Bashing the Supreme Court is an American tradition

"This is not a normal court," President Biden told reporters at the White House following the Supreme Court's decision that race-based affirmative action in college admissions is unconstitutional.

As criticisms go, that was quite measured, especially after the torrent of condemnation poured on the court after last year's abortion decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization. Critics then were tripping over themselves in their rush to declare that the high court had lost all legitimacy and no longer merited the respect or obedience of American citizens.

The justices "have burned whatever legitimacy they may still have had," seethed Senator Elizabeth Warren in a typical example of the 2022 outrage. "They just took the last of it and set a torch to it."

Everywhere on the left, there were similar denunciations. Senator Ed Markey railed against "the illegitimate, far-right majority on the Supreme Court," Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez diagnosed "a crisis of legitimacy," and the head of the Democratic National Committee scorned "this illegitimate Supreme Court". The progressive journal Current Affairs proclaimed in a headline: "The Supreme Court Has Destroyed Its Legitimacy and There Is No Reason to Respect It." In The Grio, journalist/activist David Love called for abolishing the high court: "Now is the time to shut the whole thing down and start from scratch before more people die." The Jacobin, a socialist magazine, was only slightly less apocalyptic: "For too long, progressives have accepted without question the legitimacy of the courts," it thundered. "That needs to change now."

But the Supreme Court doesn't become "illegitimate" just because it issues a decision a lot of people detest. US history abounds with rulings that provoked rage, shock, and calls for massive resistance. From Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857 to Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 to Roe v. Wade in 1973 to Bush v Gore in 2000, the high court has often sent critics into paroxysms of wrath. Perhaps no SCOTUS ruling was ever more widely loathed than Engel v. Vitale, the 1962 case in which the justices forbade government-sponsored prayer in public schools. Polls at the time found that 8 out of 10 Americans disapproved of the ruling. According to one scholar, "Engel provoked more outrage, more congressional attempts to overturn it, and more attacks on the justices than perhaps any other decision in Supreme Court history."

With Supreme Court justices sitting in the audience, President Barack Obama denounced the Citizens United decision during his 2010 State of the Union address. |

Yet in each of those cases, the court's decision was treated as binding. Just as Dobbs, once the tumult and the shouting died, was accepted as the law of the land. And just as the latest controversial rulings on racial preferences, same-sex wedding websites, and student debt cancellation will be accepted. Like most institutions in our strident era, the Supreme Court's reputation has taken a hit. But if the measure of judicial legitimacy is that rulings are obeyed, then the court's legitimacy is intact.

"Not a normal court"? That is hardly the worst thing presidents have said when justices ruled in ways they didn't like.

In 1801, President Thomas Jefferson condemned the "fraudulent use of the Constitution" that had filled the courts with "useless judges" who were using the judiciary as a base from which "all the works of republicanism are to be beaten down and erased." Three years later, he would go further, urging his allies in the House of Representatives to impeach Justice Samuel Chase a staunch Federalist, on the grounds of political bias. (Chase was impeached, but the Senate refused to convict.)

In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was so incensed by Supreme Court rulings invalidating several New Deal measures that he famously tried to "pack" the court — i.e., to create additional seats in the hope of filling them with justices more to his liking. In one "fireside chat," he said Congress had to act "to save the Constitution from the court and the court from itself" and demanded "a Supreme Court which will do justice under the Constitution — not over it." Ultimately, FDR's court-packing scheme went nowhere.

Harsh, too, was President Barack Obama's attack on the justices to their faces during his 2010 State of the Union address. Vilifying the court's decision in Citizens United v. FEC, which upheld the right of corporations and unions to spend money on political campaigns, Obama accused the justices of having "open[ed] the floodgates for special interests" and allowing elections to be "bankrolled by America's most powerful interests, or worse, by foreign entities."

I say, have at it. Presidents should feel as free to excoriate Supreme Court justices as they do to upbraid lawmakers, and members of Congress who feel like slamming the court as "illegitimate" when a ruling doesn't go the way they want should go right ahead and do so. Let legislators say what they wish about judicial decisions. Ideally, of course, they should express themselves with dignity and care, but they're politicians, so expect intemperate hyperbole from most of them.

What matters in the end is that the court's decisions are adhered to and the constitutional order respected. The executive, legislative, and judicial branches are co-equal in our system, and need not see eye-to-eye. To be a "government of laws and not of men" requires that when the court says what the law is, the nation complies. But it also means that the men (and women) who want that law changed have every right to say so, as vigorously and sharply as they like.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

How the 'millionaire's tax' helped turn a Celtic into a Maverick

For years the progressive activists at the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center advocated for passage of a "millionaire's tax." Last November they got their wish: Voters narrowly approved Question 1, amending the state constitution to impose a 9 percent income tax rate on all income over $1 million — a steep surtax over the flat 5 percent tax rate that previously applied to all income. People like me argued that this would be a bad move, not least because it would make Massachusetts even more unfriendly than it already is to business and property owners and would accelerate the exodus that has been draining people from the state.

Well, my side lost that campaign. Yet MassBudget and its allies keep insisting that steep taxes on the wealthy won't have any impact on the number of people leaving the state. In a report released last Thursday, the organization does its best to convince readers — or to convince itself? — that "High-Income Households are Not Fleeing Massachusetts." In fact, it claims, Massachusetts residents with high incomes are less likely to leave the state than low-income residents.

In reality, as the Pioneer Insitute found when it crunched recent IRS data, the overwhelming majority of net out-migration from Massachusetts, more than 80 percent, was among individuals earning over $100,000 — and 60 percent had incomes above $200,000. Of course people relocate for many reasons, most of which have nothing to do with taxes. But Massachusetts now ranks fourth among all states in the number of residents moving out, and two-thirds of them go to New Hampshire and Florida, both states with no income tax. That doesn't seem like a coincidence.

On the same day that MassBudget issued the latest reiteration of its claim that high taxes don't drive millionaires away, Khari Thompson reported for Boston.com that one reason Boston Celtics player Grant Williams is glad to be going to the Dallas Mavericks is the Bay State's new millionaire's tax. Once the surtax on income over $1 million was factored in, there was no contest between the $48 million he was offered by the Celtics and the $54 million the Mavericks put on the table. Even if the Celtics had matched the Mavericks' offer, Williams would have ended up losing a fortune. As he told Boston.com, "$54 million in Dallas is really like $58 million in Boston and $63 million in L.A."

Those of us for whom even $1 million of income is a wild fantasy aren't about to lose any sleep over the tax concerns of people who are paid tens of millions. But it isn't necessary to sympathize with their plight on a personal level to grasp that the impact on Massachusetts is substantial. Rich people can take their vast incomes and leave. No matter where he resides, Grant Williams will be getting a whopping paycheck. If he were to stay in Boston, a big slice of that paycheck would be going to the Commonwealth. When he goes, all the taxes he would have paid go with him.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Fresh graffiti is vandalism. Old graffiti is a tourist draw.

My first thought upon reading the recent story about the tourist who carved his and his girlfriend's names into a wall of Rome's Colosseum was that he should be smacked with a hefty fine and prison term, then banished permanently from the country. My second thought was that in a few hundred years tourists might be lining up to see his graffiti.

The tourist was recorded scratching "Ivan + Hayley 23" onto a brick of the nearly 2,000-year-old amphiteater. When another tourist indignantly asked him, "Are you serious, man?" he turned around and grinned. Italy's Culture Minister Gennaro Sangiuliano posted the video on Twitter with the comment: "I consider it very serious, unworthy, and a sign of great incivility that a tourist defaces one of the most famous places in the world."

Of course he's right. If a judge throws the book at the vandal, I doubt many people will object.

Then again, is graffiti vandalism?

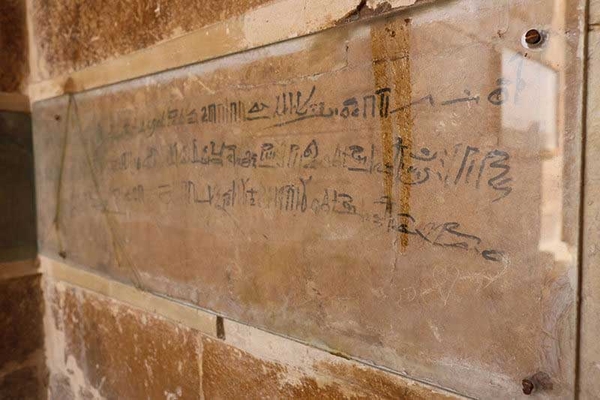

Graffiti scrawled 3,200 years ago by a tourist at the Saqqara pyramids in Egypt is now a protected cultural artifact in its own right. |

During a trip to Egypt in 1990, I visited the Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara, which dates from the reign of King Djoser in the 27th century BCE, making it even more ancient than the renowned Pyramids of Giza. A favorite memory of that visit is some lines of graffiti inscribed on one of the shaded interior walls of the building. Written 15 centuries after the pyramid was constructed, the graffiti was the work of a scribe from the court of Ramses II, usually identified with the pharaoh from the biblical Book of Exodus. "The scribe Ahmose, son of Iptah, came to see the temple of Djoser," he scrawled.

He found it as though heaven were within it, Ra shining in it. Then he said, "Let loaves, oxen, fowl, and all good and pure things fall to the ka of the deceased Djoser. May heaven rain fresh myrrh, may it drip incense!

Today, Ahmose's scribbled words of praise are protected by an acrylic covering and very much a venerated antiquity in their own right. But what were they when he daubed them onto the temple wall 3,200 years ago?

By the same token, what should we call the erotic boast — "Nikasitimos was here, mounting Timiona" — etched onto a rock outcropping on the Greek island of Astypalaia 26 centuries ago? Or the pair of phalluses added next to the words roughly 100 years later? What about the 2,000-year-old images of animals, including crocodiles, elephants, rhinoceroses, and baboons, scratched by visitors to the Musawwarat es-Sufra, a labyrinthine complex dating back to the kingdom of Kush in modern-day Sudan? How about the Arabic graffito left on a wall in Palmyra, Syria, a thousand years ago by a philosophical fellow named Musa the son of Imrawith: "This is an inscription that I wrote with my own hand," he recorded. "My hand will wear out, but the inscription will remain."

There is graffiti on the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey, thanks to schoolboys who carved their names there in the 18th century. "P. Abbott slept in this chair 5-6 July 1800," one youngster wrote irreverently. When Charles III sat in the chair as he was crowned this past May, those viewing on TV could easily see where P. Abbott and his pals had left their marks.

"Today we are used to thinking of graffiti as subversive or illegal, but ancient people didn't necessarily see graffiti in this way at all," the archaeologist Michael Press writes.

[S]cholars love ancient graffiti. Whether painted or inscribed, made quickly or over some time, these texts and drawings provide glimpses of a world otherwise largely invisible to us. . . . So much of what we know about the past comes from graffiti, from the earliest surviving examples of the alphabet (nearly 4,000-year-old graffiti at the site of Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai) to the earliest depiction of Jesus. . . .

But as much as archaeologists, heritage professionals, media outlets and governments love ancient graffiti, they seem to condemn modern graffiti at ancient sites just as much. . . . Heritage trusts in the UK call acts of graffiti "attacks" and are concerned that graffiti is "visually disturbing." Those responsible "should be ashamed." At best graffiti is "shocking" and "brazenly reckless"; at worst it is lumped in with terrorism.

In a 2020 blog post, historian William Youngs of Eastern Washington University pointed out that graffiti can be found in any number of national parks. Get caught scrawling on America's national treasures, and you can expect treatment comparable to what awaits that guy in Rome. But it wasn't always so.

At the Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, visitors' signatures covering the ceiling in the "Gothic Avenue" section of the cave are preserved and pointed out during guided tours. In the 1800s, visitors were encouraged to write their names on the walls of the underground labyrinth; among those who did so were Civil War soldiers serving in the Union Army.

Youngs similarly describes Pawnee Rock, a landmark on the Santa Fe Trail, where travelers traditionally carved their signatures. "A soldier on his way to the Mexican War complained, 'Pawnee Rock was covered with names carved by the men who had passed it. It was so full that I could find no place for mine.'"

Sometimes, ancient graffiti conveys deep emotional insight into the historical events of its time.

Many centuries ago, a verse from Isaiah — "You will see and your heart shall exult, and your bodies shall flourish like the grass" — was carved in Hebrew on one of the massive stone blocks that formed part of the wall at the foot of Jerusalem's Temple Mount. The carving was unearthed during the archeological excavations in the Old City after the 1967 Six Day War. The inscription appears to be an expression of joy by one of Jerusalem's beleaguered Jews at a development so wonderful as to seem the fulfillment of ancient prophecy. Some scholars think the words were written by a resident of the city during the reign of the 4th-century Roman Emperor Julian, who reversed his predecessors' antisemitic decrees, invited Jews to return to their historic capital, and — miracle of miracles — gave permission for the rebuilding of the Jewish Temple that had been destroyed by Vespasian nearly three centuries earlier. Sadly, that Jewish revival was extremely short-lived; it ended when Julian was murdered less than two years after his accession.

With age, graffiti is transformed from desecration to treasure. "If I find, one morning, 'John Scott 1990' cut into my gatepost, I am outraged," a letter-writer observed in the Times of London. "If round the other side I come upon 'Iohn Scot 1790,' I am delighted; and if under layers of paint I discover 'Iohan Scotus MCCCXC' I shall probably get a letter in The Times."

None of this is meant to let that numbskull at the Colosseum off the hook (or any of the others who have done the same thing). Scribbling on homes and taverns may have been an accepted form of commentary in ancient Pompeii, but the rules are different today. If you want to leave your mark in this world, don't do it on someone else's wall. Even if so many others have.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "A sure cure for 'Registry rage,'" July 13, 1998:

What in the name of Rube H. Goldberg is so complicated about renewing driver's licenses and automobile registrations? American Express and Visa renew tens of thousands of credit cards every day, cards that are worth real money, and nobody has to stand in line anywhere. This newspaper manages each morning to deposit a brand-new edition at your front door, and will continue to do so for as long as you wish, without ever requiring you to spend your lunch break dancing attendance on a surly clerk. Travel agents, insurance companies, overnight shippers — all of them are able to dispatch valuable documents by the millions, keep track of the records you want kept track of, and generally make themselves accessible to anyone with a telephone.

But when it comes to cars and driving, we have allowed ourselves to be conned into the belief that a government role is indispensable. And that that government role, alas, can only be performed ineptly, inconveniently, and in ill humor.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved." — Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species (1859)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.