After the 1910 census, the number of US representatives was raised to 435. It has remained frozen at that size ever since. |

THE SUPREME COURT last month settled the issue of whether, for purposes of apportioning seats in Congress, the Census may rely on statistical sampling in addition to the traditional head count. (It may not.) But the court has never addressed the far graver issue of whether Americans can in any meaningful way be represented by a body as small as the House of Representatives.

A few numbers:

Between 1950 and 1990, the population of Illinois climbed by 31 percent, from 8.7 million to 11.4 million. Ohio's population grew from 7.9 million to 10.8 million, a 37 percent increase. And the number of Massachusetts residents rose 28 percent, from 4.7 million to 6 million.

Yet over the same period, each of these states (along with 20 others) lost seats in Congress. Illinois sent 25 representatives to Washington in the 1950s; it sends 20 today. Ohio's House delegation shrank from 23 to 19. The number of Massachusetts congressmen dropped from 14 to 10.

For states that gain voters to lose seats in the "people's house" is surely an affront to democracy. But it is unavoidable so long as the number of representatives remains fixed at 435. When the House is reapportioned after each decennial Census, only those states whose populations have grown the most are awarded new seats. Since reapportionment is a zero-sum game, for every state that gains a member, another state must lose one.

But what is sacrosanct about the number 435? It is not required by the Constitution. On the contrary: The Framers envisioned a House of Representatives that would keep growing as the nation grew.

"I take for granted," James Madison wrote in The Federalist, "that the number of representatives will be augmented from time to time." The Constitution specified that the first House of Representives would comprise 65 members, one for every 30,000 Americans. To Anti-Federalist complaints that 65 was too low a number to make the House truly representative, Madison replied: "The foresight of the [Constitutional] Convention has . . . taken care that the progress of population may be accompanied with a proper increase of the representative branch of the government."

And to drive the point home, he noted that one reason for conducting a Census every 10 years was to "to augment the the number of representatives at the same periods."

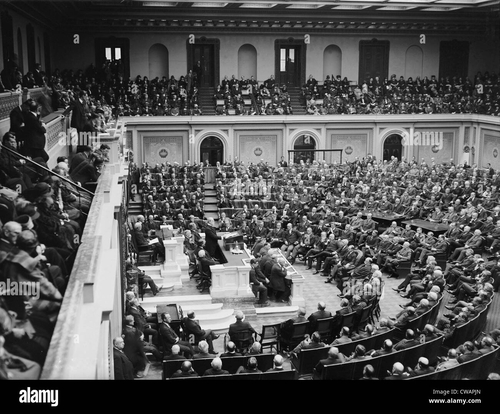

For 130 years, the system worked as the Framers intended. After every Census, Congress routinely enlarged the House. From 65 seats in 1789, the House swelled to 105 after the 1790 Census, 141 after the 1800 Census, 181 after the 1810 Census, and so on.

But the last time the House grew was after the 1910 census, which counted 92 million people. The number of representatives was raised to 435 — and there it has stood ever since. When the 1920 Census confirmed that a tidal wave of immigrants was surging into the nation's cities, anti-immigrant and rural forces in Congress balked at creating new districts to accommodate them. This didn't mean that the newcomers went unrepresented. It simply meant that existing congressional districts grew more crowded.

Which is how we got to where we are today, when the average district contains 600,000 persons. It is an iron law of politics that the more constituents an elected official is answerable to, the less he is answerable to anybody. When the House of Representatives first convened, every 30,000 Americans had their own voice in Congress. Today they share that voice with 570,000 others. What was meant to be the government's most democratic body has lost 95 percent of its representativeness.

By global standards, 600,000 residents per district is absurdly high. No industrialized nation in the world elects members to its lower parliamentary chamber from districts so congested. Many countries with much smaller populations than ours have bigger legislatures. The Russian Duma has 450 members; the lower house of the Japanese Diet, 500; the French Assemblee, 577; the German Bundestag, 656. Great Britain's population is less than one-fourth that of the United States, but its House of Commons, with 659 members, is half again as large as the US House.

Voters hold Congress in disdain because they sense that its members are out of touch, more concerned with their political careers than with the wishes of their constituents. A return to the principle that growth in population requires growth in representation could change that. Enlarge the House to 1,200, and the ratio of members to residents would be about 1:215,000, roughly where it was in 1910. Still far from the Framers' ideal of 1:30,000 — but a long way toward making Congress more representative.

And the benefits! Districts would be smaller and more compact, more closely aligned with discrete communities and neighborhoods. Because campaigns would cost less, PACs and lobbyists would recede in importance. Because it would take fewer votes to win an election, the House would be likelier to reflect America's social diversity. Elections would be more competitive. Voters would pay more attention.

Best of all, representatives would be closer — and more accountable — to those who elect them. We have drifted pretty far from the core value of the American experience, that government should answer to the people. A bigger House can help take us back.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.