THE LAST TIME a Nazi or Nazi collaborator was tried in Jerusalem for war crimes, Israel was a very different place. In 1961, when Adolf Eichmann sat in the famous glass booth in Jerusalem District Court, the Jewish state was only 13 years old.

Yet to many, including Israelis themselves, Israel had already assumed legendary dimensions. It seemed natural, somehow, to view Israel as heroic, as a country touched by destiny — to admire its stirring history and passion for democracy, to hail the courage of its founding pioneers and their refusal to be intimidated in the face of implacable enemies.

Even Hollywood got into the act, giving us movies like Exodus and Cast a Giant Shadow. Otto Preminger never made a movie about the birth of Zambia — or even New Jersey. But Israel? That was different. That was the stuff of which screenplays were made — a country where every soldier was Moshe Dayan, and every politician was David Ben Gurion.

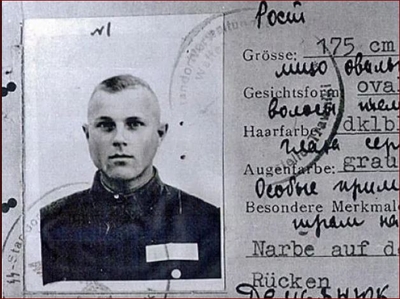

Ivan Demjanjuk's Nasi-issued ID card. |

Against such a background, the Eichmann trial opened. It, too, was cast in epic terms. Good versus Evil. Nazi versus Jew. Six million martyrs versus the mastermind of the Final Solution.

Bringing a powerful Nazi leader to justice was only the simplest of the prosecutors' goals. They intended to use the Eichmann trial to teach a blithe and complacent world what the Nazis had done — and especially to teach the younger generation, the first to grow up since the Holocaust. With a massive and painstaking marshaling of the evidence, they set about to refresh the memory of a world that was already beginning to forget. They aimed to concentrate the attention of every nation on the immensity of the German atrocities.

But something else was accomplished, too. However strong and valiant the Jewish state might have seemed in 1961, the man in the glass booth was a symbol of Israel's grim and desperate origins. If the Israelis, with their chutzpah and panache, sometimes came off as indomitable and larger than life, this trial reminded them that barely a generation earlier, one out of every three

Jews on Earth had been wiped out. Hollywood notwithstanding, the lives of Jews had always been precarious, and underneath all the bravado the state of Israel was a very vulnerable place.

Today, as a new trial unfolds, things have drastically changed. Israel is nearly 40, and showing its age. It's a country fractured by divisions and strife: secular Jews against religious; Ashkenazim against Sephardim; hawks against doves. Political elections give mandates to nobody, and tense coalition governments are formed like shotgun weddings.

Far more than in 1961, Israel is today a secure military power. Yet, ironically, we see Israel now more as a land of decay than of destiny: terrorism, spy scandals, economic chaos, the Palestinians. Israelis see it that way, too: In record numbers, they are leaving their own country.

It's not a lofty picture. And the man in the dock this time is no lofty Nazi officer, coldly organizing death camps and arranging deportation schedules. He is a Ukrainian peasant with the ponderous name of Ivan Demjanjuk, accused of brutally torturing and gleefully killing hundreds of thousands of innocent human beings.

If Adolf Eichmann personified the entire Third Reich, Ivan Demjanjuk personifies only a common Nazi thug – the kind of sadist who stuffed Jews into gas chambers for pleasure.

Should the evidence prove that Demjanjuk is indeed Ivan the Terrible of the Treblinka concentration camp, then he must pay for his crimes. But like the Eichmann trial, this one too can serve an added purpose. It can restore a measure of unity to an Israel that seems these days to be tearing itself apart over everything. In the midst of the Israelis' squabbling and self doubt, the trial of Ivan Demjanjuk holds out something they desperately need: the common identity that binds them.

And when the president of the United States can describe Nazi soldiers buried in a German cemetery as "victims, just as surely as the victims in the concentration camps," or when a would-be president, the Rev. Jesse Jackson, can say, "I am sick and tired of hearing about the Holocaust," it holds out something we need as well.

The Demjaniuk trial, not a moment too soon, is reminding all of us why Israel was created in the first place, and of the ease with ordinary men can become savages.

Jeff Jacoby is a lawyer, political consultant, and free-lance writer in Boston.