ANY BOOK on Jewish statesmanship must contend with the fact that for most of the last two millennia, Jews had no state. Jewish sovereignty in the Holy Land came to a cataclysmic end in 70 CE, when the Roman legions under Titus destroyed Jerusalem and burned its great temple. Not until 1948, with the proclamation of the new State of Israel, would Jewish statehood be revived in the Jewish homeland.

In Providence and Power: Ten Portraits in Jewish Statesmanship, Rabbi Meir Y. Soloveichik sets out to fill a gap in the vast literature of political leadership — the lack, in his words, of any studies focused on "the particular nature of Jewish statecraft" or devoted to "outstanding exemplars of that calling." To remedy that deficiency, he profiles an array of leaders drawn from the long history of the Jewish people, from the biblical King David in the 10th century BCE to David Ben Gurion and Menachem Begin 3,000 years later.

David, the quintessential Jewish monarch, reigned in Jerusalem during the First Jewish Commonwealth. Ben Gurion and Begin, the most important prime ministers in the history of modern Israel, likewise governed a sovereign Jewish state. But just one other leader included by Soloveichik was a Jewish ruler in a Jewish land: the Second Temple-era Queen Shlomtsion (also known as Salome Alexandra), who became monarch of Judea a century before the Roman conquest.

Within the context of Providence and Power, those four are the exceptions to the rule. All the book's other subjects — among them the Sephardi sage and courtier Don Isaac Abravanel; the eminent 17th-century Amsterdam rabbi Menasseh ben Israel; and Theodor Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism — were individuals who lived after Jewish national independence was crushed and before it was reborn. They represented no Jewish government; they were not diplomats or foreign ministers answerable to a Jewish principal; they were not backed by the authority of any Jewish army, parliament, or regime. So isn't it something of a stretch to hold them out as archetypes of Jewish statesmanship?

Not at all, argues Soloveichik.

"Statecraft is, at its essence, the marshaling and application of available power on behalf of one's people," he writes,

and also, in the Jewish case, the representation of one's people before the powerful. During those stateless millennia, it was often precisely the challenges of life in dispersion and subjugation that gave rise to some of the most compelling embodiments of Jewish statesmanship on the part of figures who refused to give up on the Jews as a people and who acted in the political realm to safeguard their posterity.

In short, statesmanship is possible even in the absence of statehood or state power. The men and women highlighted by Soloveichik lived in different lands and centuries, but they were linked by what he calls "the fixed lodestar of their own Jewish identity and the high compelling duty of service to the well-being of the Jewish people."

* * *

SOLOVEICHIK IS of course well known to readers of Commentary, for which he has written a monthly column since 2017. He is renowned in the Jewish world for his intellectual agility, his brilliance as a writer and speaker, and his prolific output. In 2013 he became the rabbi of Congregation Shearith Israel, the oldest synagogue in the United States (the shul's website identifies him as "our tenth minister since the American Revolution"). He is also the director of the Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought at Yeshiva University and the creator of the remarkable daily podcasts, Bible 365 (a book-by-book examination of the entire Hebrew Bible) and Jerusalem 365 (a survey of the holy city's 4,000-year history).

The overarching theme of Providence and Power is the defense of Jewish national identity. Over the millennia, that defense took vastly different forms. For Esther, the secret Jew who became queen in the Persian court, it meant crafting a strategy to thwart a planned antisemitic genocide. For Louis Brandeis, a committed assimilationist, it meant becoming an outspoken champion of Zionism and then, at a delicate moment, assuring Britain's foreign minister of crucial behind-the-scenes American support for issuing the Balfour Declaration. For Benjamin Disraeli — the book's only non-Jewish "Jewish" statesman — it meant an unprecedented speech in the House of Commons, in which he advocated for the right of Jews to enter Parliament by invoking the debt Christianity owed to Judaism.

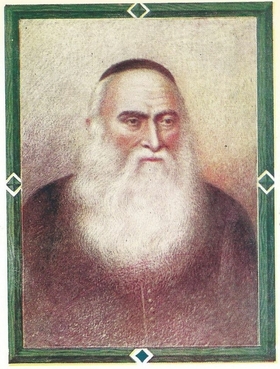

And for Abravanel, who to my mind is the most tragic and haunting figure in the book, defending the Jewish people meant relinquishing all his personal prestige, wealth, and power — not once, but twice. A towering Torah scholar and financier who rose to the heights of influence in Portuguese society, he lost everything in 1483 when he was forced to flee by the accession of a hostile new king. Incredibly, Abravanel rebuilt his career in neighboring Spain, becoming a trusted adviser and banker in the court of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella — only to lose it all again in 1492, when the royal couple ordered the expulsion of every Jew from their kingdom. Many prominent Spanish Jews retained their holdings by converting to Christianity, and the king and queen offered Abravanel fantastic honors and inducements if he would do likewise. Not only did he refuse, he had the audacity to tell them that what they were doing was futile — that the Jewish people and their faith were eternal, and not even the Catholic Monarchs of Spain could destroy them.

Typically statesmen are remembered for what they do. "But sometimes," Soloveichik comments,

what they refuse to do can more truly define their legacy. Isaac Abravanel, with the eyes of Spanish Jewry upon him, with his fellow pleaders at court prepared to forswear their identity, with the most powerful monarchs in the world inviting him to take his place beside them and reap the rewards, gave up everything for his faith.

Ultimately Abravanel left Spain with tens of thousands of other Jews, having failed in his desperate efforts get the order of expulsion revoked. But it is in his defiant defense of the Jewish faith that Soloveichik sees true statesmanship. He quotes the conclusion of Benzion Netanyahu, the great historian of the Spanish Inquisition (and father of the current Israeli prime minister): "Abravanel lost the political battle . . . but [he] also fought for his people's soul, and in this struggle he won a complete victory."

* * *

PROVIDENCE AND POWER originated as a series of lectures delivered for the Tikvah Fund. The book reflects the strengths of that format, at which Soloveichik excels.

Don Isaac Abravanel, a towering scholar and financier in the 15th century, was offered fantastic inducements by the monarchs of Spain to convert to Christianity. When he refused, he was expelled with tens of thousands of his fellow Jews. |

The very different Jewish leaders he portrays come alive in his accounts, as he mixes poignant details of human interest into compelling descriptions of the environment in which each individual lived and worked. The author's erudition is immense, but he deploys it lightly and to the point. As in a good lecture, each portrait in the book is replete with memorable sketches, surprising asides, interesting quotations, and a clear conclusion. In his chapter on King David, for example, Soloveichik comfortably disputes Isaiah Berlin's famous hedgehog-and-fox analogy, quotes Natan Sharansky's memoir of life in the Gulag, discusses the famous 1967 photograph of Israeli paratroopers at the Western Wall, adduces Winston Churchill's biographer on the subject of Churchill's towering ego, and cites multiple passages from the books of Samuel and Psalms. And he does it all without losing track of his central point, namely David's awareness of God's presence as a constant throughout his career.

To be clear, this is an informal, anecdotal volume. It is not meant to be a systematic or scholarly analysis of statesmanship. Though Soloveichik ends his book by drawing out several themes common to the lives of the men and women he recounts, his foremost purpose is plainly to tell their stories, placing them in the sweep of the larger, timeless narrative of the Jewish people themselves. Such a book would be valuable at any time; it is especially so today, when the Jewish world is rocked by intense acrimony and ill will, and when the phrase "Jewish statesmanship" seems almost mockingly ironic.

In Providence and Power, one of the great communicators of modern American Jewry has taken it upon himself to show how the Jewish past, even during the long centuries of statelessness, was illuminated by paragons of statecraft and vision. We can only pray that men and women of their caliber will emerge to shape the Jewish present and future as well.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.