned plans to try 9/11 detainees before military commissions after the justices concluded that they were unlawful. For 50 years, opponents of abortion accepted that the states had to abide by Roe v. Wade — and once it was overruled in 2022, even the most fervent supporters of abortion on demand conceded that the legal landscape had changed.

In his year-end report, Chief Justice John Roberts decries the increasing defiance of court decisions by political leaders. |

"Within the past few years, however, elected officials from across the political spectrum have raised the specter of open disregard for federal court rulings," Robert observes with concern. "These dangerous suggestions, however sporadic, must be soundly rejected."

The chief justice's essay discusses several forms of what he calls "illegitimate activity" that undermine the judicial independence essential to a society governed by law. For example, there has been a sharp rise in violent threats and intimidation aimed at state and federal judges: Roberts cites the Wisconsin and Maryland judges who were killed at their homes in 2022 and 2023. "In extreme cases," he reports, "judicial officers have been issued bulletproof vests for public events."

Appalling as that is, at least no reputable official defends such violence or threats of violence. The same can't be said of another threat to the judiciary that Roberts highlights: "defiance of judgments lawfully entered by courts of competent jurisdiction." Rarely in US history have the political branches flatly refused to abide by court orders, especially those issued by the Supreme Court in its role as the final arbiter of constitutional and statutory interpretation. But such defiance is now growing increasingly overt — and it's coming from both sides of the political spectrum.

Though the chief justice mentions no names, he may well have been talking about JD Vance, the vice president-elect, who — as part of his metamorphosis from Never Trump stalwart to blind Trump loyalist — has claimed that "the president has to be able to run the government as he thinks he should" and that Supreme Court decisions must not be allowed to get in his way.

"If I was giving [Trump] one piece of advice," Vance said in 2021, it would be to "fire every single mid-level bureaucrat, every civil servant in the administrative state. Replace them with our people. And when the courts — because you will get taken to court — and when the courts stop you, stand before the country like Andrew Jackson did and say: 'The chief justice has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it.' "

Or perhaps the chief justice was alluding to President Biden, who brazenly proclaimed on more than one occasion that he would not let Supreme Court rulings block him from doing what he wanted to do.

Thus, when the high court in 2023 ruled that Biden had no authority to unilaterally write off $430 billion in student loans, the president said he would "stop at nothing to find other ways" to get what he wanted. He later sneered: "The Supreme Court blocked it, but that didn't stop me."

Then again, Roberts may have been referring to President-elect Donald Trump, who, as George Mason University law professor Ilya Somin remarks, is "the biggest elephant in the room" when it comes to denying the legitimacy of court rulings.

Following Trump's defeat in the 2020 election, he filed more than 60 lawsuits in multiple jurisdictions claiming that he was the victim of electoral fraud. Again and again, those claims were found to be without merit — sometimes in rulings handed down by judges Trump had appointed. "Yet instead of accepting these decisions," Somin writes, "Trump tried to use a combination of force (instigating and leveraging the January [2021] attack on the Capitol), and fraud (the fake elector schemes and other shenanigans) to stay in power. ... [I]f courts consistently reject your claims that you have a legal right to X (here, victory in the election), and you resort to force and fraud to try to take X anyway, that's pretty clearly defiance of judicial rulings."

All of these add up to a dangerous trend. If leading political figures continue to openly disregard court rulings, America will be finished as a nation under law. All that will matter is political muscle and which side in a controversy can mobilize more of it. That prospect ought to frighten anyone, liberal or conservative, who loves this country and reveres its constitutional order.

None of this is to suggest that judicial decisions, even those of the Supreme Court, are holy writ that cannot be criticized. It is perfectly legitimate to respond to a court ruling by assembling a litigation strategy designed to curb its scope or to bring about its overturning. That is what civil rights activists did in the decades following Plessy v. Ferguson, what prolife activists did in the decades following Roe v. Wade, and what labor-reform activists did in the decades following Lochner v. New York.

It was also the approach adopted by Abraham Lincoln after the Supreme Court's execrable holding in Dred Scott v. Sandford, widely regarded as the worst court ruling in US history. Lincoln was unsparing in his condemnation of the ruling, which held that people of black African descent were not entitled to any of the rights and privileges of American citizenship. He called it a corrupt and false misreading of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, and warned that it would lead to the spread of slavery into the free states.

But he never urged anyone to defy the court. Instead, he called on his supporters to work for the reversing of Dred Scott. "We know the court ... has often overruled its own decisions, and we shall do what we can to have it overrule this," Lincoln said. In his First Inaugural Address in 1861, he explained how Americans ought to approach even deeply flawed Supreme Court decisions:

I do not forget the position assumed by some that constitutional questions are to be decided by the Supreme Court; nor do I deny that such decisions must be binding in any case upon the parties to a suit as to the object of that suit... . And while it is obviously possible that such decision may be erroneous in any given case, still the evil effect following it, being limited to that particular case, with the chance that it may be overruled and never become a precedent for other cases, can better be borne than could the evils of a different practice.

In other words, even terrible judicial decisions must be respected as binding upon the parties to the specific case, but they need not be accepted as infallible when it comes to national policy. Bad decisions are not immune from further challenge. But any such challenge must follow the rule of law.

Lincoln did not say with contempt, 'The chief justice has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it." He said that Dred Scott must either be overruled in a subsequent case or nullified by changing the Constitution. (Eventually it was undone by the 14th Amendment.) Lincoln was firmly committed to the rule of law. If only the same could be said of Biden, Trump, and Vance.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "What Jane Swift doesn't understand: It's about ethics," Jan. 10, 2000:

Lieutenant Governor Jane Swift has no doubt that the staffers she has pressed into providing day care for her daughter, Elizabeth, are only too glad to volunteer their services.

"I would be stunned if there was anyone who was feeling pressure to spend time with her and care for her," says Swift. To prove the point, she offers a compelling argument: Elizabeth is "adorable and engaging and she's learned to blow kisses." Well, I've got a little one who is adorable and engaging and a pretty skilled kiss-blower himself, and I really need a baby sitter next Wednesday. Would Swift mind getting one of her staffers to "volunteer" a few hours that night to take care of my son? I, too, would be stunned if any of them objected.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"He drew a deep breath. 'Well, I'm back,' he said." — J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (1955)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read something different? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.