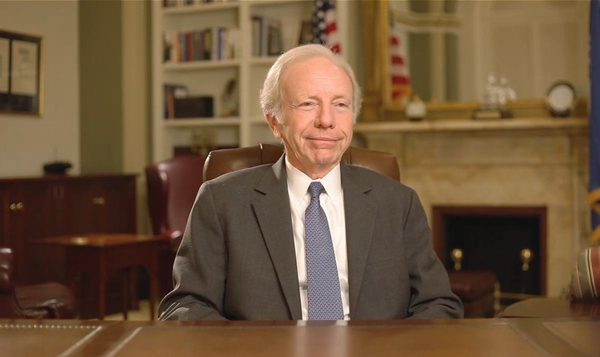

Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut, who served four terms as a US senator and was the Democratic nominee for vice president in 2000, died March 27 at 82. |

IN HIS long political career, Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut, who died last week at 82, was embroiled in any number of controversies. The four-term US senator and 2000 Democratic nominee for vice president was criticized for positions he took on issues ranging from the war in Iraq (which he supported) to explicit sex and violence in popular music (which he opposed). Democratic voters in his state turned decisively against him when he ran for a fourth US Senate term in 2006 — he was defeated in the Connecticut primary by an antiwar candidate, Ned Lamont, and had to run as an independent in the general election to retain his seat.

For all that, Lieberman's death last week was greeted by an across-the-board outpouring of sorrow and appreciation. "Friends, Allies and Even Former Rivals Eulogize Joseph Lieberman," a New York Times story was headlined. Hardline conservatives and ardent progressives, prominent Republicans and renowned Democrats joined in expressing their admiration. One sentiment was repeated again and again: Lieberman had been a "mensch."

The meaning of that word, eulogized Al Gore, the 2000 Democratic presidential nominee who chose the Connecticut senator as his running mate, can be found not "in dictionaries so much as ... in the way Joe Lieberman lived his life: friendship over anger, reconciliation as a form of grace. We can learn from Joe Lieberman's life some critical lessons about how we might heal the rancor in our nation today."

John F. Kennedy once remarked that there were times when "party loyalty asks too much." Lieberman was a loyal Democrat but he was not infected with the polarized inflexibility — my party, right or wrong — that now dominates political life.

In the 2008 presidential campaign, the former Democratic vice presidential nominee endorsed Republican John McCain, believing he could "break through the reflexive partisanship" that has made contemporary politics so poisonous. "Being a Republican is important; being a Democrat is important," Lieberman said. "But you know what's more important than that? The interest and well-being of the United States of America."

Yet politics and policy were not what Lieberman valued most. His religious and moral convictions were. As an Orthodox Jew, he would not ride in a car or use a phone on the Sabbath. As he wrote in "The Gift of Rest," his acclaimed 2011 memoir about keeping the Sabbath, if his presence was required for a Saturday roll call on a vital matter, he would walk 5 miles to the Capitol to cast his vote.

If any single incident in Lieberman's long political career exemplified his refusal to subordinate decency and honesty to political expedience, it was his reaction to President Bill Clinton's extramarital affair with Monica Lewinsky, a 22-year-old White House intern.

Lieberman was a staunch Clinton supporter, a charter member of those known as FOBs, or Friends of Bill. But he was appalled by the president's scandalous behavior and by the fact that Clinton had lied about it for months. He was dismayed as well by the refusal of his fellow Democrats in Congress to publicly address it.

On Sept. 3, 1998, in what Lieberman later called "the hardest thing I've ever done in public life," he took the Senate floor to deliver an extraordinary public condemnation of Clinton's behavior.

He was angry, he said, because all along he had accepted Clinton's denials at face value and felt betrayed when the president finally admitted the truth. But beyond personal dismay, Lieberman expressed anguish over the damage caused to American society by Clinton's conduct.

"I must respectfully disagree with the president's contention that his relationship with Monica Lewinsky and the way in which he misled us about it is nobody's business but his family's," the senator said. Presidents' private lives are public, and there is no getting around it.

A president is not just a high-ranking elected politician, Lieberman stressed; he is emblematic of the American people. "So when his personal conduct is embarrassing, it is sadly so not just for him and his family, it is embarrassing for all of us as Americans." Moreover, the president is a role model. Thanks to "his prominence and the moral authority that emanates from his office," he sets standards that others emulate.

What Clinton had done was worse than "inappropriate," declared Lieberman. It was "immoral" and "harmful."

His blistering words about the president who was both a friend and fellow Democrat triggered a political shock wave. They were on Page 1 the next day in leading newspapers. Lieberman was praised for breaking the Democrats' silence. Even Clinton said he couldn't disagree with the rebuke.

For a politician, few challenges are more daunting than openly criticizing a popular, powerful party leader. Lieberman's words didn't change the country's political dynamic but they were a compelling testament to Lieberman's unshakable integrity. If only men like him were not so rare in political life. May his memory be a blessing.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe. This column is adapted from the current issue of Arguable, his weekly newsletter.

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.