KAMALA HARRIS is running the vaguest, most vacuous presidential campaign in modern American history. On issue after issue, she will not take a position. In the very few interviews she has done, her answers to most questions have lurched, as Andrew Sullivan put it the other day (in the course of endorsing her), "from canned phrases to puréed pablum." Harris says emphatically that her "values have not changed," which may be why she is largely unwilling to spell out how those values would translate into policy. Better, she and her strategists figure, to get elected on the strength of not being a paranoid narcissist blowhard like Donald Trump or a faltering old man like Joe Biden. There will be plenty of time for specifics if and when she gets elected.

So it is curious that one of the few clear stands she has embraced as a candidate for the White House is something over which presidents have no authority: the Senate filibuster.

In an appearance on Wisconsin Public Radio last week, Harris endorsed scrapping the Senate rule under which major legislation can be blocked unless a three-fifths majority — 60 senators — agrees to invoke "cloture" and cut off debate.

"I think we should eliminate the filibuster for Roe," she said, "and get us to the point where 51 votes would be what we need to actually put back in law the protections for reproductive freedom and for the ability of every person and every woman to make decisions about their own body and not have their government tell them what to do."

Harris wants to abandon the longstanding institutional consensus that restrains a bare Senate majority from riding roughshod over minority opposition. That would effectively turn the Senate into a second House of Representatives, where the minority party has almost no bargaining power and debate is rigorously curtailed.

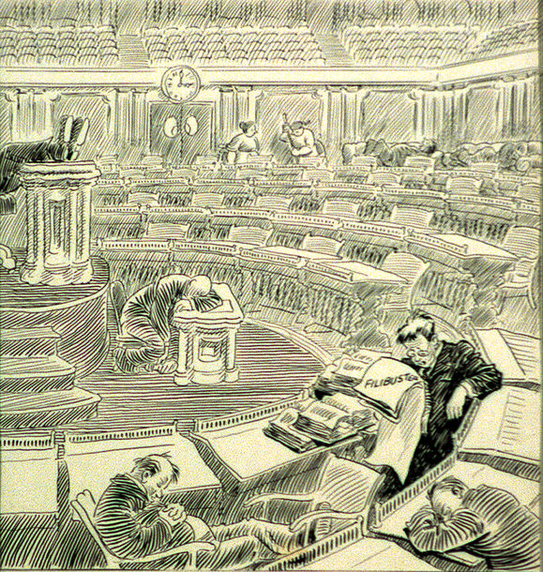

A humorous 1928 cartoon depicting a Senate filibuster by artist John T. McCutcheon. In truth, filibusters were vanishingly rare when senators had to be present, holding the floor and speaking for hours. |

Procedurally, it wouldn't be hard to eliminate the filibuster. All it takes is a majority of senators agreeing to make the change. Democrats control 51 seats in the current Senate, but they haven't been able to blow up the filibuster because two members of their caucus — Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona — have refused to go along with the change. Their refusal is based on principle: No matter which party is in the majority, they support the Senate norm that any significant legislation must have some minority buy-in.

On Sept. 24, Manchin, exaggerating for effect, called the filibuster "the holy grail of democracy," characterizing it as "the only thing that keeps us talking and working together."

A few years ago, one of Manchin's former colleagues, also a Democrat, defended the filibuster in similar terms. Any attempt to blow it up, that colleague maintained, would "curtail the existing rights and prerogatives of Senators to engage in full, robust, and extended debate." That Democratic senator? Kamala Harris. Those words were written in 2017, when Donald Trump was president and he angrily demanded that Republicans — who had a narrow majority in the Senate — tear up the filibuster so he could get his priorities passed. It was then that Harris signed a bipartisan letter defending the filibuster. But her position flipped once the roles were reversed. With Democrats in control of the White House and the Senate, Harris is no longer interested in full, robust, and extended debate. She is interested only in passing a law to protect abortion nationwide.

Needless to say, if the filibuster is uprooted for abortion rights, it will be uprooted for everything. With Manchin and Sinema leaving the Senate in January, no Democrat will agree to reimpose it. Especially if that would mean thwarting the passage of other progressive priorities — enlarging the Supreme Court, say, or statehood for the District of Columbia, or a "wealth" tax on unrealized gains, or a nationwide ban on right-to-work laws. Of course, if Harris is elected president but Republicans win a narrow Senate majority, her eagerness to pull the plug on the filibuster will vanish.

There is an honest, principled argument to be made for opposing the filibuster in its current form, an argument not tied to mere partisan power struggles. The real problem with the rule is that its use has been degraded into something routine and automatic — a default setting that blocks any legislation from passing with less than 60 votes. That was not how the filibuster traditionally operated.

A quick history lesson:

Beginning in the 19th century, any senator or group of senators could indefinitely block a vote on a bill the way Jimmy Stewart did in "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington" — by taking the floor to speak and refusing to stop until the majority agreed to give ground (or the speaker gave up from exhaustion). While a filibuster was underway, all other Senate business came to a halt. In 1917, the rule changed in one critical detail: A filibuster could be stopped if two-thirds of the Senate voted to end debate.

But all that was altered after 1970, when then-Majority Leader Mike Mansfield introduced a "two-track" system, under which a bill being filibustered would be set aside so the Senate could take up other matters. Mansfield expected that the change would make filibusters less desirable by stripping them of their power to gridlock the Senate. Instead, the number of filibusters skyrocketed. Senators quickly realized that all they had to do was announce their intention to filibuster such-and-such a piece of legislation. With no further effort on their part, it would take a supermajority to move the bill forward. The required threshold was reduced from two-thirds to 60 in 1975. Before long it was taken for granted that every bill needed 60 votes to pass.

In short, although the filibuster continues to exist in name, its raison d'être has been totally inverted: A parliamentary rule adopted to ensure debate while encouraging compromise has become an artificial gimmick to prevent debate. Along with the toxic partisanship that today dominates our politics, the modern filibuster's impact has been to make the Senate more dysfunctional and less deliberative.

The solution to this problem isn't to eliminate filibusters. It is to eliminate the two-track system that made them ubiquitous. Senators were far less likely to undertake a filibuster back when they knew that doing so would bring the Senate to a halt. It was a weapon used sparingly. During the entire 19th century there were only 23 filibusters. In the last quarter-century there have been nearly 2,000.

The Senate can make filibusters rare again by making them real again. A determined minority should have the ability to resist passage of a measure its members find intolerable. But they should have to demonstrate their resistance the hard way — by taking the floor, staying on their feet, speaking without letup, and facing the consequences. Only then should it require a supermajority to cut off debate, while other bills and motions could be advanced with a simple 50 percent plus 1.

True filibuster reform does not mean turning the Senate into a second House. It means bringing the old filibuster back. But where are the candidates who will say so?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The voice of the shofar

The most evocative sound in Jewish life will resound this week in synagogues the world over with the arrival of Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year. During the synagogue service, a shofar — a curved, hollowed-out ram's horn — is sounded 100 times. In normative Jewish law, hearing those sounds is an affirmative biblical commandment, much like fasting on Yom Kippur and eating matzah on Passover. Indeed, in the Hebrew Bible the holiday is not referred to as the new year. It is called "a day when the horn is sounded."

In the long, long history of the Jews, the blast of the shofar has been the quintessential sound. To quote the late Jonathan Sacks — Great Britain's longtime chief rabbi, a member of the House of Lords, and an admired public intellectual — the shofar emits "the wordless cry at the heart of a religion of words." Jews, the people of the book, have always been absorbed with texts, arguments, commentaries, and scholarship. Perhaps no culture has ever been more verbal. "Yet there is a time for emotions that lie too deep for words," wrote Sacks, whose writings I draw on in what follows. "The sound of the shofar breaks through the carapace of the self-justifying mind and touches us directly, at the most primal level of our being."

But what does the sound mean? What is that "wordless" message Jews are supposed to take to heart at the start of each year?

Tradition offers multiple answers.

Rabbi Shlomo Goren, chief rabbi of the Israel Defense Forces, sounded a shofar at the Western Wall in June 1967, marking the moment when Jerusalem's Temple Mount returned to Jewish control for the first time in 19 centuries. |

To begin with, it is a clarion sounded at the coronation of the king. There are multiple biblical references connecting the ram's horn to royalty — for example, I Kings 1:39: "Then they sounded the shofar and all the people shouted, 'Long live King Solomon!' " A key theme in the Rosh Hashana service is God's kingship — the date is said to mark the anniversary of the creation of mankind. Unlike other festivals on the Jewish calendar, there is a distinctly universal note to the Rosh Hashana liturgy. Jews pray not only for their own welfare but for that of the whole world, beseeching God to hasten the day when "all wickedness will vanish like smoke" and "the rule of evil will be removed from the earth."

But that is just the start of the shofar's many meanings. Among the others: It is a reminder of the shofar that sounded during the revelation at Sinai, when, according to Exodus, "there was thunder, and lightning, and a dense cloud upon the mountain, and a very loud blast of the shofar" as God proclaimed the Ten Commandments to the assembled Israelites.

The 12th-century Jewish sage Maimonides, a towering giant of Jewish scholarship, understood the sound of the shofar to be an annual wake-up alarm. It is meant to shake people from their complacency — to startle them into self-reflection, prompting them to repent for their sins and to repair their ways and deeds.

The most poetic understanding of the shofar's sound is that it represents human weeping — and, true to Jewish culture, there was a disagreement over what that sound should be. Perhaps it is a long unbroken blast, like the wail of someone in the first throes of grief. Perhaps it is a series of medium-length tones, as of someone sighing or groaning in sorrow. Or perhaps it is a burst of staccato notes, like the repeated sobs of a broken heart. The universal practice became to sound the shofar in all three modes, blowing it during the Rosh Hashana service a grand total of 100 times.

The impact of those tones can be deeply affecting. For more than six decades I have listened as the shofar is blown on Rosh Hashana. The sounds never lose their mesmerizing quality. They are simultaneously stirring and disturbing, powerful and poignant. I doubt that the same effect could be produced by a more splendid and polished instrument. The Bible makes mention of many instruments, including silver trumpets, harps, flutes, and tambourines. The shofar is the least musical of them all. It cannot be tuned, cannot play a melody, cannot be sung or danced to. It is primitive and raw, without elegance or pomp or sweetness. Yet Jews have resonated to its wail and sobs for thousands of years, at times risking their lives to do so.

The shofar was sounded during the coronation of ancient Israelite kings. It was sounded before battle, most famously when Joshua led the people of Israel into Jericho. It was sounded every 50th year to announce the Jubilee and — in the words inscribed on the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia — to "proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof." It was sounded during the Six-Day War in 1967, when Jews regained possession of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, their holiest site, for the first time in 19 centuries.

Sacks suggests that what explains the persistence of the shofar through so many generations is its unadorned plainness. "It is simple, easily available, a natural product, not a manufactured one," he wrote in 2006. "In Jewish history the simple has tended to prevail over the sophisticated, for God seeks the unadorned heart. The very naturalness of the shofar gives it its power."

That power will be felt again this week wherever Jews gather in synagogues, welcoming the year 5785 not with champagne and party hats but with repentance and hope. To the ancient sounds of the shofar, Jewish communities will do what they have done in this season time out of mind: pray that they and all the world may be blessed in the months ahead with life and good health, happiness and peace.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "The joyous arrival of Baby 6 Billion," Oct. 14, 1999:

And baby makes 6 billion. According to the United Nations, the Earth's human population reached 6,000,000,000 this week, a round number by anyone's measure. Where this milestone baby made her appearance no one can say, but it's a reasonable guess that she was welcomed by her parents and siblings the way most new family members are welcomed: joyfully.

Baby 6 Billion's arrival should make all of us joyful. A century ago, the world couldn't even sustain 2 billion human beings. Ten centuries ago, fewer than 500 million could keep themselves alive. For a baby born at the turn of the last millennium, surviving childhood was at best a 50-50 proposition; surviving past 40 was extraordinary. Baby 6 Billion, by contrast, can look forward to 65 birthdays.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"I shall smile when wreaths of snow

Blossom where the rose should grow;

I shall sing when night's decay

Ushers in a drearier day." —Emily Brontë, "Fall, Leaves, Fall" (1846)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read something different? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.