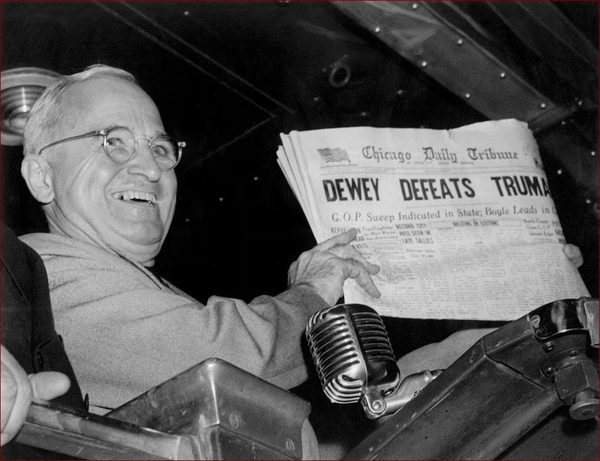

Harry Truman's victory in the 1948 presidential election might have been less surprising if there had been robust political betting markets at the time. |

IF YOU'RE like me, your earliest introduction to the commodities market was the hilarious 1983 film "Trading Places." In an early scene, Billy Ray Valentine (played by Eddie Murphy) is being instructed by the patronizing Duke brothers, Randolph (Ralph Bellamy) and Mortimer (Don Ameche), in the basics of commodities trading.

"We are commodities brokers," Randolph says. "Now, what are commodities?" He indicates several items set out on a desk as visual props, including a cup of coffee, a loaf of bread, and a glass of juice.

"Commodities are agricultural products — like coffee that you had for breakfast; wheat, which is used to make bread; pork bellies, which is used to make bacon, which you might find in a bacon and lettuce and tomato sandwich. And then there are other commodities, like frozen orange juice and gold." The brokerage makes its money, Randolph explains, by buying and selling contracts to supply those commodities, sometimes to clients who speculate that their price will rise in the future, sometimes to clients who expect the price to fall. Valentine, a former street hustler, listens to the explanation and remarks: "Sounds to me like you guys are a couple of bookies."

In truth, futures trading extends far beyond agricultural products like wheat or mineral resources like gold. It is possible today to buy and sell futures contracts (also called derivatives or event contracts) on a vast range of intangible outcomes. Kalshi Inc., for example — a relatively new American prediction market regulated by a federal agency called the Commodity Futures Trading Commission — enables investors to bet on a wide array of future developments. Currently, Kalshi offers markets on dozens of topics, such as whether the Consumer Price Index will rise or fall this month; what the Rotten Tomatoes score will be for the upcoming Ridley Scott movie, "Gladiator 2"; how many tornadoes there will be in June; whether UCLA will cancel its commencement exercises; and how thin Arctic sea ice will be next summer.

If the streetwise character in "Trading Places" thought wagering on orange juice futures was like dealing with a bookie, imagine what he would make of modern prediction markets.

Last month, almost as if it were channeling its inner Billy Ray Valentine, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission voted 3-2 for a new rule forbidding the use of event contracts for betting on national elections. Its purpose, The Wall Street Journal reported, was "to clarify the boundaries between gambling and financial markets." The proposal — still preliminary — would prevent Kalshi from expanding its business into political wagers. It would also force PredictIt, an exchange that does offer markets on the outcome of elections, to shut down that part of its operation.

According to Rostin Behnam, the CFTC chairman, political betting markets must be suppressed because they threaten "election integrity and the democratic process." If wagering on politics is allowed to continue, the commission could find itself obliged to investigate charges of election fraud — an especially unwelcome prospect for a Wall Street regulator given the degree of American polarization. Two activists who agree with him — Dennis Kelleher of Better Markets and Lisa Gilbert of Public Citizen — argued in the Los Angeles Times last week that "to allow betting on elections through the commodities market . . . could unleash a torrent of misinformation" and "create powerful new incentives for bad actors to influence voters and manipulate the results to favor their bets."

But there is little or no evidence to substantiate such fears. To be sure, misinformation has always been a feature of political campaigns and will continue to be with or without political futures contracts. As for inducing "bad actors" to manipulate the results — such vote-tampering is already illegal and would be subject to prosecution. In any case, to shift the outcome of a national election would require a daunting level of coordinated corruption, something far beyond the scope of a crooked county official or polling-place judge.

Many Americans don't know it, but for many decades betting on US politics was commonplace on Wall Street and covered by the nation's political press. "As early as the 1860s," noted The New Yorker in 2022, "American newspapers reported on betting markets pertaining to presidential contests, covering them almost daily as elections neared." A few weeks before the 1924 election, a front-page story in The New York Times reported that betting in the three-way presidential contest among Republican Calvin Coolidge, Democrat John W. Davis, and Progressive Robert La Follette was unusually sluggish. Because Coolidge was such a sure bet to win, there was "a dearth of Davis and La Follette money." The action was livelier in the New York gubernatorial race, where incumbent Al Smith, a Democrat, was only a 7-to-5 favorite over the GOP nominee, Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

The outcome of those elections illustrates the utility of political prediction markets. Coolidge won the election handily, carrying 35 of the 48 states and receiving 54 percent of the vote. The New York race, by contrast, was much closer: Smith was reelected, but he drew a shade under 50 percent of the vote. In both cases, the market forecasts were on target.

In a letter to federal regulators opposing a ban on election betting, a group of self-identified progressive legislators, policymakers, and activists, headed by Democratic Representative Ritchie Torres of New York, strenuously advocated for keeping political futures markets legal because their accuracy can help offset electoral passions.

"Real-world data repeatedly emphasizes the superior forecasting accuracy of prediction markets to polls and pundits," the progressive group emphasized. "Because traders have financial skin in the game, their principal incentive is to predict accurately, instead of merely supporting a partisan line." Besides, they wrote, "there are mountains of data from other countries and in smaller-scale markets . . . that these prices are resilient to manipulation."

Wall Street's once-familiar political betting markets fell out of fashion with the rise of modern scientific polling in the late 1930s. But the polling industry has reeled in recent years as the reliability of survey results have repeatedly been called into question. All the more reason, then, to uphold and expand legal prediction markets, which have a recognized track record of reliability.

In "Trading Places," the crooked Duke brothers try to corner the market on orange juice by exploiting stolen information to manipulate the price. But such trickery is hard to pull off in real-life trading pits, given the oversight of federal commodities regulators. It would be just as hard to pull off in an electoral prediction market — harder, certainly, than if election betting were left to unregulated, offshore, or black markets. In countries where markets to track politics are routine, such as Australia and Great Britain, no such fraud has been reported.

Ultimately, the virtue of political betting markets is that they provide information, and information is always valuable. It is lawful to glean insight on the outcome of an election through political journalism, political polling, political campaigning, and political modeling. Why should political wagering be any different? Americans are free to bet on anything from the World Series to Powerball to real estate to stocks and bonds. Surely they shouldn't lose that freedom when it comes to politics.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.