AFTER YEARS of turmoil at the National Endowment for the Arts, Congress adopted a significant reform: It curtailed the agency's power to bestow grants on individuals. For decades such grants had been used to subsidize some of the crudest stuff ever to masquerade as art.

Examples abound. Here are three:

- The NEA repeatedly lavished money on the photographer Joel-Peter Witkin, whose images no one will ever confuse with Ansel Adams's. One of his exhibited photos shows amputated genitalia perched atop two skulls. Another depicts a scene titled "Testicle stretch with the possibility of a crushed face." Still others are too proctologically nasty to describe in a family newspaper.

- An early NEA favorite was Judy Chicago, who was generously rewarded for her sculpture "The Dinner Party." It purported to illustrate the role of women in history by means of a triangular table set for 39. The place settings consisted of vaginas on dinner plates, each commemorating a famous woman.

- Peter Orlovsky scored a $10,000 grant from the NEA for his poetry. Even the titles of some of Orlovsky's work are unprintable. The poems themselves explore such uplifting themes as ejaculating on the family cat and a mother performing oral sex on her infant son.

The elimination of most grants to individuals didn't correct the NEA's fundamental flaw, which is that government shouldn't be meddling in the arts in the first place. But it was certainly a step forward.

Now comes William Ivey, the chairman of the arts endowment, with a call to step back.

"The individual artist is at the center of what art is," Ivey told an audience at Chicago's Museum of Contemporary Art last month. "We want to get back to the business of supporting individual artists."

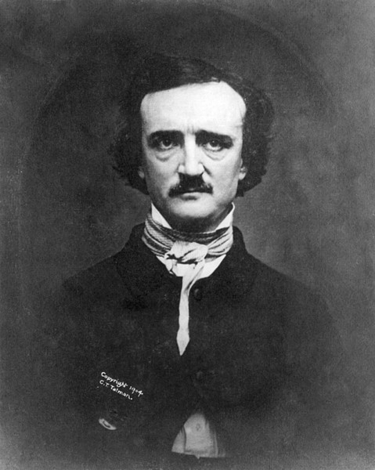

Like many great artists and writers, Edgard Allen Poe spent much of his life struggling with poverty and rejection. |

Do we? Subsidizing individual artists with tax dollars cuts deeply against the grain of a society in which all citizens are presumed equal. Hundreds of thousands of Americans call themselves artists; how can any government bureaucracy presume to choose the dozen or so who deserve a check from the Treasury? And how can any thoughtful taxpayer be confident that the bureaucrats will make the right choice?

The NEA's history of grant-making to individuals was rife with favoritism, nepotism, and logrolling.

"The writer Geoffrey Wolf, who would go on to win a $20,000 NEA fellowship in 1987," journalist Mark Lasswell reported in 1990, "served on the literature panel that awarded his brother, writer Tobias Wolff, a $20,000 grant in 1985 . . . . A young artist named Amanda Farber won a $5,000 award based on the recommendation of a panel that included her stepmother, Patricia Patterson. . . . The peer panel that recommended Karen Finley and Holly Hughes for their disputed grants included Jerry Hunt, a musician who has frequently collaborated with Finley, and Ellen Sebastian, a director who has worked with Hughes. But wait, it gets better: The panel also recommended awards to Hunt and Sebastian!"

A system in which arts insiders get to distribute government money to their friends and allies is a system begging to be corrupted. If Congress lets the NEA resume dispensing money to individuals, all the old abuses will resume as well.

Serious artists do not need government grants. The notion that artists must be protected from struggle and poverty is belied by the countless tales of painters, musicians, and writers whose talent and passion were sharpened for years against a whetstone of financial trouble.

Willem de Kooning, who immigrated to America as a stowaway on a cattle boat, labored long as a sign painter and carpenter before achieving renown for his abstract expressionist paintings. James Baldwin grew up in the poverty of a Harlem slum and wouldn't have been James Baldwin if he hadn't. The fiction and poetry of Edgar Allan Poe came from the pen of a man who had been forced out of college and disowned by his family and who suffered in a private hell of debt and alcoholism. Irving Berlin, poor son of poor parents, supported himself as a singing waiter in New York's Bowery.

It ill serves artists to liberate them from the risks and pressures of real life. No true artist was ever silenced for lack of a $10,000 handout from the NEA. By contrast, NEA handouts have encouraged scabrous pseudo-artists to keep churning out "art" that the public doesn't like and would never willingly support.

Endless young men work and work at honing their basketball skills, enduring countless hours of unrewarded practice in the hope of one day playing in the NBA. Unknown rock bands beyond number devote every spare minute to perfecting their sound and playing hole-in-the-wall gigs, driven by a love of music and the dream of a big recording contract. Who imagines that a National Endowment for Basketball is required to sustain the quality of hoops in this country? Who believes that without a National Endowment for Rock 'n' Roll, struggling rockers would give up in despair?

Artists — real artists — are no different. It isn't the government for whom they write and paint and dance. The state is not the mainstay of their art. The public is — their public, the patrons and donors and audiences who are drawn to their work and support it willingly. We wouldn't dream of letting the government pass judgment on rock and roll or basketball. Is art any less sacred?

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.