The terrible Vermont floods — of 1927

Massive flooding engulfed Vermont last week when up to 9 inches of rain fell on some parts of the state. What is being called a once-in-a-hundred-years storm has caused tens of millions of dollars in damage across the state. On Wednesday it claimed a human life when 63-year-old Stephen Davoll of Barre drowned in his home.

By definition, a once-in-a-century storm — meaning a weather event with, on average, a 1 percent chance of occurring in any given year — can be expected to occur roughly once every hundred years. The fact that Vermont's flooding occurred at a time when many are intensely concerned about climate change doesn't mean the storm was caused by global warming, but of course that is the most popular interpretation.

In truth, as the Vermont Historical Society notes, Vermont has a long record of floods, with more than 20 major inundations in the past 200 years. Catastrophic as recent events have been, the most devastating flooding in Vermont's history happened in November 1927 and is regarded as the worst natural disaster in the annals of the

Green Mountain State. The death toll was 84, unimaginable by today's standards. Among those killed was the state's lieutenant governor, who was swept away when he tried to leave his car and wade through the rising water.

"In Bolton, 19 [residents] in one boarding house drowned when the Bolton Valley Dam broke," the historical society records. "The loss to 23 manufacturing plants was $2,812,500. In Montpelier, where only two stores carried flood insurance, the staggering loss totaled an average of $400 for every man, woman, and child in town. . . . Total damage in the state resulting from the flood was estimated at $35 million." In 2023 dollars, that is the equivalent of $613 million.

In the 1927 flooding, 9,000 people — 1 out of every 39 Vermonters — were left homeless. The storms wreaked havoc on the state's infrastructure. More than 1,250 bridges were washed away or severely damaged. In this month's flooding, by contrast, only two bridges were destroyed.

Pedestrians navigated floodwaters outside City Hall in downtown Montpelier, Vt., July 10, 2023 |

The president at the time of the 1927 calamity was the popular Calvin Coolidge, a Vermont native. Today, vast amounts of federal funds are routinely and promptly funneled to states coping with natural disasters, but Coolidge resisted such intervention on principle, believing that relief and recovery should primarily be undertaken by the states themselves, bolstered by charitable giving. Many Vermonters shared that view, including Governor John Weeks. When US Army Capt. Charles Ferrin offered to put the military at the state's disposal, Weeks reportedly replied: "Captain, Vermont can take care of its own."

Vermont did take care of its own. As historian Amity Shlaes recounts, "individual Vermonters, companies, charities, and the state government did much to help themselves and the citizens." The Legislature approved spending $8.5 million for repairs — a sum equal to half the state's annual budget (and the equivalent of $150 million in today's money). The Red Cross channeled $1 million in charitable donations to Vermont. Ultimately the federal government did contribute more than $2 million to underwrite highway reconstruction.

Whatever the link between climate change and this month's Vermont flooding, one point stands out: The number of people dying because of extreme weather events in our time is a tiny fraction of those who lost their lives a century ago. In the 1920s, the world averaged over 500,000 deaths from natural disasters per year. Since 2010, despite a quadrupling of global population, the annual number of deaths from such disasters has fallen to well below 50,000 — a decrease of more than 90 percent. Why? Because societies are wealthier, their technology is vastly improved, and their infrastructure is far more advanced than was the case 100 years ago. Fossil fuels and rising CO2 levels may have a negative impact on the planet's climate. But industrialization has had an enormously positive impact on the ability of human beings to protect themselves from climate-related killers.

Ten months after the terrible flooding of 1927, with just six months left to his presidency, Coolidge and his wife, Grace, paid a visit to the state of his birth. After two days of traveling across Vermont to inspect recovery efforts, their train reached Bennington, where 5,000 residents waited to see the First Couple. There were cries of "Speech, speech!" but reporters had been told that there would be no speeches during the president's trip, so no one expected him to say anything noteworthy.

Yet as Coolidge stood on the train's rear platform, he was moved to say a few words. What he uttered, wholly extemporaneously, was a heartfelt paean.

After a few sentences describing where he had been and what he had seen over the previous two days, Coolidge reflected on his feelings for the state:

"Vermont is a state I love," the president told his audience.

I could not look upon the peaks of Ascutney, Killington, Mansfield, and Equinox without being moved in a way that no other scene could move me.

It was here that I first saw the light of day; here that I received my bride. Here my dead lie buried, pillowed among the everlasting hills. I love Vermont because of her hills and valleys, her scenery and invigorating climate, but most of all, I love her because of her indomitable people. They are a race of pioneers who almost impoverished themselves for the love of others.

"If ever the spirit of liberty should vanish from the rest of the Union, it could be restored by the generous store held by the people in this brave little state of Vermont."

The spirit of that brave little state endures. Vermont recovered from the floods of 1927. It will recover, stronger and more resilient than ever, from the floods of 2023.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

John Kerry hasn't changed

I have never been a John Kerry fan, to put it mildly. His politics have always been at odds with mine, but that's not the reason for my aversion. I have taken to print any number of times to express admiration or appreciation for people with whom I have strong political differences. But Kerry's smug self-righteousness, along with his willingness to subordinate any larger principle to his own personal or political gain, has always repelled me.

That irritating smugness was on display on Capitol Hill Thursday when Kerry, the former Massachusetts senator and secretary of state who is currently President Biden's special presidential envoy for climate, testified before the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Oversight and Accountability.

When one committee member, Representative Cory Mills of Florida, made a smart-alecky passing reference to Kerry's use of private jets, the witness lashed out.

"I just don't agree with your facts, which began with the presentation of one of the most outrageously persistent lies that I hear, which is this private jet," Kerry said.

We don't own a private jet. I don't own a private jet. I personally have never owned a private jet. And obviously it's pretty stupid to talk about coming in a private jet from the State Department up here.

Someone who didn't know better might have assumed that Kerry was bristling with indignation because he had been falsely accused. But Representative Michael Waltz, another Florida Republican (and, incidentally, the first Green Beret to serve in Congress), did know better and decided not to let Kerry get away with it. The exchange that followed was illuminating.

Waltz: "You just testified, under oath, that you never owned a private jet. I'd like to enter into the record an article from Feb. 15, 2023 — 'John Kerry family private jet sold shortly after accusations of climate hypocrisy.' Mr. Secretary, do you stand by your testimony that you have never owned —"

Kerry: "I personally — yes, my wife owned a plane."

Waltz: "You flew on that plane?"

Kerry: "Not in a number of years, but I have flown on it, sure."

Waltz: "This article, then, was not inaccurate. Your family owned a plane, you flew on the plane —"

Kerry: "My wife owned the plane."

Waltz: "Here's the issue. This isn't some kind of partisan 'gotcha.' When we are asking Americans to make serious sacrifices as we transition for the common good, and your family or yourself are flying around on private jets, that smacks of hypocrisy and actually hurts your cause."

A little later in the exchange, Kerry insisted that he only flies commercially. So Waltz asked him point-blank: "Have you flown a private jet in a personal or official capacity since you've taken this position?" Kerry replied: "Possibly once — I don't — I think — I just don't — I'm trying to think."

Waltz's point was clear to everyone. But Kerry pretended not to understand, so the congressman gave it one last shot.

"I think you need to take the broader point of how this appears to the American people," he said. Unable to stop digging the hole, Kerry responded with a non sequitur: "We're not asking Americans not to fly!"

Kerry could have avoided the entire exchange. Instead of fuming about "outrageously persistent lies" when Mills needled him about flying in a private plane, Kerry could have graciously acknowledged the point. "You know," he might have said, "it's true that I used to fly on a private family jet. But I sold it months ago, in order to reduce carbon emissions when I travel."

It's a strange thing about Kerry. As a Swift Boat commander in Vietnam, he was courageous and resolute. But never in his long political career has he shown comparable steadfastness. His hallmark has been a willingness to trim with every shifting breeze, while haughtily dismissing anyone with the temerity to challenge or contradict him.

Examples of that hauteur abound. A notable one is Kerry's adamant insistence at a prestigious forum in 2016 that no Arab nation would ever make peace with Israel until the conflict with the Palestinians was settled.

"There will be no separate peace between Israel and the Arab world. I want to make that very clear to all of you," admonished Kerry, who was then secretary of state. "I've heard several prominent politicians in Israel sometimes saying, well, the Arab world's in a different place now, and we just have to reach out to them and we can work some things with the Arab world, and we'll deal with the Palestinians. No. No, no and no. . . . Everybody needs to understand that. That is a hard reality."

Of course, Kerry was dead wrong. Just a few years after he left office, the Abraham Accords established peace between Israel and (so far) four Arab countries: Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Morocco, and Sudan. Has Kerry ever acknowledged that he completely misread the situation? Has he ever acknowledged that his judgment on anything was completely off base? I cannot recall any instance. But if his capacity for humbleness is microscopic, his depths of self-regard are vast.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, a few months ago, Kerry sang the praises of himself and his fellow jet-setters, marveling at how "extraordinary" it was that people like them — "a select group of human beings" — had flown to the Alpine resort to "sit in a room and come together and actually talk about saving the planet." Why, he said, "it's so, almost extraterrestrial, to think about saving the planet."

I have been following Kerry's political career since he was in his 30s. Now he is approaching 80, but he remains the same self-adoring, sanctimonious showboat that "Doonesbury" was skewering as far back as 1971. With decades in public life, some people grow into wise statesmen, perceptive sages, venerated role models. John Kerry merely grew old.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

One giant leap for mankind

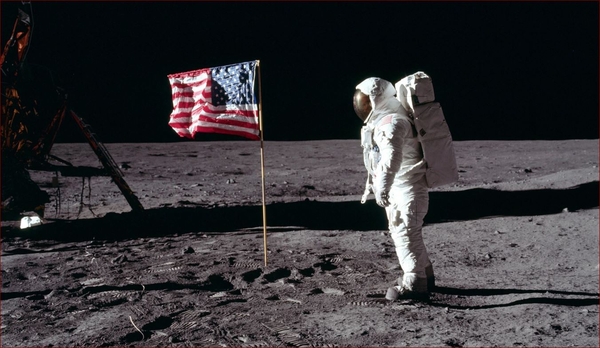

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon, facing an American flag and the Eagle lunar lander. |

I was born late in the Baby Boom and have seen innumerable technological miracles become routine — personal computers, soft contact lenses, digital cameras, GPS, heart transplants, you name it.

But to my mind, no innovation or scientific achievement will ever outdo the one that entranced me and several billion of my fellow human beings 54 years ago this week, when three Americans lifted off from Earth in a Saturn V rocket and flew to the Moon. I doubt I am the only person who regards the first landing on the Moon as the acme of human achievement — an accomplishment so extraordinary, so fabulous, so surreal, that it still stands alone: the watershed moment of the last millennium.

The Apollo 11 mission has been memorialized in an endless catalog of books, documentaries, oral histories, and recordings. (If you'd like my recommendation, the definitive history — magisterial, riveting, and intimate — is Andrew Chaikin's spectacular 1994 volume, "A Man on the Moon.") But there is magic as well in just looking at pictures of the mission and reliving something of the wonderment of those days. On its website, National Review has posted a gallery, drawn from the NASA archives, that contains dozens of images of that first moon landing, when men from the planet Earth "came in peace for all mankind" and history turned on its hinge.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "Kennedy's destructive hate-crimes bill," July 20, 1998:

The blood of bias-crime victims is no redder than that of "ordinary" victims. The daughter of a man murdered because he was black sheds tears just as hot as the daughter of a man murdered because he had $20 in his pocket. By singling out hate crimes for special statistical and prosecutorial attention, lawmakers in effect declare some victims — and some victims' grieving loved ones — more equal than others.

In an age when Americans are under constant pressure to splinter into groups — to see themselves first and foremost as members of an aggrieved race, class, or gender — the last thing they need are more laws emphasizing their differences.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"There have been tyrants and murderers and for a time they can seem invincible, but in the end they always fall. Think of it. Always." — Ben Kingsley (as Mahatma Gandhi) in Gandhi (1982)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.