(First of two columns)

We came up with certain solutions, and — damn, it was working quite well, really.

— Federal Judge Arthur Garrity Jr., author of Boston's racial busing plan, in a recent interview

HE WOULD WIN, hands down, any contest for the Most Hated Bostonian of the last 30 years. And deservedly so. For Judge Garrity did more than inflict on Boston's schools and families a nightmare of riots, fear, racial hatred, and civic trauma. He did it with such blithe indifference to the pain of those he was hurting, such cool disdain for anyone who doubted the wisdom of accomplishing integration through massive crosstown busing, that to this day he still insists, "Damn, it was working quite well, really."

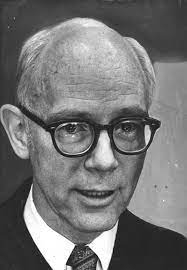

U.S. District Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. |

This June will mark the 25th anniversary of Garrity's order to forcibly achieve racial balance in Boston's public schools, an order that convulsed the city and triggered the most violent and notorious antibusing backlash in the nation. Images from the riots of 1974 still sear. Stanley Forman won the Pulitzer Prize with his unforgettable photograph of a black man being rammed with an American flag outside Boston City Hall.

"The plan that Garrity imposed upon the city was punitive in the extreme," write Stephan and Abigail Thernstrom in "America in Black and White," their essential 1997 book on race relations. "Indeed, the judge's advisers and the state Board of Education believed that those against whom it was directed — in their eyes, localist, uneducated, and bigoted — deserved to be punished. The plan thus paired Roxbury High, in the heart of the ghetto, with South Boston High, in the toughest, most insular, working-class section of the city. Black students bused in from Roxbury would make up half of the sophomore class at South Boston High, while the whole junior class from 'Southie' would be shipped off to Roxbury High."

It seems incredible that Garrity could have believed that such cruelty would be good for either Boston's schools or its race relations. But he was a megalomaniac, intoxicated with his own power and blinded by self-importance. A quarter-century later, he still finds nothing to reproach himself for. "Looking back to the circumstances confronting me at the time," Garrity told The Boston Globe in a recent interview, "I would not have done things any differently."

He finally relinquished control of the schools in September 1985, after more than 11 years of excruciating rule. In a fine retrospective on the busing tragedy, Matthew Richer notes in the November/December issue of Policy Review that Garrity "micromanaged everything from student transfers to ordering the purchase of 12 MacGregor basketballs. . . . [He] meddled in every aspect of the Boston public schools. He placed South Boston High into federal receivership and fired its popular principal. He decreed rigid racial quotas in faculty and administrative hiring. When one elementary school was converted to a middle school, Garrity issued an order requiring the urinals to be raised."

All the while, the most hated man in Boston wasn't even a Bostonian. Throughout his dominion over the city's public schools, Garrity lived in the posh suburb of Wellesley, a universe away from the people and neighborhoods his orders so brutally affected. Richer recounts the futility with which Mayor Kevin White tried to get Garrity to dispatch US marshals to help stop the violence that was ripping Boston apart.

"Garrity dismissed the mayor's plea," Richer records, "and insisted that 'integration in the schools can be achieved by community efforts.' The judge was apparently less confident in community efforts to safeguard his own home in Wellesley, however, stationing two deputy federal marshals there around the clock."

In Boston as in every other city where it was imposed, forced busing was hugely unpopular. Whites overwhelmingly opposed it; within a few years, so did the vast majority of blacks. In 1982, a Boston Globe poll showed that busing — or "court-ordered student assignment," as it was euphemized — had the support of only 14 percent of black parents with children in the public schools. What parents of every color wanted was control over their children's education. They wanted their kids to go to school near their homes. They wanted to be heard; they wanted their views views to count for something.

"I remember when we first started deseg," one Boston principal recalled in 1991, "and a black lady came to look at the school and said, 'You have a beautiful school here. But if my child ever learns to hate a white person, it's going to be from coming to your school on a bus — because we don't want to do it.' She had a child in the first grade, and she wanted the kid to go to a school that she could see."

Most parents had no objection to integration. But they objected bitterly to having their kids shoved around by liberal social experimenters from the suburbs. Why should that have been so hard for Garrity to comprehend?

Busing was doomed to failure from the outset. It made everything worse — race relations, public education, the neighborhoods, Boston politics. Everyone sees that now. Everyone except Garrity, who maintains, arrogant as ever, that he was right and all the critics were wrong. "Damn, it was working quite well, really."

NEXT: Busing's aftereffects

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.