Philip de László was one of the most renowned portrait painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Budapest in 1869, he studied art in Munich, Paris, and Vienna before moving to England in 1907, where he acquired British citizenship and raised a large family in London. László was an extraordinarily industrious artist; he painted some 2,700 portraits over the course of his career. "These included members of the majority of royal houses of Europe, European political leaders, British aristocracy and establishment," observes Britain's National Portrait Gallery on its website. Among the many illustrious subjects who sat for him were Emperor Franz Josef I; Popes Leo XIII and Pius XI; King Edward VII and his wife, Queen Alexandra; and the 8-year-old Princess Elizabeth of York, who would later be crowned Queen Elizabeth II.

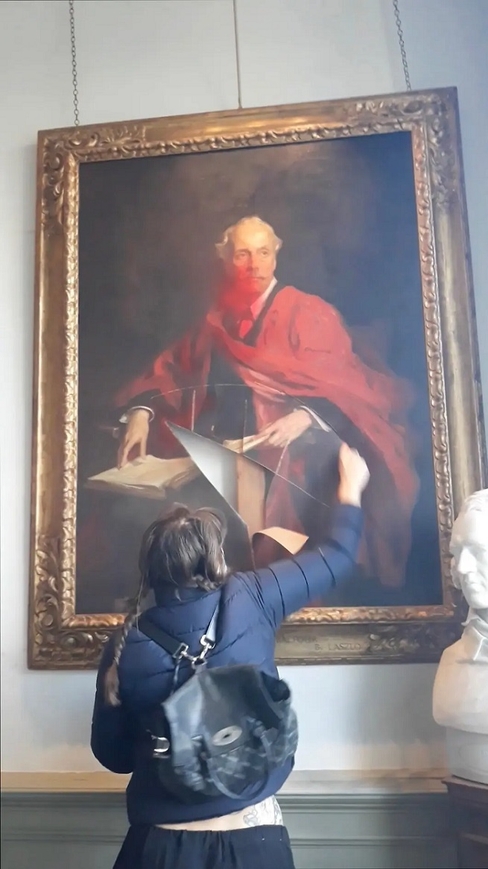

In 1914, László was commissioned to paint Arthur James Balfour. A longtime British statesman and Conservative member of Parliament, Balfour had been prime minister from 1902 to 1905, and would become foreign secretary in the government of David Lloyd George at the end of 1916. The portrait was commissioned by Trinity College, a division of the University of Cambridge, where Balfour had been educated. And it was at Trinity College this month that the painting was severely, perhaps irreparably, vandalized, when an anti-Israel fanatic from the group Palestine Action sprayed Balfour's image with red paint, then used a blade to repeatedly slash the canvas.

On its X account, Palestine Action posted video of the painting's destruction, which it defended on the grounds that "Balfour's declaration began the ethnic cleansing of Palestine by promising the land away — which the British never had the right to do." It then gloated that no one was arrested for the painting's destruction.

Balfour's famous "declaration" was a letter, dated Nov. 2, 1917, expressing support for "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people." At the time, Palestine encompassed not just the land between the (Jordan) river and the (Mediterranean) sea, but a far greater swath of territory east of the river. In 1922, the League of Nations awarded Britain a mandate to govern Palestine, directing it to facilitate the creation of a Jewish homeland. By that point, Britain had already carved away nearly four-fifths of Palestine and proclaimed it a brand-new Arab country, Transjordan (the present-day Kingdom of Jordan). It was just one of many independent Arab countries into which the territory of the former Ottoman Empire would be subdivided. All that was envisioned for the promised Jewish national home was the small fraction of historic Palestine west of the Jordan River.

Using spray paint and a blade, an anti-Israel vandal at the University of Cambridge in England attacked a portrait of Arthur James Balfour, the British foreign secretary who issued the Balfour Declaration. |

But even a tiny Jewish country was more than most Arab leaders were willing to accept. Lethal violence erupted in 1936, whipped up by the fanatically antisemitic Haj Amin al-Husseini, a loyal ally of Adolf Hitler who was determined to prevent Jewish sovereignty in any part of Palestine.

The violence had its intended effect. Britain abandoned Balfour's declaration. In 1939, the government of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain issued orders reducing Jewish immigration into Palestine to a trickle and declaring its opposition to Jewish statehood. Thus, just as Hitler's genocidal Final Solution was getting underway, the gates of the promised Jewish homeland were slammed shut.

In the end, Britain pulled out of Palestine altogether, leaving its fate in the hands of the United Nations. In November 1947, the UN voted to partition Palestine — i.e., the remnant of Palestine that hadn't been turned into Transjordan — into two states, one Jewish, one Arab. The Jews accepted the UN's decision. The Arabs again said no, and launched what they proclaimed would be a "war of extermination" against the new Jewish state on the day of its birth.

The slashing of Balfour's portrait is an apt symbol of the nihilism and malice that have always been the engine of Palestinian nationalism. The building of an Arab state in Palestine was never the goal of the Palestinian leadership. Whereas Zionists beginning in the 1860s had painstakingly, methodically, optimistically worked to assemble the structures a restored Jewish state would need, Arab leaders and militants focused not on setting up a nation for themselves but on preventing Jews from doing so. Decades before there was an independent Israel, Arabs were carrying out violent pogroms against Jews in Palestine. All these years later, they are still doing so — never more savagely than on Oct. 7.

A handful of far-sighted Arab visionaries, such as the Emir Faisal, who was born in Mecca and became king of Iraq, welcomed the Zionist project. "We wish the Jews a most hearty welcome home," he wrote in 1919. "I look forward, and my people with me look forward, to a future in which we will help you and you will help us."

Sadly, he was a rare exception. From the outset, the Palestinian movement was driven by hostility to Jewish sovereignty. The 1988 Hamas charter, like the Palestine National Covenant of 1964, calls for the violent elimination of Israel. The emblem of Fatah (the main Palestinian Authority faction) depicts crossed rifles superimposed on a map of Israel; the Hamas emblem is similar, except that the weapons are swords. Contrast that with Israel's declaration of independence, which appealed directly "to the Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel to preserve peace and participate in the building up of the state on the basis of full and equal citizenship."

The history of Zionism before Israeli statehood is a history of pioneers draining swamps, founding kibbutzim, planting vineyards, establishing schools, raising cities from empty sand dunes, and shaping durable democratic institutions. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose founders included Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, and Chaim Weizmann, opened its doors in 1925. The Palestine Orchestra, a Jewish ensemble later renamed the Israel Philharmonic, was launched in 1936 with the eminent Arturo Toscanini conducting. The first Hadassah hospital, established by Zionists in 1918, made a point of serving Jewish and Arab patients alike, as the British government's Peel Commission reported in 1937. In these and countless other ways, Zionism was a creative, constructive, fertile, positive movement, driven by undying hope and always focused on the objective of reviving Jewish statehood in the traditional Jewish homeland.

That was never the approach of the Palestinian movement.

"The whole of Palestinian nationalism was based on driving all Israelis out," the renowned Palestinian scholar Edward Said told an interviewer in 1999. The two-state solution recommended by the UN in 1947 was rejected out of hand. Nearly eight decades later, little has changed. When Israel offered in 2000 and 2008 to recognize a Palestinian state in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, it was spurned. When Israel in 2005 unilaterally evacuated every Jewish resident from the Gaza Strip and turned the territory — including its thriving network of greenhouses — over to the Palestinian Authority, it was a silver-platter opportunity to show what Palestinian nationalists were capable of creating. Tragically, unforgivably, what emerged was a terrorist enclave devoted to killing as many Israelis as possible.

With the end of Ottoman rule in Palestine, Jews and Arabs had the same opportunity to build for the future. The two communities made very different choices and pursued very different ends. One devoted itself to raising up, the other to tearing down. Those fundamental underlying attitudes have not changed in more than a century, as a demolished painting in Cambridge attests.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Life imitates art: stoned rats

The New Orleans Police Department is having a rat problem. The Times-Picayune reports that the rodents have taken over the department's Broad Street headquarters, leaving feces scattered on employees' desks and devouring narcotics stored in the evidence room.

"The rats are eating our marijuana," police Superintendent Anne Kirkpatrick told city councilors during a hearing last week. "They're all high."

Media accounts describe numerous other failures of maintenance and safety, including broken elevators, plumbing that doesn't work, an air-conditioning system that collapsed last summer, and uncleanliness that is "off the charts." But the superintendent's disclosure of the drugged-up rats seems to have finally gotten City Council's attention and persuaded at least some members to undertake the "Herculean lift" of relocating the NOPD headquarters to an office tower downtown.

New Orleans is far from unique in being plagued by rats. These two were spotted in Boston. |

The Guardian added a little international flavor to the story. In a March 12 story, it resurrected the 2022 case of rats in India eating more than 1,100 pounds of confiscated cannabis being stored in an Uttar Pradesh police warehouse. Four years earlier, the paper reported that a group of police officers in Argentina had been dismissed because officials doubted their claim that mice had eaten more than half a ton of marijuana missing from a police warehouse near Buenos Aires.

What the pothead rats in New Orleans called to my mind, however, was The Nutmeg of Consolation, one of the 20 historical novels in Patrick O'Brian's acclaimed Aubrey-Maturin series, which are set during the Napoleonic wars of the early 1800s. I am an enormous fan of the O'Brian novels, notwithstanding my thorough lack of interest in nautical battles and the workings of sailing ships. (As I mentioned in a column last year, it was Patrick Tull's unabridged recording of the first book in the series, Master and Commander, that first got me hooked.)

In "Nutmeg," Captain Jack Aubrey and his crew — one of whom always includes Dr. Stephen Maturin, the ship's surgeon and Aubrey's close friend — are sailing from the South China Sea to Australia. Several of the men notice an unusual brazenness among the rats on the ship — "how mild in temper they were, and placid, and how they were to be seen wandering about in the day, well above the hold and even the cable-tier." There is speculation that the rodents' aplomb might be explained by "the unnatural cleanliness of the ballast." But within a day or so the rats turn vicious, biting two little girls who tried to make pets of them and engaging in "furious scuffling fore and aft."

Maturin solves the mystery when he goes to the store-room to fetch a few of the Peruvian coca leaves he has gotten into the habit of chewing when his mind is agitated:

The leaves were packed tight in soft leather sausages sewn over with a neat surgical stitch, each in a double oiled-skin envelope against the damp. ... The pouches were in a particularly massive and elegant ironwood chest with intricate Javanese brasswork over its top and sides and although he had heard and seen much of the strange confident behavior of the rats he had no fear of them in this particular instance: Apart from anything else, this store-room was used for wine, cold-weather clothes, books — it had nothing to do with the pantry.

Yet he was not the first sailor to be deceived by a rat. They had gnawed their way up through the very plank, up through the bottom of the chest itself. There was nothing left but rat-dung. Nothing. They had eaten all the leaves and all the leather impregnated with the scent of the leaves and they were clearly eager to get at the chest again, a group of them standing just outside the lit circle of his lantern, waiting impatiently to gnaw at the wood on which the pouches had lain.

In his journal that night, Maturin records his discovery:

For some time the behavior of the ship's rats (a numerous crew) had excited comment, and it is now clear to me that they had become slaves to the coca. Now that they have eaten it all, now that they are deprived of it, all their mildness, lack of fear, and what might even be called their complaisance is gone. They are rats and worse than rats: they fight, they kill one another, and [they emit] harsh strident screams.

As it turns out, coke-addicted rats are the least of the challenging animals that Dr. Maturin, an avid naturalist, encounters in The Nutmeg of Consolation. Near the end of the book — mild spoiler alert — he is elated to encounter the duck-billed platypuses native to eastern Australia. But when he catches one, it sinks its venomous spur into his arm, causing intense pain and delirium.

So count your blessings, New Orleans PD. Rats may be munching your marijuana, but at least a plague of poisonous platypuses is one fate you've been spared.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "Double standards, left and right," March 15, 1999:

The news out of Guatemala has been causing me twinges of self-reproach. Not because what I have written about Guatemala has proved to be wrong. But because I have never written about Guatemala ... where hundreds of thousands of people were dying in a brutal civil war.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown." — T.S. Eliot, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" (1915)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.