William Henry Harrison was the ninth US president. |

Two presidential candidates face off in a rematch. One candidate, his affluent background notwithstanding, is seen as a populist; his supporters hail him as the champion of ordinary people and deride the incumbent as a pampered creature of the establishment. He's also the oldest person ever to run for president, and even his backers worry that he is not up to the demands of the job. All the while, the nation's problems are growing more serious. But the electorate is so polarized that all the two parties seem to agree on is how much they detest each other.

Welcome to the campaign of 1840.

President's Day arrives this year amid the overwhelming likelihood that Joe Biden and Donald Trump will once again be the Democratic and Republican nominees for president. Never have two men so old competed for the White House. And never, millions of Americans would say, have presidential politics been so cynical and shallow.

The history of William Henry Harrison can offer some perspective.

The nation's ninth president is largely forgotten today. Many voters know nothing about Harrison except that he caught pneumonia after his inauguration and died within a month.

But if there's not much to say about Harrison's presidency, the campaign that made him president is a very different story — one that still reverberates in 2024.

He was born in Virginia to a wealthy family; his father was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. After trying his hand at studying medicine, Harrison commenced a military career that took him to the western frontier. He saw action during the Northwest Indian War and then spent 12 years as governor of the Indiana Territory. His reputation grew as he clashed with the confederation of the Shawnee leader, Tecumseh. At the inconclusive Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, Harrison repelled a surprise Indian attack and emerged as something of a war hero — "Old Tippecanoe" — notwithstanding the heavy losses his troops had sustained. Promoted to general in the War of 1812, Harrison led US forces in the more significant Battle of the Thames in Ontario, inflicting a major defeat on the British and their Indian allies.

The next quarter century Harrison spent in politics. As a congressman and senator from Ohio, he followed Henry Clay and joined the new Whig Party organized by Clay to oppose President Andrew Jackson's Democrats. In 1836, the Whigs — unable to unite behind a single presidential ticket — ran four regional candidates instead. One of them, Harrison, drew considerably more votes than the other three combined. That wasn't enough to defeat Vice President Martin Van Buren, who succeeded Jackson and become the nation's eighth president. But it was enough to position Harrison for another run in 1840, when he became the Whigs' nominee. What ensued was a campaign for president unlike anything American politics had known before.

To begin with, Harrison campaigned openly and vigorously, defying the expectation that presidential candidates would steer clear of the political hurly-burly while their surrogates traveled on their behalf. While Van Buren maintained the traditional aloofness, Harrison hit the hustings, eager to neutralize the president's huge advantage in name recognition and enable voters to see for themselves the military hero from the West. Democrats were outraged by this breach of custom. "Was there ever before such a spectacle . . . as a candidate for the presidency, traversing the country, advocating his own claims for that high and responsible station?" huffed the Cleveland Advertiser, a pro-Van Buren paper.

Taking a leaf from the old Jacksonian playbook, the Whigs portrayed Harrison as the "people's candidate," a man of humble origins and frontier values. They mocked Van Buren as a fop who lived high on the hog and had turned the White House into a palace "as splendid as that of the Caesars." The truth was the reverse — Harrison had been raised on a Virginia plantation, while Van Buren was a tavernkeeper's son who grew up among Dutch immigrants — but the Whigs maligned Van Buren so skillfully that his reputation never recovered.

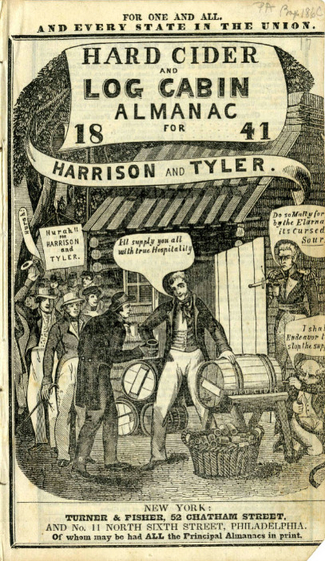

Naturally, the Democrats did their best to malign Harrison. One line of attack was to portray him as a hick with a taste for booze. "Give him a barrel of hard cider and a pension," a Democratic paper in Baltimore sneered, and he would spend "the remainder of his days in a log cabin," lolling before the fireplace. The jibe backfired spectacularly. Whigs adopted the "log cabin and hard cider" image as a badge of honor, further proof that Old Tippecanoe was a heroic, down-to-earth man of the people. Before long, "Log Cabin and Hard Cider" references were everywhere. Whig rallies and parades featured rolling log cabins built for the occasion, and copious quantities of hard cider were dispensed to thirsty voters.

The "log cabin and hard cider" image began as a jibe against Harrison by Democrats, but the Whigs adopted it as a badge of honor, proof that Old Tippecanoe was a down-to-earth man of the people. |

Log cabin imagery became so powerful, wrote Gail Collins in her biography of Harrison, "that it became almost imperative for every Whig politician to find a log cabin in his history." The fact that Harrison had neither been born in a log cabin nor lived in one as an adult — indeed, he had built himself an elegant brick mansion as Indiana's territorial governor — made no difference. Nor did the fact that Harrison was not a hard drinker and frowned on those who were. Reality was overpowered by campaign symbolism and sloganeering, setting a pattern for scores of presidential campaigns to come.

Democrats had better success with a different line of attack. Harrison was 67 years old in 1840, making him by far the oldest candidate for president to that time. As the historian Paul Boller has recounted, Democrats taunted the Whig nominee as "Granny Harrison." They "called him senile, said he was both mentally and physically failing, [and] ridiculed his . . . at times incoherent way of expressing himself."

But the concerns about Harrison's age were legitimate. Whigs publicly dismissed the issue, though in private many worried. "If Genl. Harrison lives, he will be President," Daniel Webster, the influential Massachusetts senator, wrote uneasily to a confidant. The unease didn't dissipate after Election Day. "Harrison comes in upon a hurricane," remarked former president John Quincy Adams. "God grant he may not go out upon a wreck."

By Inauguration Day, Harrison had turned 68. The weather on March 4, 1841, was raw and windy, but the president-elect, to show his undiminished vigor, insisted on taking the oath without hat or overcoat. Then, still unprotected from the elements, he delivered an inaugural address that lasted almost two hours — the longest in US history. The ordeal left him weakened; he took ill a few weeks later, rapidly developed pneumonia, and died on April 4.

The legacy of the first Whig president echoes to this day, when even presidential hopefuls worth great fortunes and long accustomed to power strain to be seen as one of the people. In 1840 the candidates invoked log cabins and hard cider; in 2024, they boast of growing up in working-class Scranton or conspicuously don baseball caps while campaigning.

But the Harrison campaign is also a reminder that mortality can play a grim role in presidential politics. Harrison was the first president to die in office of natural causes. The same fate would later befall Zachary Taylor, Warren Harding, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Voters in 2024 might bear that history in mind as the two major parties prepare to nominate the oldest candidates ever. The presidency was no job for an old man in 1840. It is even less so today, when the job is vastly more demanding — and the leading candidates are far older than was Old Tippecanoe.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.