Elia Kazan had a choice in 1952: to stand with the communists or to stand against them. He chose to stand against them, and Hollywood's Stalinists have reviled him ever since.

On March 21, Kazan will receive an Oscar for lifetime achievement at the Academy Awards. For the man who launched the careers of James Dean and Marlon Brando, the director of such acclaimed motion pictures as "Gentleman's Agreement," "A Streetcar Named Desire," "On the Waterfront," and "East of Eden," it is an honor long overdue. For years Kazan's enemies have kept him from receiving such awards; he was snubbed by the American Film Institute and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. It reportedly took an impassioned plea by Karl Malden (another Kazan discovery) to break the blackball at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Kazan-haters intend to protest outside the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on Oscar night and would like to see him humiliated — or worse — inside the auditorium when he receives his award. "I'll be watching, hoping someone shoots him," says Abraham Polonsky, who was blacklisted in the 1950s for his communist sympathies. "It would no doubt be a thrill."

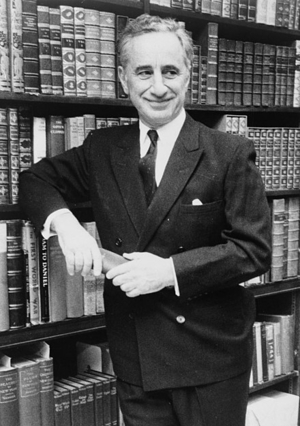

Elia Kazan in 1967 |

The hard Hollywood left supposedly despises Kazan because he "named names" before the House Un-American Activities Committee. In the early 1930s, when he worked for the Group Theater in New York, Kazan had been one of a cell of nine Communist Party members. In his testimony 17 years later, he identified the others, describing how they had been expected to do the party's bidding in the theater world and how they had taken orders from paid party commissars. By 1952 hardly any of this was news. Nor was Kazan the only member of the cell to testify. Playwright Clifford Odets, one of the Group Theater's founders, appeared before the committee a few weeks after Kazan did.

There was no joy in naming names. Kazan detected a "sadistic streak" in the HUAC inquisitors, he would later write, and "concluded that what these fellows were conducting was a degradation ceremony in which the acts of informing were more important than the information conveyed." He wrestled with his conscience before and after his HUAC appearance; as he put it in his autobiography, "here I am, 35 years later, still worrying over it."

But, however distasteful cooperating with the committee may have been, cooperating with the Communist Party and the Soviet Union — which is what refusing to testify or taking the Fifth amounted to — would have been infinitely worse. Kazan had left the party in 1935, disgusted by its rigid authoritarianism and conspiratorial secrecy. He knew that the Communists were not just another political party; they were an arm of Stalin's foreign policy, and their purpose was to promote Soviet interests in the United States.

Already in 1935 it was becoming clear that what Soviet communism had brought about — and therefore what the American Communist Party stood for — was purge trials, mass murder, and the wholesale destruction of liberty. By the time of the HUAC hearings, the horrors of Stalinism were so patent that no one could pretend that party membership was merely a profession of idealistic concern for the downtrodden.

"After 17 years of watching the Soviet Union turn into an imperialist power," Kazan asked himself, "was that truly what I wanted here?" Up to that point he hadn't spoken out, but "wasn't what I'd been defending ... by my silence a conspiracy working for another country?"

At every turn, American Communists and fellow travelers undeviatingly toed the Soviet line. They defended the purge trials, the Hitler-Stalin pact, the Rosenbergs. Was Moscow against the Marshall Plan? They denounced it. Did Moscow oppose the US defense of South Korea? Then they opposed that too.

And by the same token, they would acclaim hardened communists like the Hollywood Ten as heroes while blackening Kazan's name as a "rat fink" and "informer."

But the truth is that Kazan was not detested for naming names. If he had identified members of the American Nazi Party, the left would have lionized him. If he had testified before a committee investigating the Klan, Hollywood would have cheered.

No: Kazan was loathed because he was anticommunist. That was his unforgivable sin. That was why he had to be showered with contempt. When he was called upon to choose sides in the great moral conflict of our time, Kazan came down against the totalitarians. For that he has been hated since 1952.

Only recant, Kazan's foes now say, and we'll call off the protest. "If he apologized," says Polonsky, the communist-sympathizing ex-screenwriter, "nothing would take place. It would be accepted that people make mistakes."

How vile these people are. Kazan apologize! It is Polonsky who should beg forgiveness — he and all the leftists who made excuses and averted their gaze as 20th-century communism drowned half the planet in misery. Human beings died by the tens of millions, and America's communists and fellow-travelers sided with the killers. They were the real betrayers. Theirs is the indelible shame. To be hated by Polonsky and his ilk is a signal achievement, one for which Kazan deserves our gratitude and applause.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.